Resident Doctors of the MGH, 1914-15. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.808

Introduction

As the MGH rounded the corner of its first centenary, it entered into a period of upheaval marked by two World Wars, a global economic depression, and the 1918 influenza pandemic. Despite major deficits, the MGH was at the forefront of innovations in medical research and care.

The outbreak of WWI saw large numbers of MGH staff volunteering for active duty abroad. Those who remained in Montreal continued to provide care to a growing population, including the first generation of veterans of modern warfare. Because of its affiliation with McGill, the MGH played a vital role in mobilizing the first university-led Canadian voluntary hospital, which in turn was responsible for groundbreaking research and advances in the field of combat medicine.

At the outbreak of WWI, citizens across Montreal began to volunteer as part of the Allied war effort. Those early MGH staff who volunteered for service joined forces with other medical practitioners from throughout the Dominion. Together they staffed field ambulances, casualty clearing stations, dressing units and hospitals near the Western Front in France and Belgium, as well as England, Egypt, Greece, and Turkey, as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. At home, despite shortages of supplies and staff, the MGH managed its daily operations and two additional wards for soldiers.

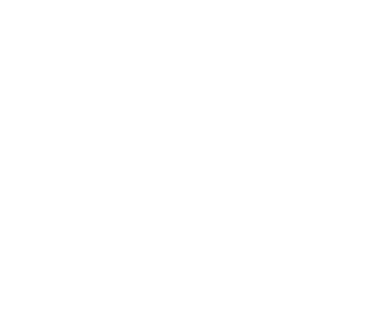

Letter from MGH Nursing Sister E. Frances Upton, from Salonica, Greece, 1916. Archives of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

No. 3 Canadian General Hospital: ‘The McGill Unit’

The largest portion of MGH staff served in the storied No. 3 Canadian General Hospital (CGH). The No. 3 CGH was established by Col. H.S. Birkett, a former MGH surgeon who was then the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at McGill. He was the first to volunteer a hospital on behalf of a Canadian university. Following the example set by McGill, other Canadian universities (including University of Toronto, Western, Dalhousie, University of Laval, and Queens) volunteered hospitals as well.

The No. 3 CGH was equipped with staff from the two McGill teaching hospitals, the MGH and the RVH. Birkett selected thirty-six nurses from each hospital to serve as Nursing Sisters – an officer’s rank for which they received military training in the McGill playing fields before deployment with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The hospital mobilized in March 1915, setting up a tent hospital at Dannes-Camiers near the Franco-Belgian border. By November they moved to a site in Boulogne and set up a hospital in the ruins of an old Jesuit college.

The No. 3 CGH is remembered for its contributions to trauma care and research on the effects of trench warfare and poison gas. Another MGH doctor, J.M. Elder, published a study showing that blood transfusions reduced the number of shock-related deaths. The combination of research and innovation produced an astoundingly low surgical mortality rate of less than 1%. By the end of the war, they had a reputation for being the best medical unit in the Allied Forces.

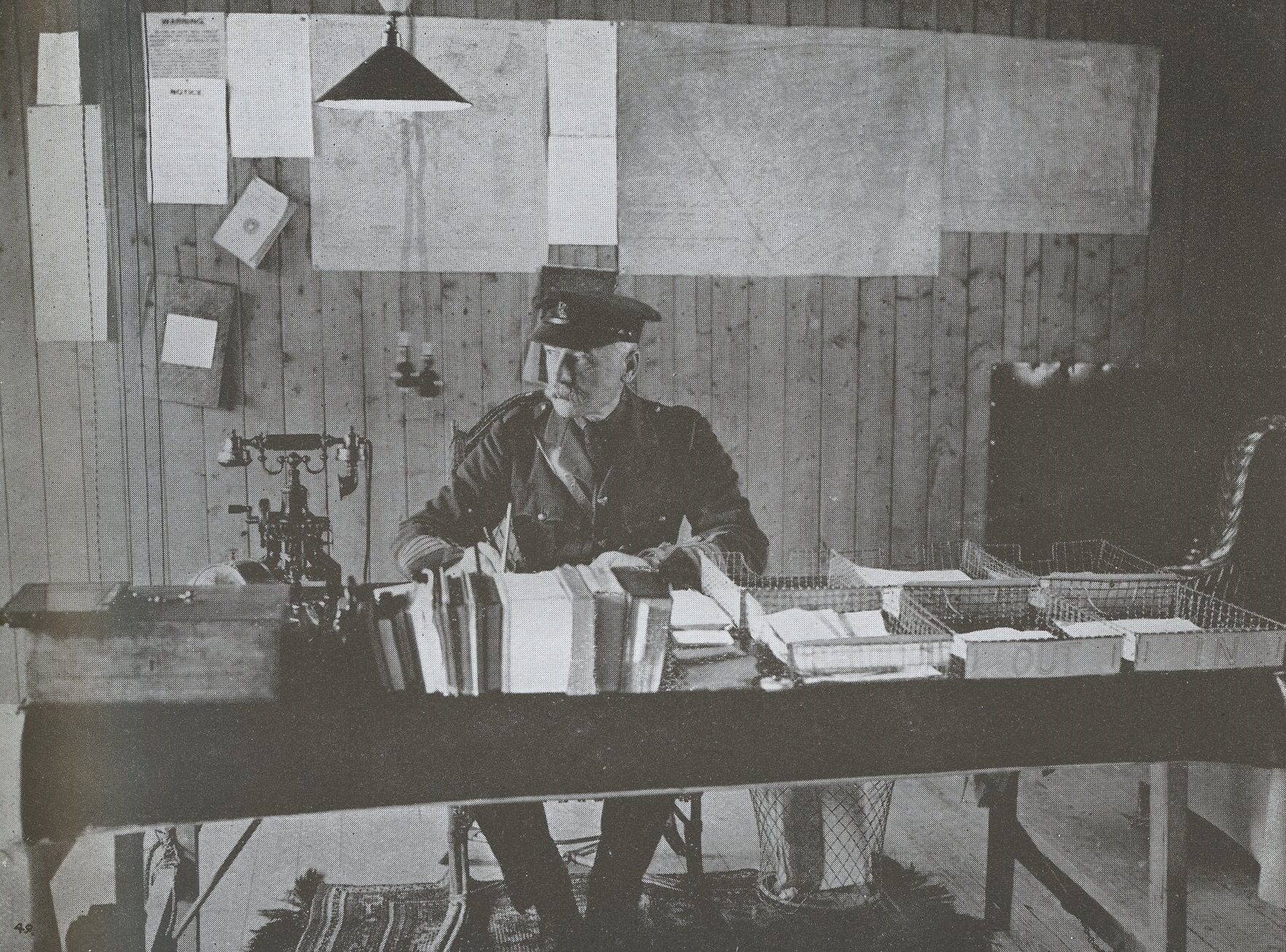

John McCrae: From MGH Pathologist to Fallen Soldier

John McCrae is best known as the author of “In Flanders Fields,” a poem that captured the widely-felt grief and loss specific to the war experience. McCrae was resident pathologist at the MGH from 1902-1904, a post he took up after serving as a lieutenant in the South African War. He went abroad with the Canadian Expeditionary Force to serve with the Canadian Field Artillery at the outbreak of WWI, where he treated soldiers wounded in the Second Battle of Ypres – a battle known for the Germans’ use of poisonous gas (the first such instance in the history of warfare).

After witnessing the death of his friend, McCrae wrote his famous poem. He then transferred briefly to the No. 3 CGH and was stationed there at the time of its publication. It was published in Punch and quickly gained popularity in the Commonwealth. McCrae died of pneumonia and other complications in 1918.

“The general impression in my mind is of a nightmare. We have been in the most bitter of fights. For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds … And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.” McCrae on the Second Battle of Ypres, in a letter addressed to his mother, reproduced in John F. Prescott’s In Flanders Fields: The Story of John McCrae, 1985.

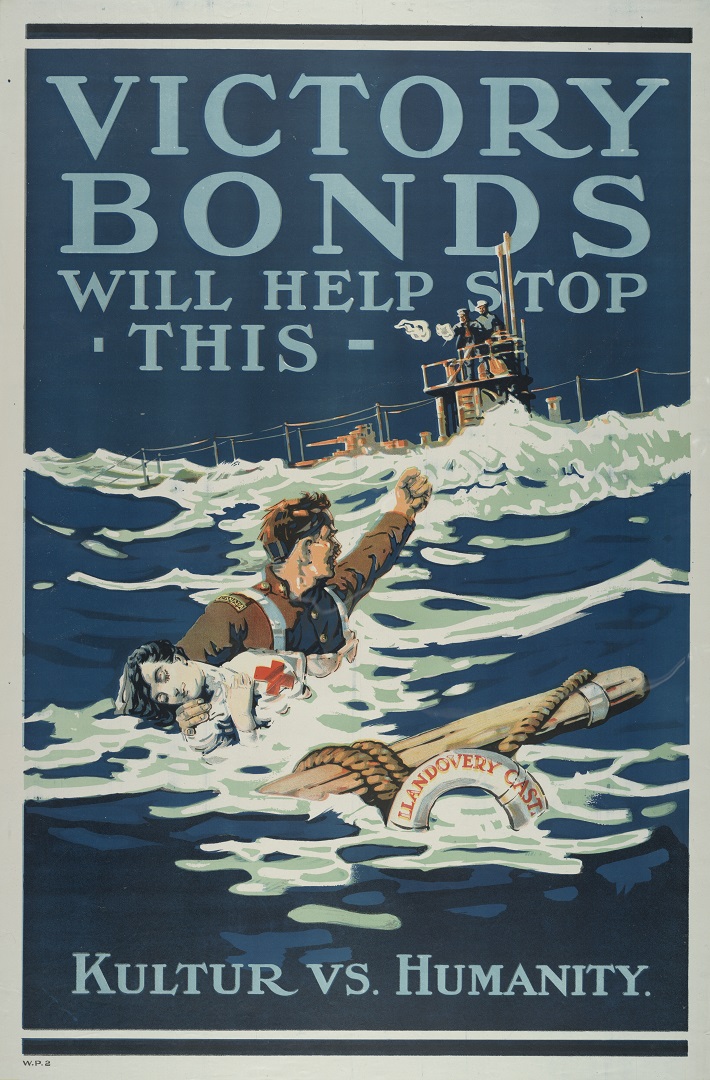

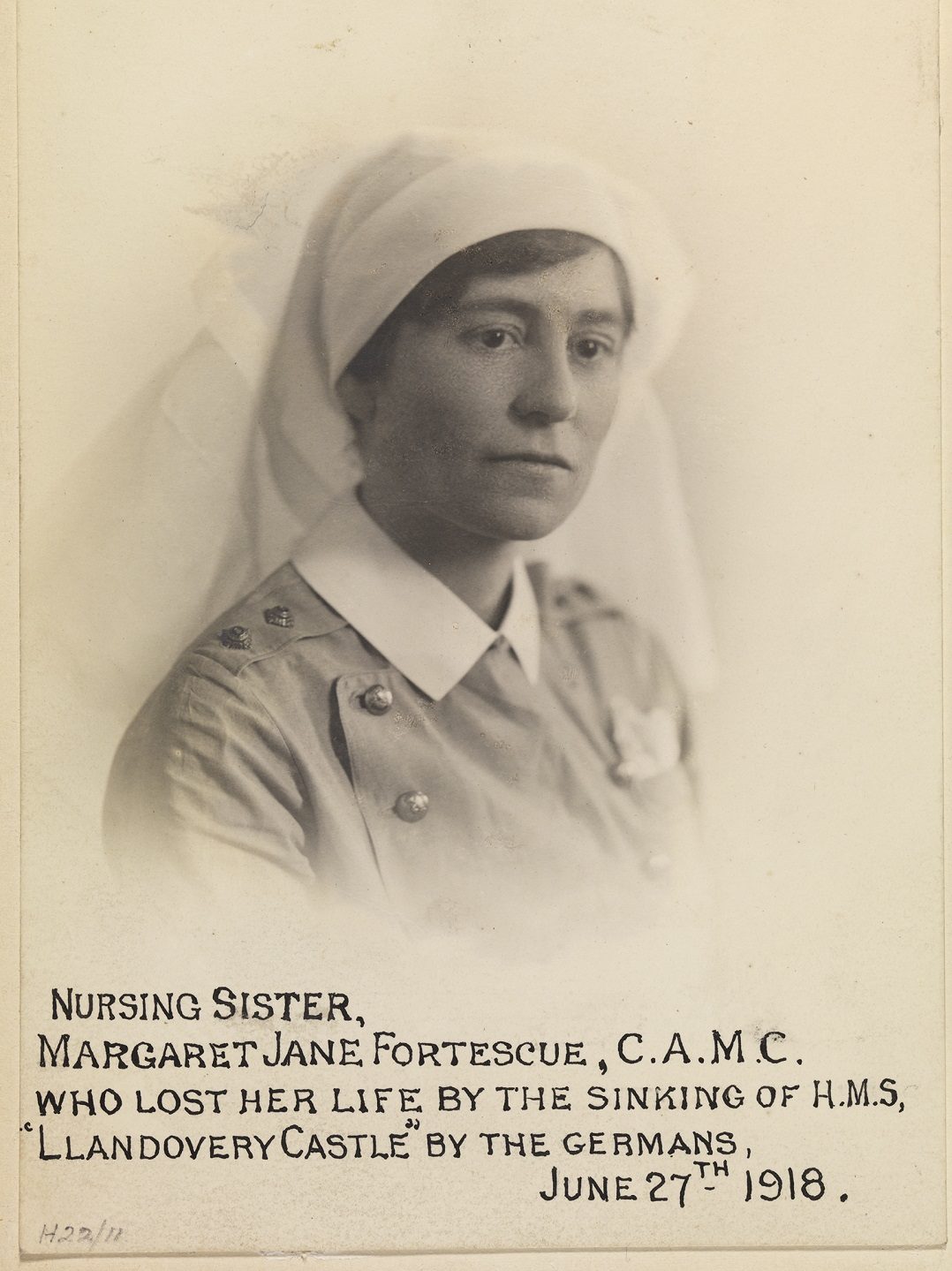

The Llandovery Castle Tragedy

On June 27, 1918, the HMHS Llandovery Castle – one of five Canadian hospital ships returning to England, having just discharged patients in Halifax – was torpedoed by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland. Only twenty-four passengers survived. Among those killed were two MGH nurses: Gladys Irene Sare (MGH 1913) and Margaret Jane Fortescue (MGH 1905). After the war, the German lieutenant and two of his men were convicted of war crimes during the Leipzig trials.

Interwar Period

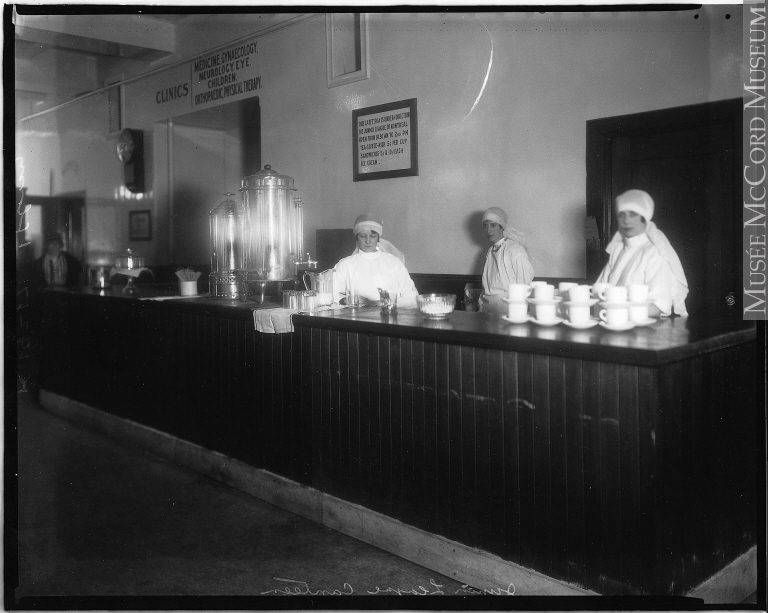

Junior League Canteen at the MGH, 1927. McCord Museum, VIEW-24217

With most of its staff returned from overseas, the hospital recovered from the shortages it had suffered during the war. Although it kept pace with the growth of the city and changes to medical practice, it had yet to secure substantial public funding and was operating under increasing deficits. The Great Depression compounded these troubles. This period also saw the introduction of large numbers of women into the healthcare workforce as a direct result of WWI.

Canada's Deadliest Pandemic: Influenza, 1918

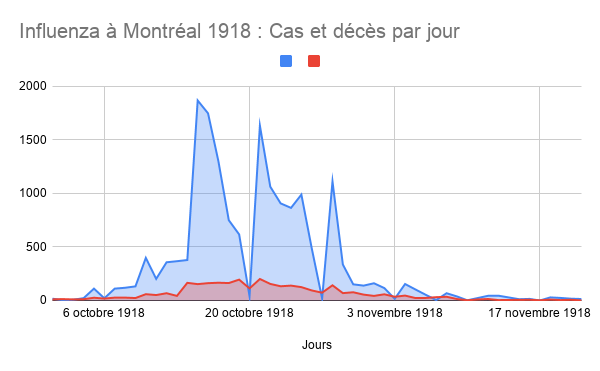

Chart showing daily numbers of cases and deaths in Montreal, October-November 1918. Although the initial spike in cases had died down in time for Armistice celebrations, subsequent waves brought at least another one thouusand cases and five hundred deaths to Montreal over the course of 1919-20, though cases are thought to have been underreported.

Marrio Robert, 2020. Influenza à Montréal 1918 – Cas et décès par jour, dans L’influenza de 1918-1919 à Montréal : « Le baromètre tragique ». Archives de Montréal.

Towards the end of the war, the deadly influenza pandemic of 1918, popularly known as the Spanish Flu, began its global conquest. The virus initially spread among soldiers, who were major vectors of the disease as they arrived in crowded military barracks from camps in the US. Montreal, a port city, was one of the first epicentres of the pandemic in the country, and the influenza spread into the general population from infected soldiers in the harbour. Montreal was particularly hard-hit during the fall of 1918, with a major spike in cases occurring in October.

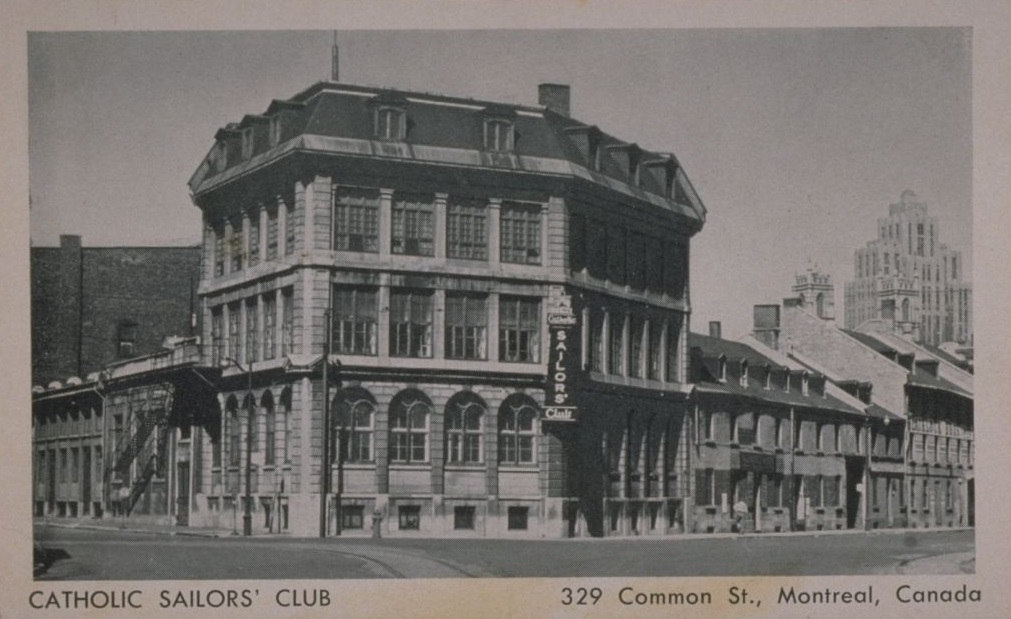

The pandemic exacerbated staff shortages that the MGH was already experiencing due to the war, as frontline staff themselves got infected with the flu and were forced to stay home. The annual report for this year notes that around thirty-five nurses were out sick on any given day, and registers 748 influenza cases and 144 deaths. With most civic hospitals overburdened, the MGH was also instrumental in advising and staffing a marine hospital set up in the Catholic Sailor’s Club to isolate infectious cases on ships docked in Montreal’s harbour.

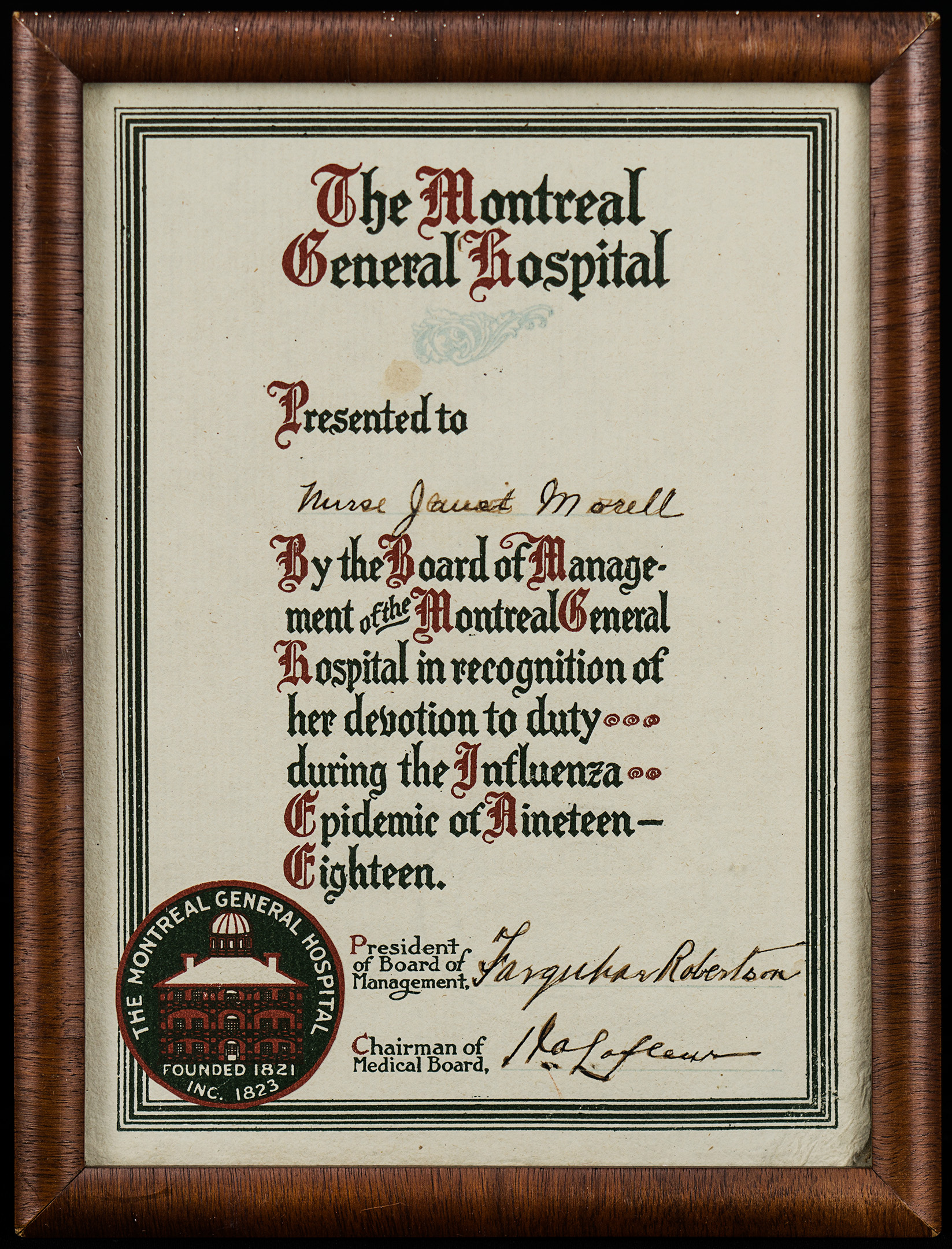

Nurses, nuns, and female volunteers played a key role in caring for the sick and dying and were recognized publicly for their efforts.

Certificate from the MGH presented to nurse Janet Morell for service during the 1918 influenza Pandemic. Archives of Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

The response on behalf of the city’s Board of Health emphasized closures and restrictions on public gatherings, but relied on an outdated conception of infectious disease: namely, that historic outbreaks originated among foreign populations that could be isolated in immigration sheds upon arrival. Because soldiers were not considered foreigners, little was done to limit the spread of the virus until it was too late.?

The pandemic led to the creation of the Federal Department of Public Health in 1919 and a corresponding shift in the discourse around infectious disease to better address its social causes. For example, higher mortality rates among densely populated, low-income households pointed to the importance of improving living conditions among those populations.

Overall, about three thousand people died of influenza in Montreal alone. The pandemic killed a total of over fifty thousand Canadians and, combined with the war, decimated an entire generation of young adults.

Economic Troubles

Since its inception, the MGH relied heavily on funds from private donors to operate, with little other than small annual grants from the government. Towards the end of WWI, under pressure from growing deficits, the MGH began to publicly implore the municipal government to better fund the city’s hospitals:

“It is absolutely wrong in principle that this and kindred institutions should have to depend almost entirely on the generosity of a few hundred citizens of Montreal. That was all very well a generation or two ago, when this City had a small population, but it is abundantly evident that this state of affairs cannot be continued. The burden has become too great, and we must now look to the civic authorities to provide for the support of the sick poor of the City who are treated in the hospitals, and who are unable to pay for this treatment. It is a civic duty which is recognized by practically every city of importance in the Dominion, with the exception of Montreal.” (Treasurer’s Report for the Year Ended 31st December, 1918.)

In 1921 the province established the Quebec Public Charities Act (QPCA), which acted as Quebec’s main public funding structure for healthcare until 1958. The QPCA involved a commitment from municipal and provincial governments to sponsor a portion of the cost of care for indigent patients. The provisions of the QPCA were inadequate for a number of reasons, however. Firstly, Quebec was the only province that refused to supply insulin, despite the MGH housing one of the largest diabetic clinics in the country. Secondly, the province refused to shoulder the cost of long-term care, the burden of which fell on individual hospitals and their social service departments. The QPCA also excluded costs related to migrants and homeless people.

By 1930 the hospital’s deficit was so pronounced that the city agreed to provide a grant of $25,000 a year for twenty years, just to defray interest costs. When the effects of the Great Depression hit, the hospital lost a vital source of revenue as patients who had once been able to afford private fees could no longer do so.

Western Hospital Merger

The Western Hospital had historically acted as the teaching hospital for Bishop’s University Medical School, a rival school that was amalgamated into McGill University in 1904. The hospital served a large population of private fee-paying patients, but it also routinely provided treatment for work accidents occurring in the industrial areas in the nearby Southwest.

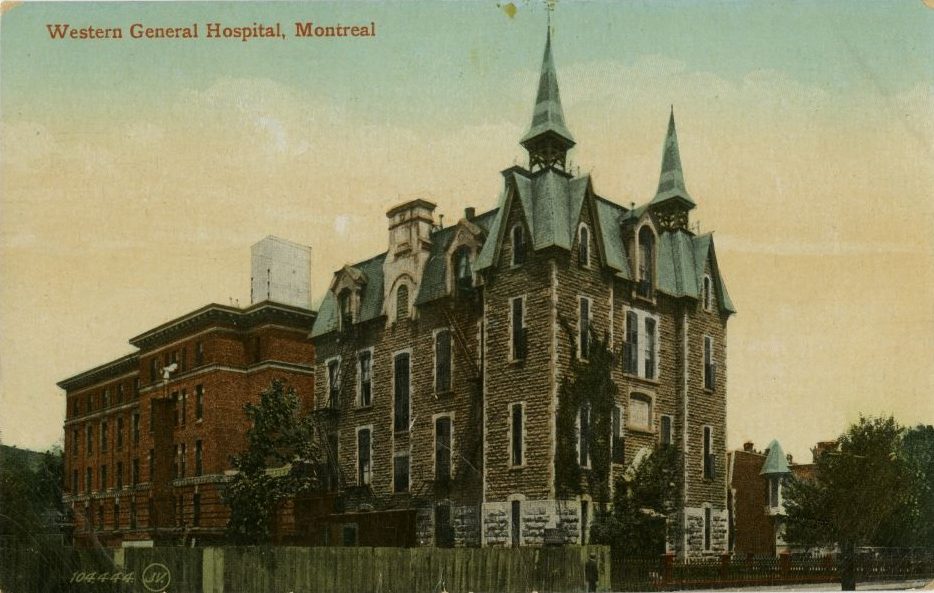

Western General Hospital, Montreal, showing the Mills building and Lyall wing, c. 1907-18. BAnQ, CP 030117 CON

In 1924, the Western Hospital, an institution that had opened in 1880 following the westward shift of the city’s English-speaking population, merged with the MGH. The transition happened following major deficits faced by both institutions in the years after the war. With the merger, The MGH would thus gain an important source of revenue in the Western’s private patient demographic, and in return the Western would be enfolded into the MGH’s long-established circle of subscribers – not to mention its reputation for clinical and medical expertise. The Western hospital, whose buildings then included the Mills’ building, the Lyall wing expansion, and a nurses’ residence, thus became the Western Division of the MGH.

By 1926, the MGH (which now included the Western Division and its deficits) and the Royal Victoria Hospital had a combined deficit of about 2.5 million dollars, precipitating a major fundraising campaign chaired by J.W. McConnell. By 1927 McConnell had personally canvassed his way into the hearts of some of Montreal’s wealthiest philanthropists, raising a total of about 4.7 million dollars (in 2020 dollars that number would be closer to 72 million). The MGH used a portion of their funds (which totaled roughly $2.5 million) to construct the Private Patient’s Pavilion of the Western Division.

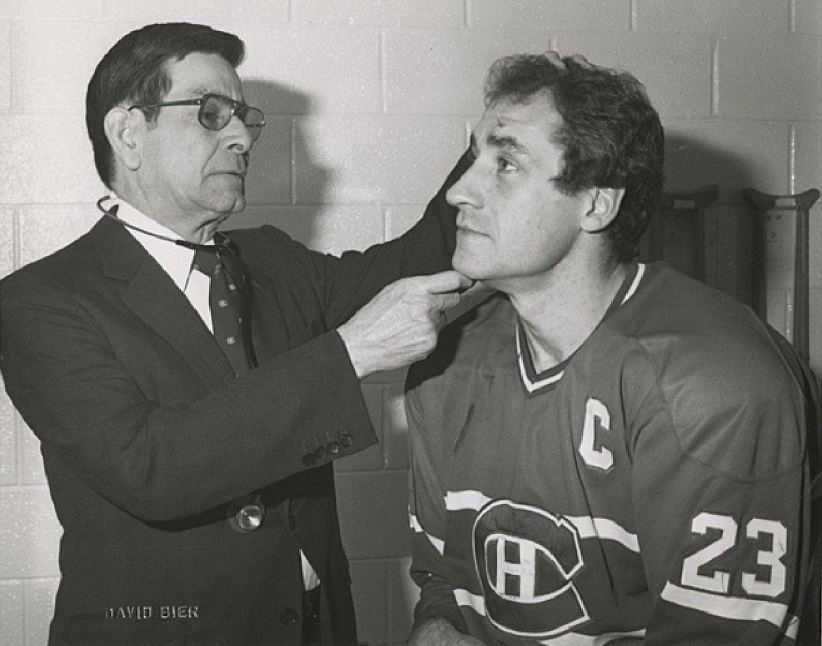

Proximity and necessity brought together the Western division of the MGH and the Montreal Canadiens Hockey Club, housed at the Forum around 1924. From then until today, many MGH physicians and surgeons have provided medical care to the players of this venerable Montreal sports franchise. Dr. Doug Kinnear and Dr. David Mulder have each served as team MD for over 30 years. The common thread between these two storied institutions is the Molson family, whose vision, generosity and service to the hospital are legendary.

Women in the Workforce

The general labour shortages during WWI and WWII created unprecedented work opportunities for certain women in Quebec. This larger shift towards emancipation would culminate in suffrage for Quebec women in 1940. During this period, women were able to take on new roles at the MGH that were previously exclusive to men, including the fields of medicine, research and laboratory work. On top of these new roles, positions that were already granted to women were able to expand with the creation of new paramedical careers.

The beginnings of clinical chemistry and laboratory-based research provided many opportunities for professional women. They would occupy many of the first lab technician and chemist posts in the Department of Metabolism in the years immediately following the war who, in addition to helping run the lab, performed investigative studies and aided in the preparation of research materials for publication. In 1919, the department hired its first dietician, Miss M.A. Perry, BSc.

Eleanor Percival

Obstetrics & Gynecology Clinic, 1938. L-R: Dr. Eleanor Percival (seated), Miss Irene Parker, Dr. K.T. MacFarlane, Dr. D.W. Sparling, Miss Jean Macrae, Dr. A.D. Campbell (seated), Dr. C.V. Ward. Art and Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Obstetrics and Gynecology Fonds, 2017.0003.04.13

The medical faculty at McGill University had refused to enroll women from its early beginnings. Despite repeated appeals for their inclusion, the faculty routinely rejected female applicants, forcing them to seek education elsewhere. During WWI, the faculty finally accepted its first female students.

Eleanor Percival was among the five women who were the first to be granted MDs in 1921, and she went on to become the first female physician at the MGH, working in the department of Gynecology. After her internship she was given an appointment at the Howard Kelly Hospital in Baltimore to study the use of radium to treat cervical cancer. She spent the following year at Johns Hopkins among the house staff of pioneering obstetrician John Whitridge Williams before returning to the MGH to run their radium program. She retired in 1959, when she was appointed honorary attending staff.

Hortense Douglas

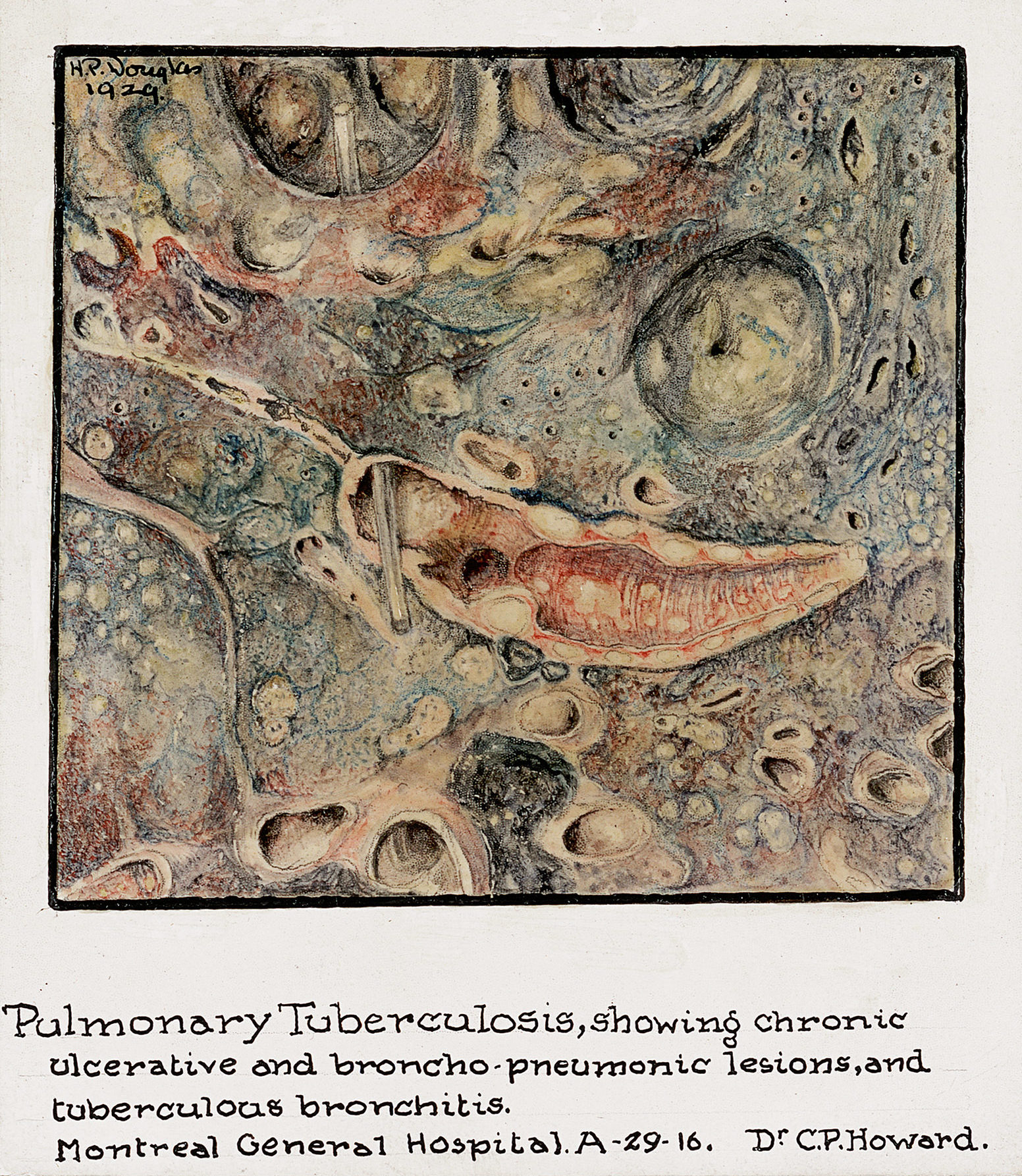

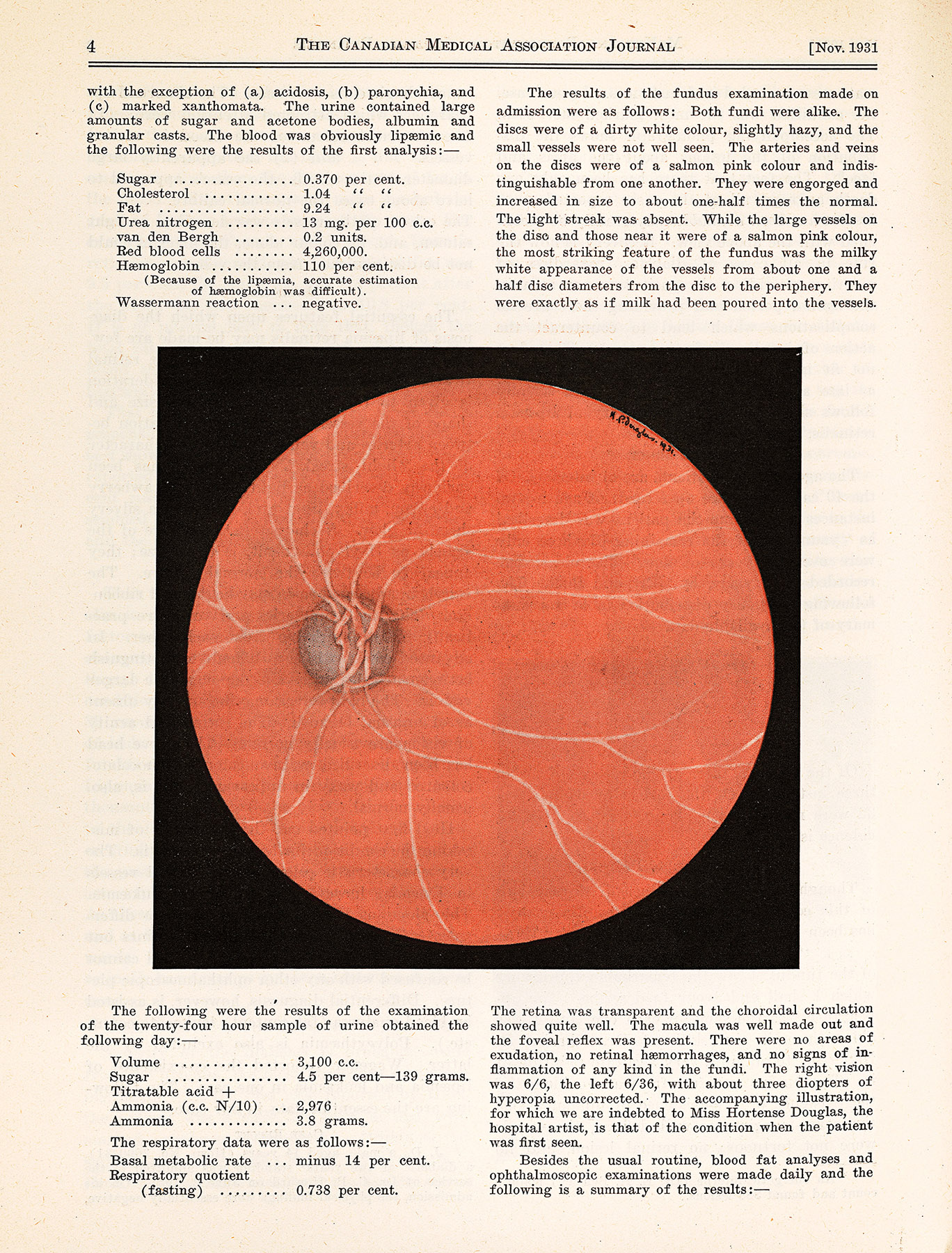

Douglas was born in Yonkers, NY in 1901 and moved to Montreal during childhood. She took art classes at the Art Association of Montreal in the early ’20s, and by 1923 was volunteering for the hospital as a Junior Leaguer. In 1924 she was formally hired by the department of pathology, and the following year the hospital sent her to Johns Hopkins University to study in the Medical Arts program.

Hortense Douglas, Mesenteric Thrombphlebitis, Portal Thrombosis with infarction of the jejunum and ileum, 1929. McGill University Archives, Hortense Pauline Douglas Cantlie Fonds.

Shortages at the hospital led to the involvement of many young women who volunteered their time. Among them, the Junior League became the prototype for a future generation of women’s auxiliaries, making valuable contributions to different aspects of hospital life. They used proceeds generated from the outpatient canteen to fund the social service department, operated a mobile library, and visited patients.

As a result of her volunteering activity with the Junior League, Hortense Douglas was given a paid position as medical illustrator (the hospital’s first) based on the drawings and watercolours she donated to the department of pathology.

Her work was frequently used as visual support for the pathology department’s clinical-pathological conferences, as well as to illustrate research published by MGH doctors. As the hospital’s first medical illustrator, her accomplishments were all-the-more remarkable considering the additional barriers presented by her deafness.

Allied-Health-Roles

Although openings existed before the war for women in social work, therapeutic massage, and pharmacy, the interwar years saw a flourishing of university-level paramedical specialty training. In 1918, McGill established the Department of Social Studies and Training; The School of Occupational Therapy would open in 1938; and the School of Physiotherapy shortly thereafter, in 1943. Students enrolled in these programs were given fieldwork opportunities, and eventually positions, at the MGH.

Nurses: Pioneering Professionals

As pioneering professional women, MGH nurses and nursing alumnae spent the decades following WWI continuing to participate in national organizations, both within the nursing world and in the broader movement for women’s suffrage in Quebec. Nursing Sisters who served in the war had earned the right to vote in federal elections with the Military Voters Act in 1917, but it wasn’t until 1940 that women in Quebec won the right to vote. The following year, influential Quebec feminist leader Therese Casgrain gave the keynote at the school’s graduation ceremony.

In 1932 the Canadian Nurses Association and the Canadian Medical Association jointly commissioned the Weir Report, the first comprehensive survey that addressed uneven standards of nursing education and examined nurses’ working lives, foreshadowing a series of documents and educational reforms that would culminate in the eventual closure of hospital nursing schools in the late 1960s. The Weir Report came with recommendations for schools to meet an elevated standard of nursing education, most of which the MGH already exceeded. One direct outcome for the MGH was the addition of a public health component to the nursing curriculum.

Students in the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing in a laboratory course, 1945. Archives of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

Further changes came to the Department of nursing following WWI, under the leadership of directors Sarah E. Young and Mabel Kathleen Holt. In 1920 the department hired its first specialist: a nurse anaesthetist, marking the beginning of new and increasingly specialized nursing roles at the hospital. In 1923 Young introduced student government, which promoted self-direction and organizing among pupils, and was also pivotal in the formation of the Association of Registered Nurses of the Province of Quebec (ARNPQ).

Medicine in the 1920s: The Father of Clinical Chemistry in Canada

In 1920 Israel Mordechai “Rab” Rabinowitch, a young MD fresh out of his internship at the MGH, established both the Department of Metabolism and the diabetes clinic at the hospital. Rabinowitch was one of the first people in the world to administer insulin, shortly after it was discovered (by Banting, Best, Macleod and Collip) in 1921. Rabinowitch was at the forefront of early diabetes research and care in North America: the clinic he directed out of the MGH was the largest in Canada for many years.

Rabinowitch outfitted the Department of Metabolism with a rudimentary biochemical laboratory, out of which the hospital’s first systematic research program operated. This was before the hospital itself recognized the value of routine lab work – Rabinowitch had to make his own lab supplies, or scavenge them from the diet kitchen – and his foresight made him a pioneer in clinical chemistry in the country.

World War II

In 1942, Blanche Herman was principal matron of the No. 14 CGH. On board the SS St Helena, they were torpedoed two days out of Gibraltar. Upon being rescued, they established a field hospital in an old tobacco factory in Italy, where she looked after patients from a variety of countries. Following her service and on her return, Holt appointed her nursing director of the Western Division.

Blanche J. Herman, Matron, no. 14 Canadian General Hospital, 1941. McGill University Archives, PL007185

When the Second World War broke out, the country had well-established training programs for its medical corps. MGH nurses formed the largest nursing group in Canada to mobilize for the war,? along with about 30% of the attending staff and many other hospital workers. At home, Central and Western divisions of the MGH dealt with major shortages in staffing as well as in food and equipment. The country’s research laboratories diverted their efforts toward combat-related investigations into shock, blood storage, and the treatment of traumatic injuries. These laboratories also began mass-producing antibiotics, toxoids and vaccines for infectious diseases that were threatening troops deployed in foreign campaigns.

Penicillin, discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, was mass-produced in laboratories across North America for use in WWII campaigns beginning in 1942, ushering in a new era for the treatment of bacterial infections using antibiotics.

Worker holds test-tube of penicillin in front of a bottle containing a surface culture penicillin mold at the Connaught Labs, 1944. Library and Archives Canada, National Film Board of Canada fonds, 3197454. Courtesy Harry Rowed/National Film Board of Canada

Chemical Warfare

In 1939, Rabinowitch travelled with Sir Frederick Banting to England to establish a liaison with the British Medical Research Council studying chemical warfare. By then, Rabinowitch had established himself as one of Canada’s foremost toxicologists, and became an authority on chemical warfare for the Canadian and British governments during WWII. After briefly returning home to present lectures to troops on chemical warfare and precautions against poison gas, Rabinowitch returned overseas to organize and command the No. 1 Chemical Warfare Defense Laboratory, while serving as General Andrew McNaughton’s advisor and personal physician. Rabinowitch was awarded the OBE in 1946 for his contributions to chemical warfare defense planning and research.

Nursing

Contributions

At the outbreak of WWII MGH nurses once again stepped up, registering for active service abroad and fundraising from home to support the war effort. MGH alumnae formed the largest group of Nursing Sisters serving in WWII out of all Canadian nursing schools. While 170 MGH nurses served in the war, at home, Miss Holt adapted the delivery of care to manage shortages by employing Voluntary Aid Detachment and practical nurses. In 1941, a group of nurses from the MGH Alumnae Association created the Spitfire Fund, which donated money to the Royal Canadian Air Force to purchase a fighter plane. The following year, they donated a mobile canteen to the Salvation Army.

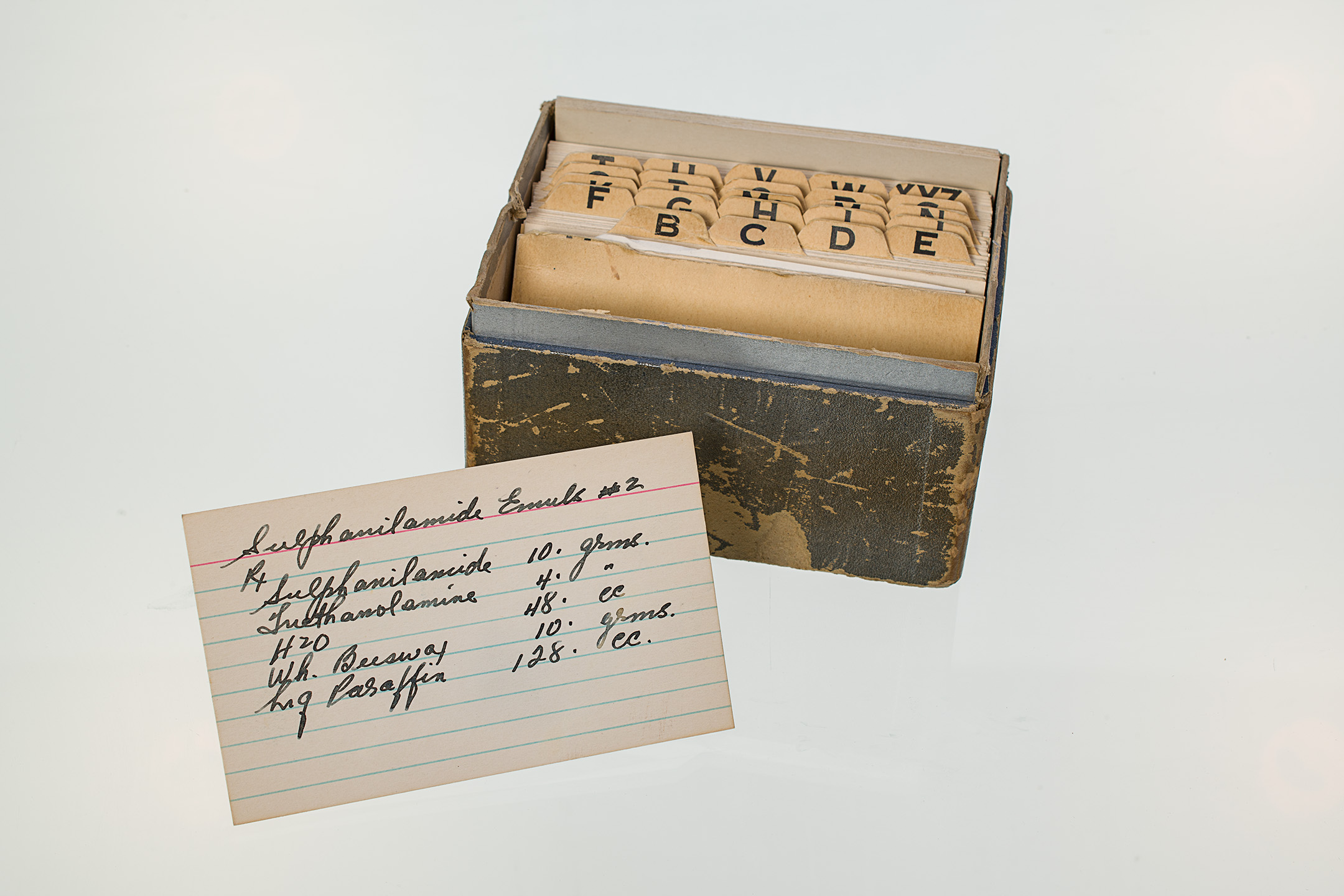

New Treatments

In 1942, MGH pharmacist Frank Zahalan teamed up with Fraser B. Gurd, F. Douglas Ackman, and Gordon Wilson to produce an emulsion to treat burns. The MGH Sulphathiazole Emulsion was picked up by hospitals throughout the continent and became the standard treatment for burns at Base Hospitals abroad, a major contribution to military medicine at the time. As a teaching tool, the hospital produced a film that was distributed to medical schools in Canada and the US.

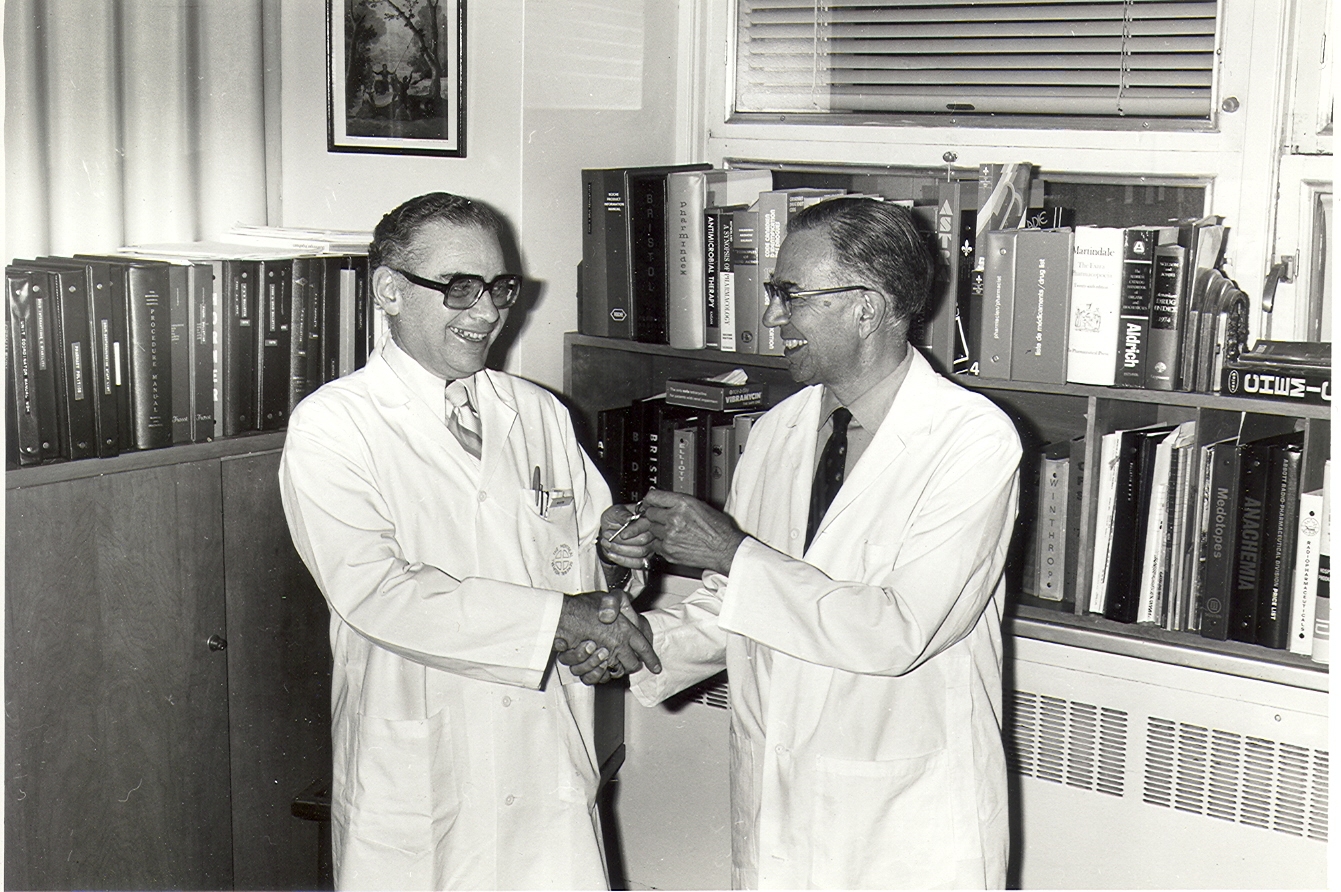

Frank Zahalan, right, pictured with MGH pharmacist Nathan Fox, c. 1970s. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.932

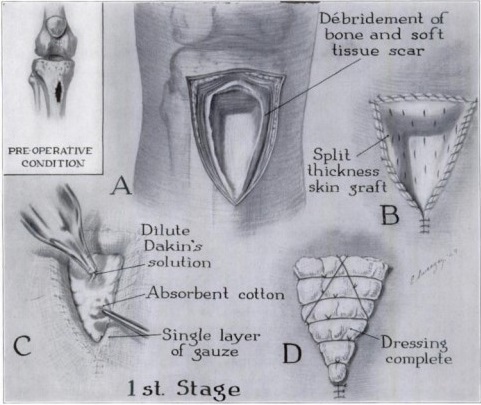

Eleanor Sweezey, Schematic drawing showing radical excision of bone and soft tissue and application of split-thickness skin graft. Used with permission from J.G. Shannon and F.M. Woolhouse, “Treatment of Chronic Bone Infection,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 36, no.4 (1954): 841-50

As a result of their wartime experiences, MGH surgeons J.G. Shannon and F.M. Woolhouse pioneered a method for the treatment of bone infections in compound fractures using a technique that involved removing (excising) infected tissue and applying an immediate split-thickness skin graft to the wound. This method improved outcomes of surgeries related to osteomyelitis in compound fractures, which were the site of frequent reinfections. This was particularly helpful in the management of gunshot wounds sustained during the war.

Experiences of Junior MDs

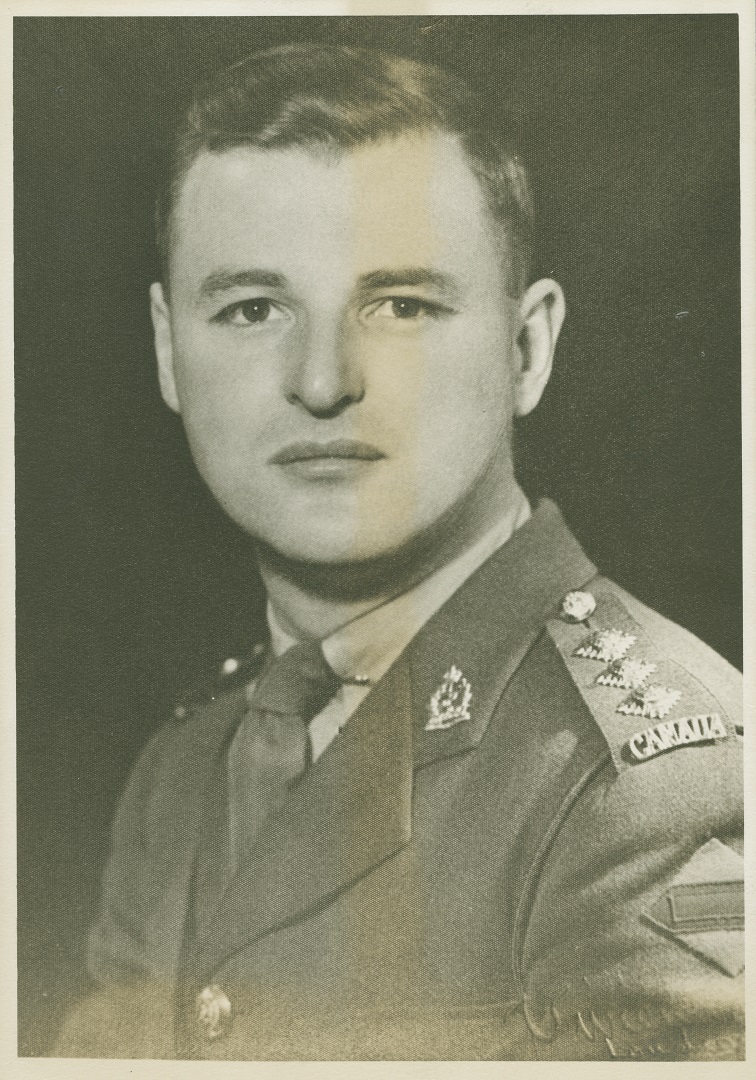

Dr. Harold Rocke Robertson, future MGH Surgeon-in-Chief, c. 1940s. McGill University Archives, PA044156

Junior physicians who served in the war gained vital experience, and ended up in bringing this experience to bear in leading positions at the MGH in the postwar years. This was especially true for young surgeons H. Rocke Robertson and Fraser N. Gurd (who served with his father, MGH surgeon and WWI veteran Fraser B. Gurd), who would go on to streamline the hospital’s emergency triage system. Robertson even overhauled the MGH’s emergency room to more closely resemble the receiving areas of the stationary hospitals set up in England during the war. These wartime experiences ultimately formed the basis of the MGH trauma service to come (and widespread reputation as the preferred destination for trauma cases in the city).