Ward M, Montreal General Hospital, 1904. Art and Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Mann Fonds, 2017-0001.04.1.33

INTRODUCTION

Painting of a harbour for Henry Sandham, Montreal, QC, 1880. Notman & Sandham. McCord Museum, II-56905.1

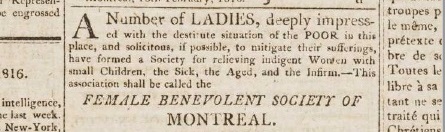

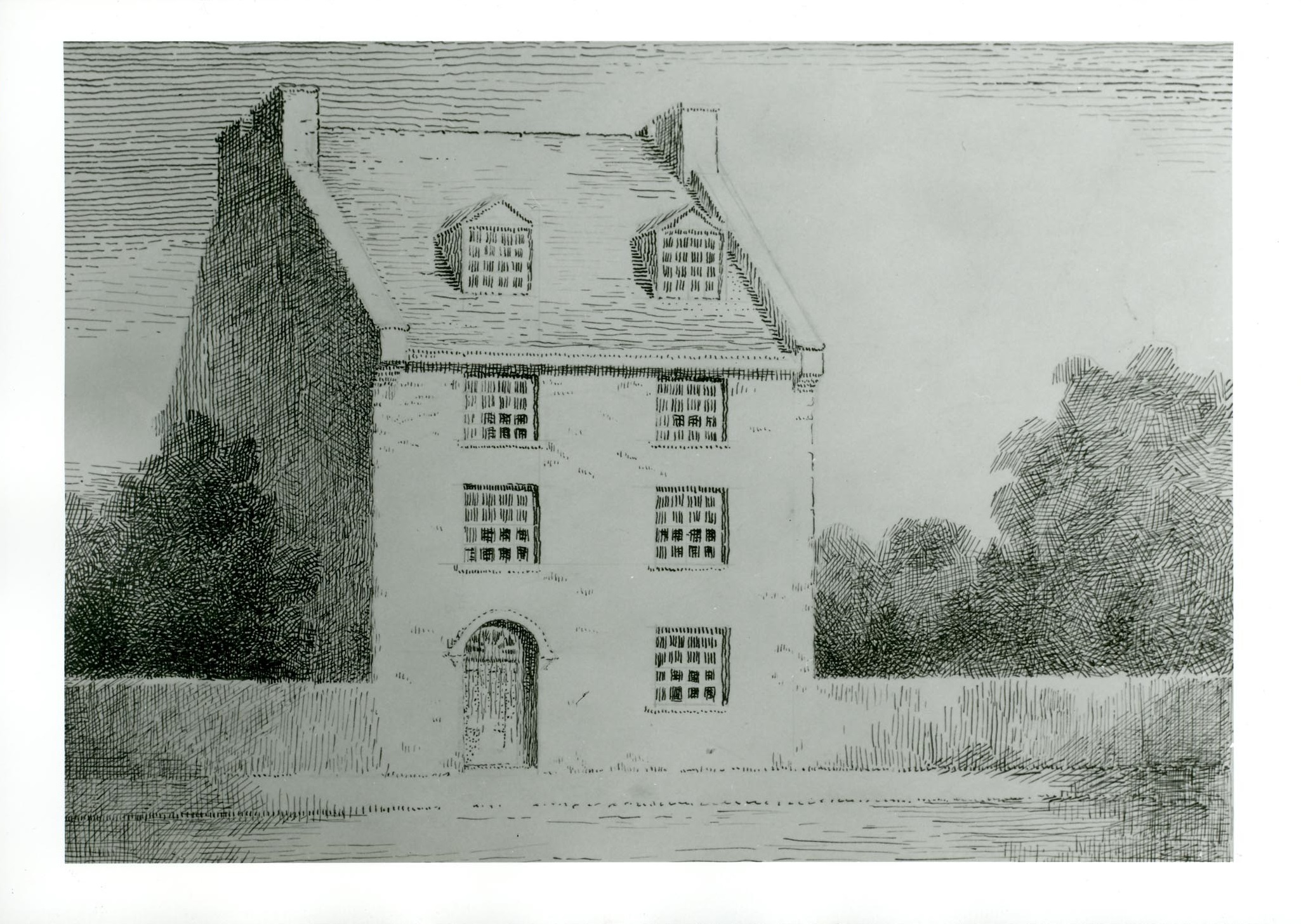

The Montreal General Hospital began as a community initiative driven by the Female Benevolent Society of Montreal, a charity formed by a group of Protestant women who recognized the urgent need for care on behalf of growing waves of indigent immigrants arriving in the city from across the Atlantic. The MGH was the first general public hospital open to all creeds to serve the needs of the Montreal community, and has remained faithful to this principle of service for over two centuries. Its unofficial first location was a modest, four-bed shelter opened in the Recollet suburb in 1818.

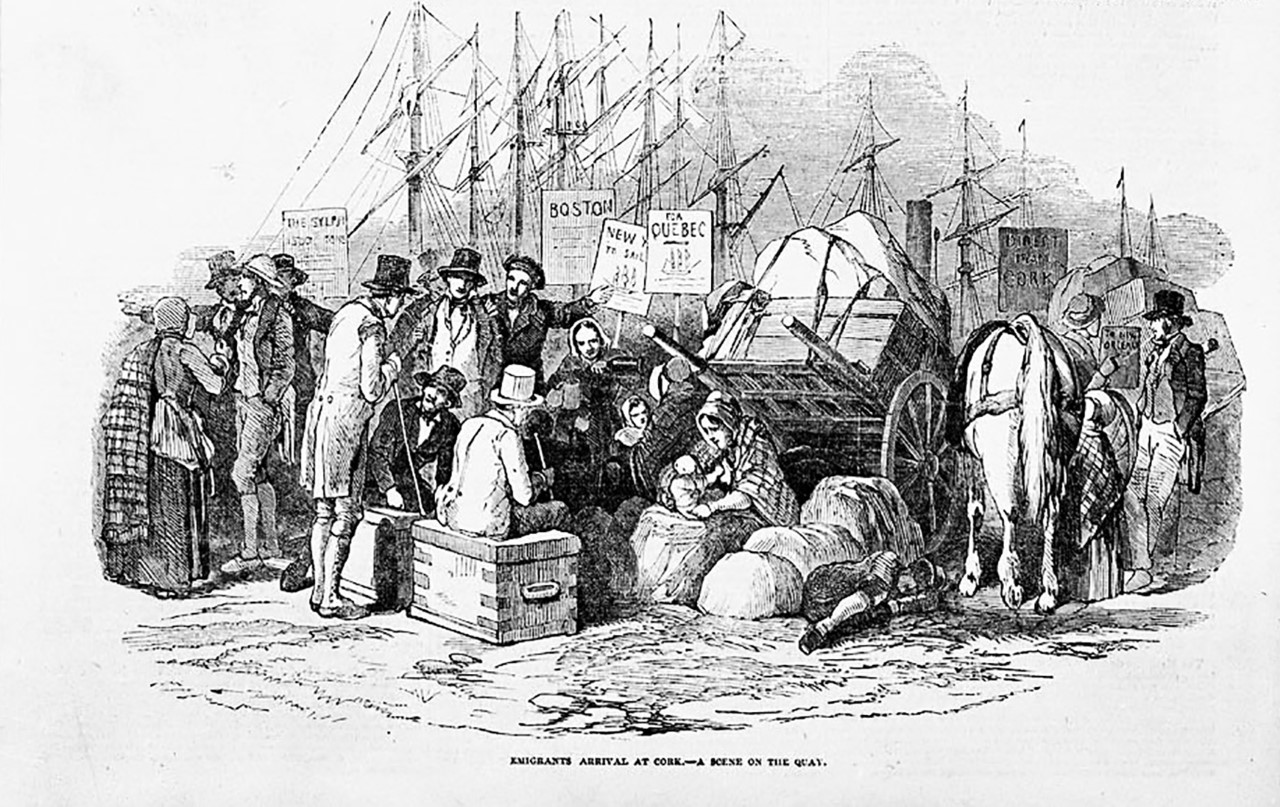

Located on the traditional unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá :ka Nation, Montreal’s settler population exploded in the first few decades of the 19th century, increasing from nine thousand to twenty-seven thousand inhabitants. In 1816, over five thousand people came to Montreal, mostly from the British Isles, settling in the southwest where they could obtain work in the nearby harbour. During this time, the majority of the population was British in origin for the first time in the city’s history.

The Napoleonic wars and their aftermath created two conditions favourable for the movement of newcomers to Montreal. One, changes in British trade after the war left vast amounts of people destitute, especially merchants and tenant farmers facing eviction in Ireland. Two, after 1815 the Atlantic became safe for unarmed ships, and many people came to Montreal seeking business and farming opportunities.

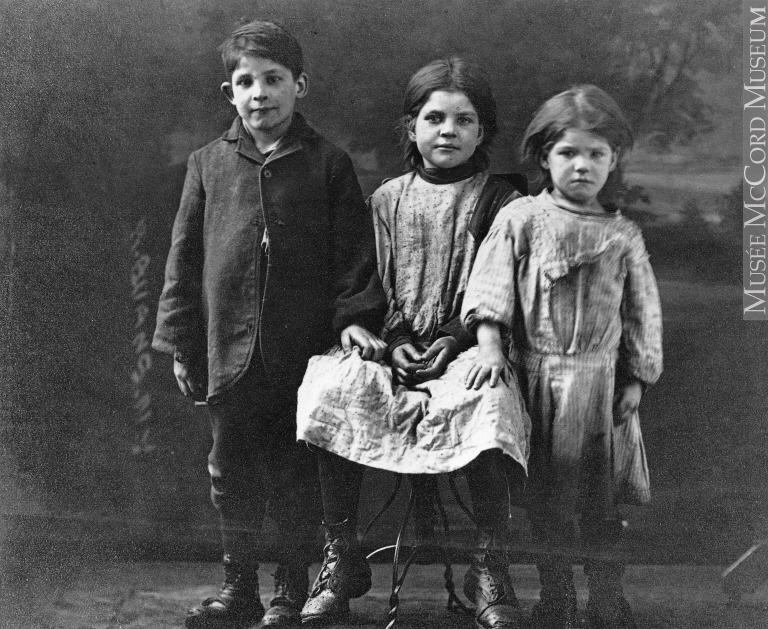

Goose Village children, Montreal, QC, about 1910. Art Studio. McCord Museum, Gift of Mr. John Stanley Kennedy, MP-1979.131.

MEDICAL CARE IN MONTREAL

IN THE 19TH CENTURY

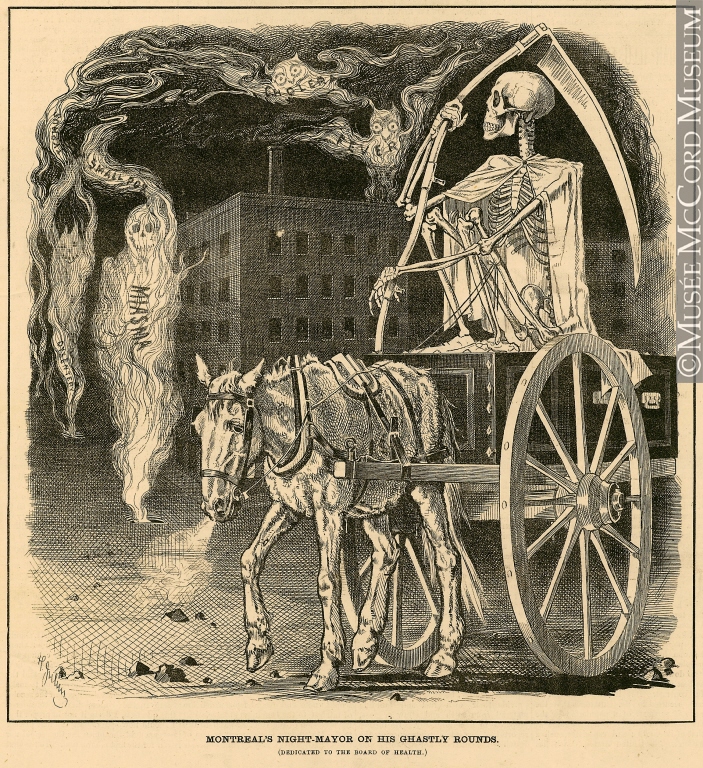

Montreal’s Night-Mayor on his Ghostly Rounds (Dedicated to the Board of Health), 1875. McCord Museum, M992X.5.82.

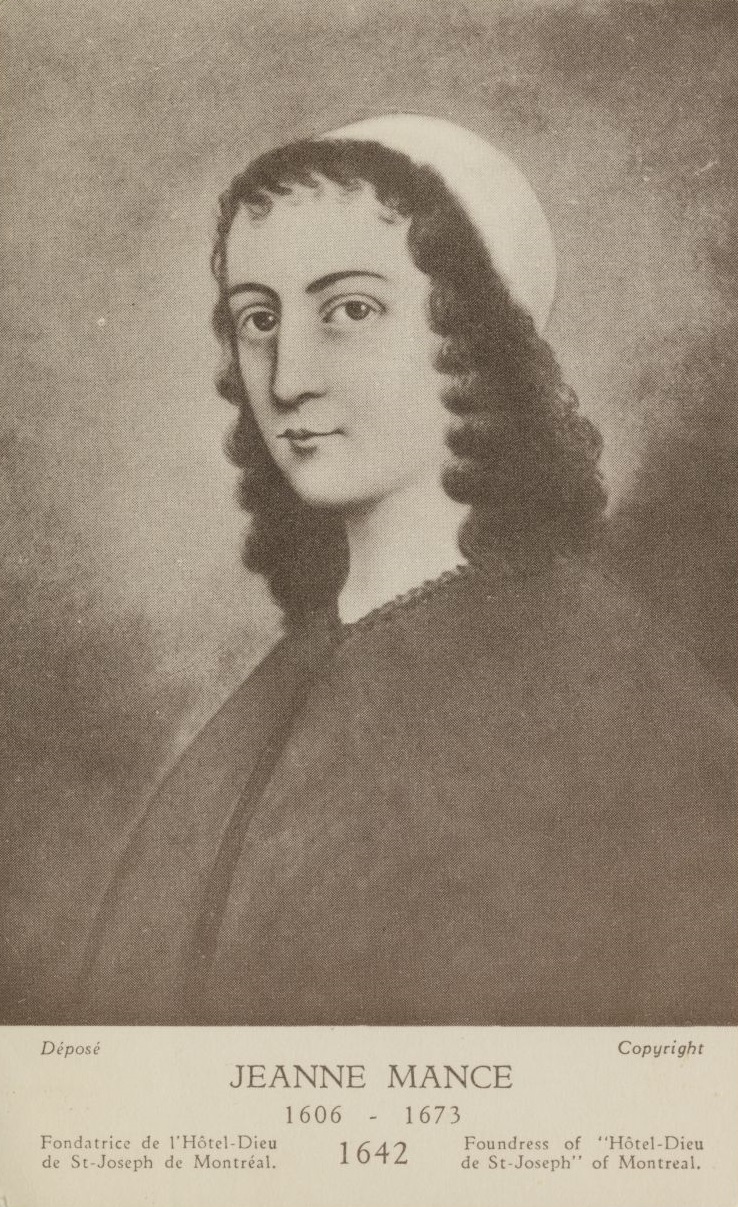

Prior to the creation of Lower Canada in 1791, Montreal was a small French colony with limited resources for medical care. In 1645, Jeanne Mance created Hôtel Dieu, Montreal’s first hospital. By the early 19th century, Hôtel Dieu was the only hospital serving Montreal’s citizens, and there were just twenty-one licensed physicians for a city of twenty thousand. Individual doctors would perform house calls, but there was no single institution operating with an inclusive open-door policy in the city that could cater to an increasingly English-speaking, Protestant population. The Montreal General Hospital changed this reality.

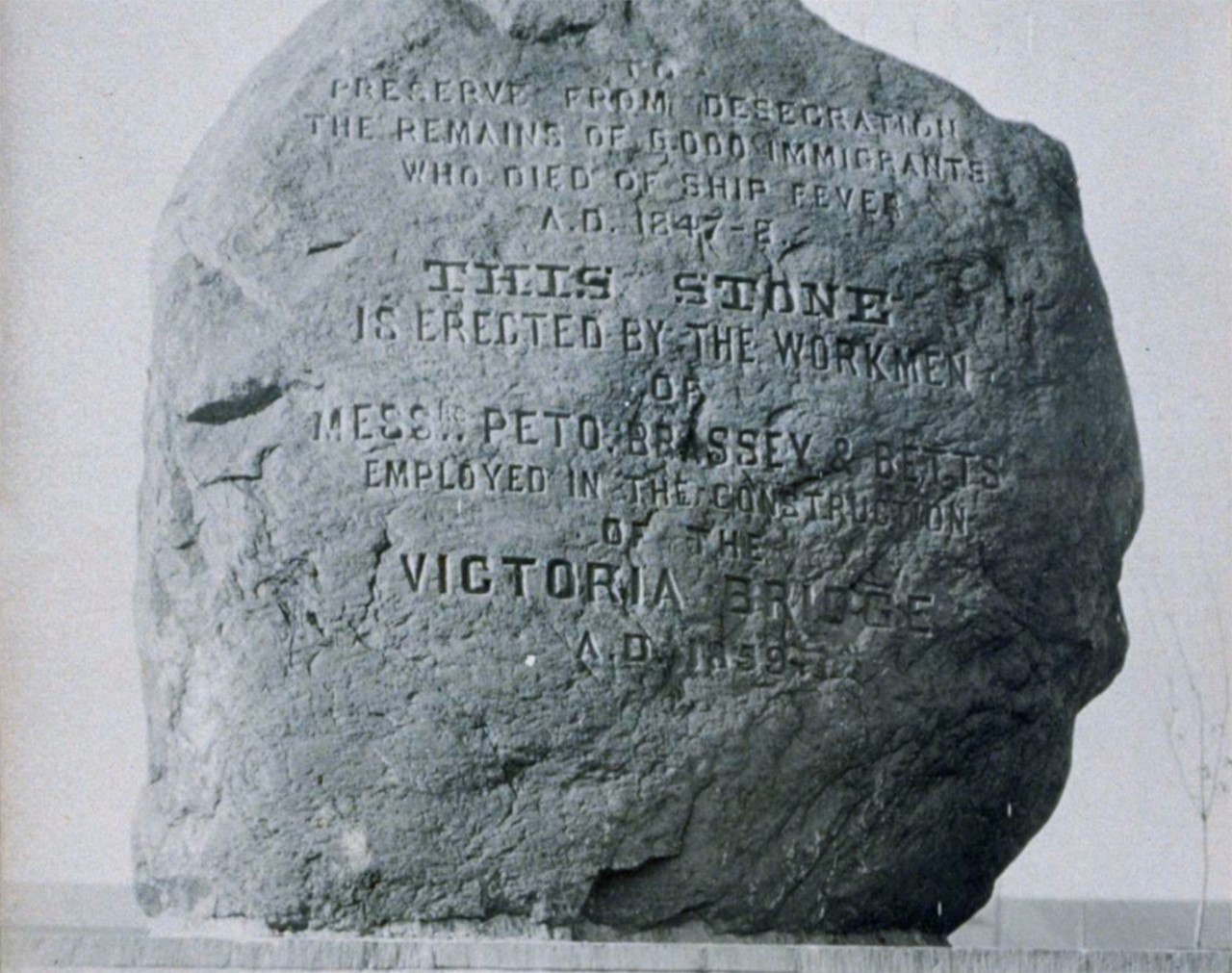

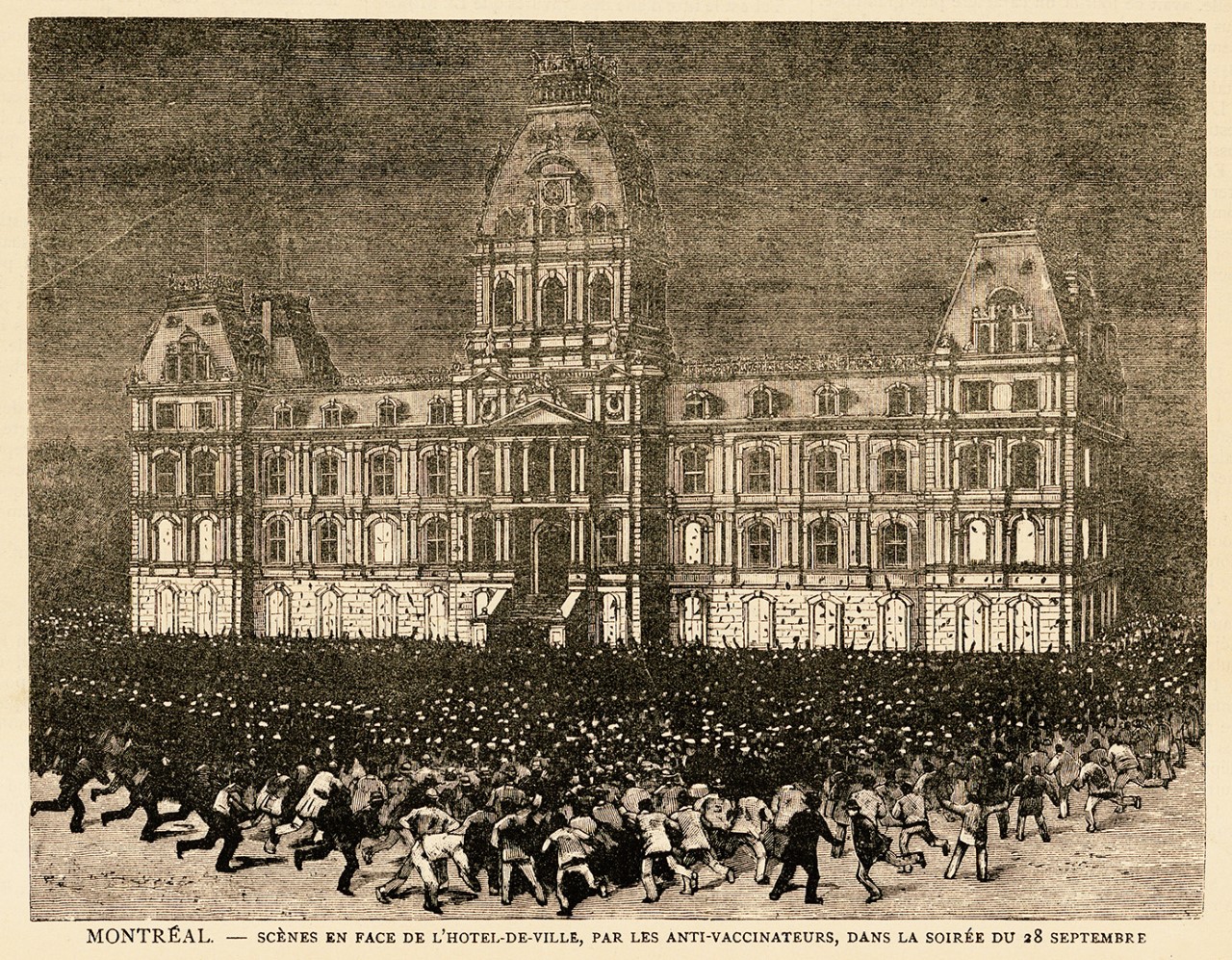

In the 19th century, medical care in hospitals was largely sought as a last resort. The majority of cases at the MGH were related to infectious diseases. The hospital developed an early reputation for treating infectious cases, and did yeoman service in the fever sheds in Goose Village during two of Montreal’s most severe epidemics: the cholera outbreak of 1832, which at its height claimed over six hundred lives in one week; and the typhus epidemic of 1847, whose six thousand victims were almost entirely Irish immigrants fleeing the Great Famine. This was before the days when the medical board of the city pursued systematic vaccination, itself the scene of a riot during the 1885 smallpox epidemic.

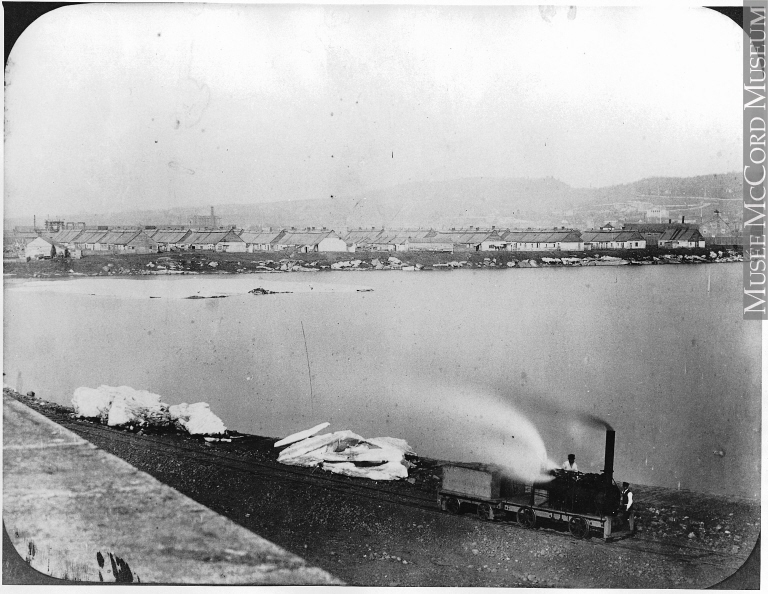

This image shows the fever sheds in the background that were converted to housing for labourers working on the construction of the Victoria Bridge.

William Notman, Construction buildings from top of bridge, Victoria Bridge, Montreal, QC, 1858-59. William Notman. McCord Museum, gift of Mrs. Henry W. Hill, N-0000.392.2.2

Extraordinary Beginnings

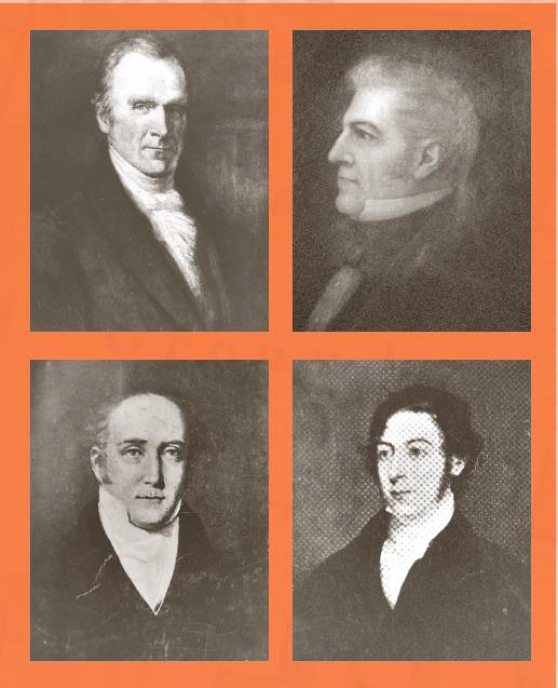

In 1819, John Molson Sr. delivered a petition to the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada requesting funds for the construction of a new hospital. At the assembly, politician Michael O’Sullivan argued that the healthcare needs of the growing population could be addressed by enlarging Hôtel-Dieu, and the request for funds was refused. O’Sullivan also suggested that the ‘advancement of the discipline’ called for in the petition implied carrying out experiments on patients. In fact, the petitioners wanted to open a medical school. This exchange led to a notorious duel between O’Sullivan and William Caldwell, one of the MGH’s founding physicians.

Many noteworthy members of the English-speaking mercantile class were proponents of the foundling institution, including John Molson, Sr. The early hospital operated in no small part thanks to the benevolence and volunteerism of its surrounding community.

19th Century Canadian School, Honourable John Molson (The Elder), c. 19th century. Collection of the Montreal General Hospital

The duel took place after an exchange in the April 10th edition of the Canadian Courant, a local newspaper. Dr. William Caldwell published an unsigned insult that targeted O’Sullivan, and the ensuing exchange led to one of the most notorious duels in Canadian history. The men met at 6am at Windmill Point, on the Southwest Montreal harbourfront. Each fired five shots, and while both survived their injuries, Caldwell was left with a shattered arm, and O’Sullivan with a bullet lodged in his spine.

Sketch of duel between Caldwell and O’Sullivan, nd, from Pages of History, edited by Jean C. Grout, 1981

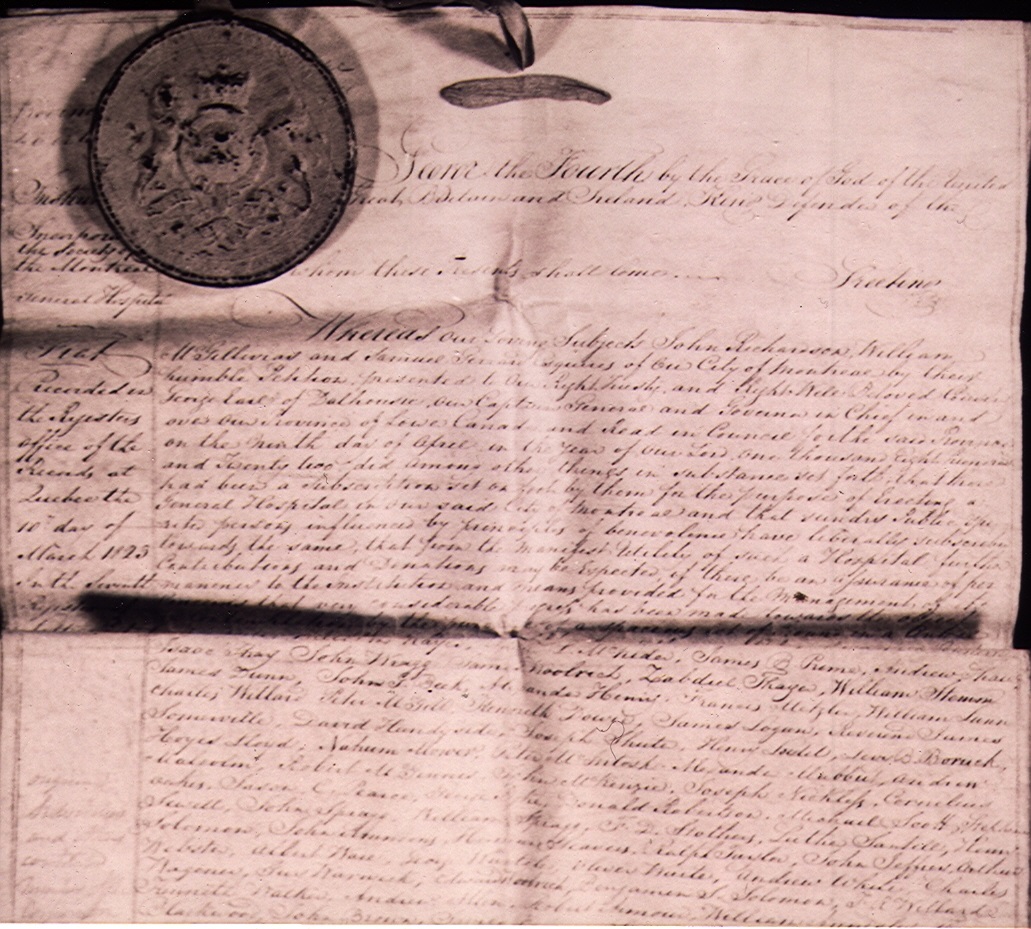

Though the petition failed to yield provincial support, the hospital’s founders were able to collect enough money from public subscription to open a temporary location on Craig Street. Meanwhile, land on Dorchester Street was purchased the following year, and a cornerstone ceremony was held in the summer of 1821, marking the official beginning of the MGH. The hospital was fully vindicated in 1823, when it received its Royal Charter.

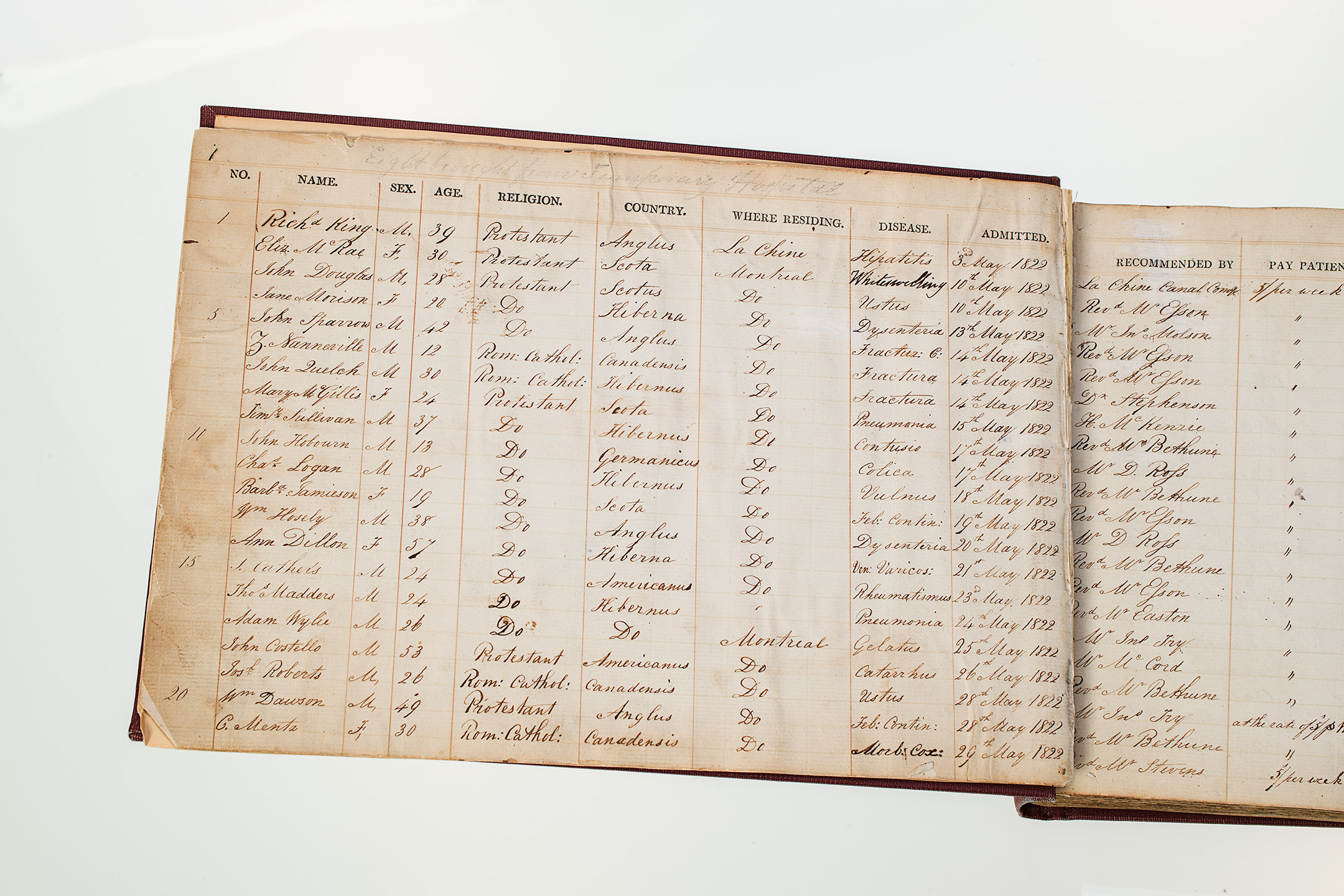

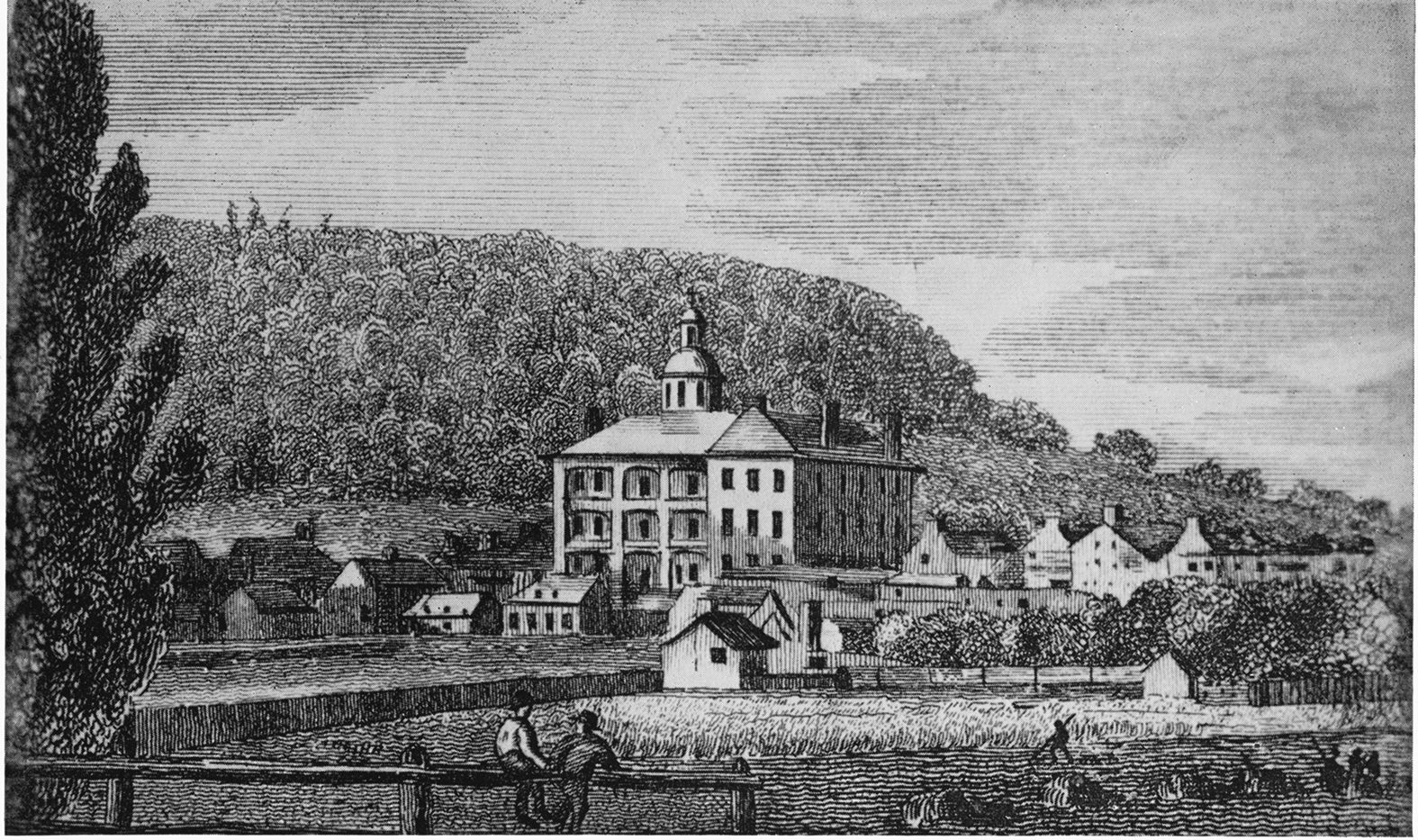

On May 3, 1822, staff and patients moved to the newly-built eighty bed hospital on Dorchester Street, designed by Thomas Phillips. The Richardson (1832) and Reid (1848) wings were added after to respond to ever increasing demand for beds.

A View of the hospital from the south showing the galleries, from Newton Bosworth’s Hochelaga Depicta, 1839. Reprinted in The Montreal General Hospital 1821-1956: A Pictorial Review, Special Number of the Montreal General Hospital Bulletin, Vol. 2, No. 8 (September 1956).

The Early Days of MGH Medicine

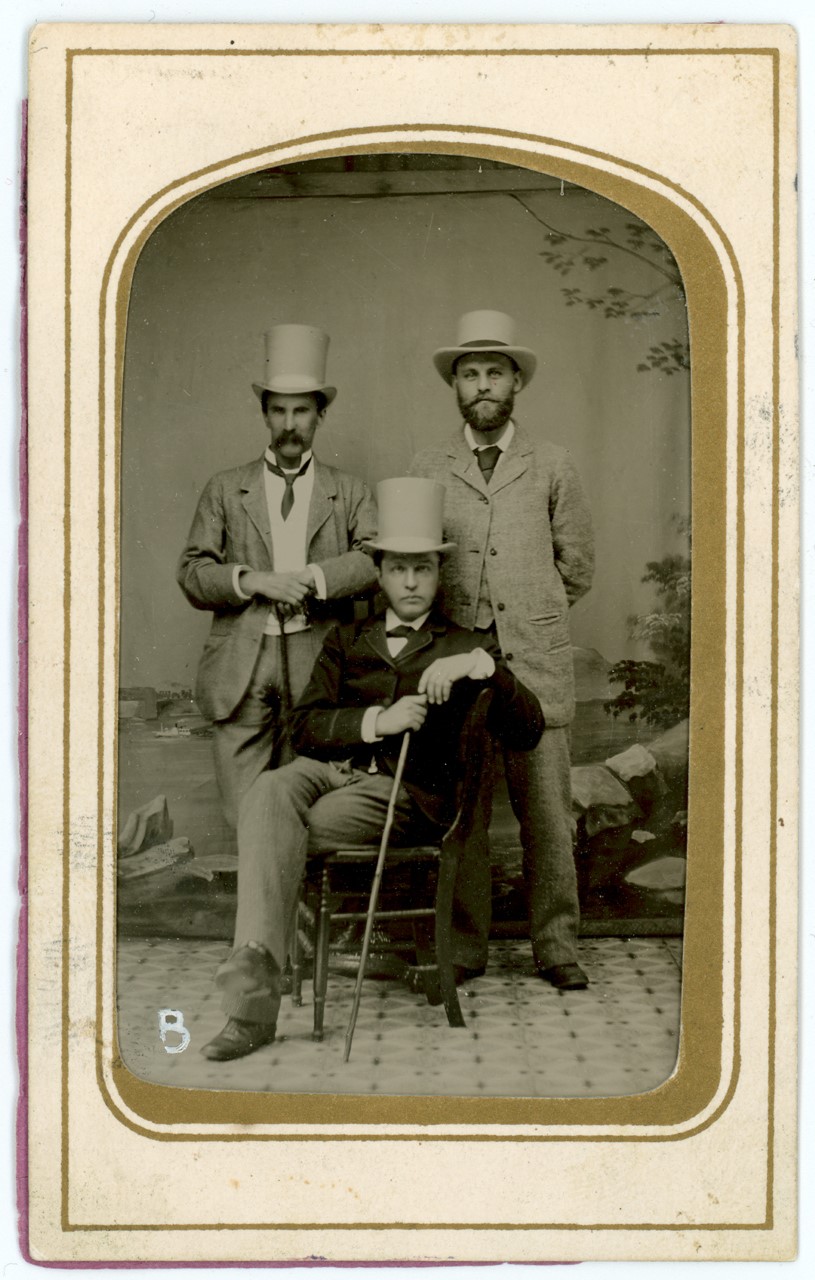

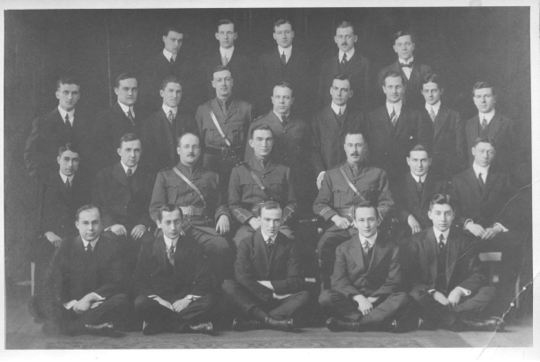

Resident Doctors group, Montreal, QC, copied 1895. Wm. Notman & Son. McCord Museum, II-110422.0

McGill University's Founding Faculty

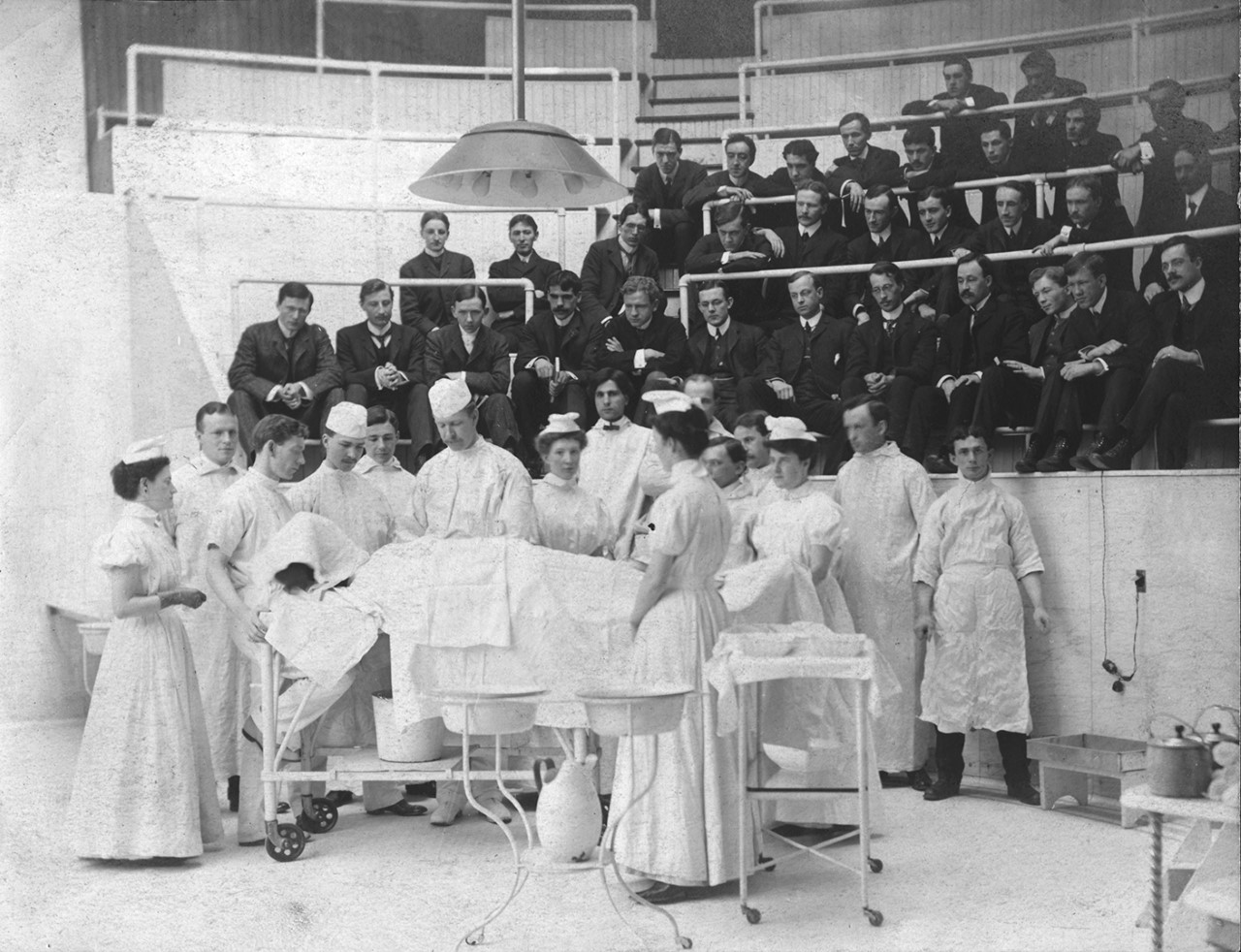

In 1822, the founding physicians of the MGH established the Montreal Medical Institution, modelled after schools in Europe that offered bedside teaching in addition to traditional lectures. When it was transferred to McGill in 1829, it became the university’s first faculty – and the first faculty of medicine in the country. With the creation of the medical school the hospital began to function as a teaching hospital, inaugurating the now-centuries-old relationship between McGill and the MGH. Scores of MGH physicians and surgeons over the years have been demonstrators, lecturers, departmental chairs and deans, overseeing the training of generations of medical students and residents.

L – R: Drs. Robert Palmer Howard, Thomas G. Roddick, George Ross, William Wright, William E. Scott, William Osler, John William Dawson, Francis J. Shepherd, William Gardner, George W. Campbell, Gilbert Prout Girdwood, Duncan C. MacCallum, Frank Buller, Robert Craik, Richard L. MacDonell, and George E. Fenwick.

Composite of 16 Scholars, medical faculty members, 1882. Osler Library, William Osler Photo Collection, CUS_033-011_P

The opportunity for hands-on, clinical teaching at the MGH is what drew the young Sir William Osler to McGill. Osler was particularly fond of the teaching style of Robert Palmer Howard, of which he wrote: “With him the study and the teaching of medicine were an absorbing passion, the ardour of which neither the incessant and ever-increasing demands upon his time nor the growing years could quench. When I first, as a senior student, came into intimate contact with him in the summer of 1871, the problem of tuberculosis was under discussion, stirred up by the epoch-making work of Villemin and the radical views of Niemeyer. Every lung lesion at the Montreal General Hospital had to be shown to him, and I got my first-hand introduction to Laennec, to Graves, and to Stokes, and became familiar with their works. No matter what the hour, and it usually was after 10 p.m., I was welcome with my bag, and if Wilks and Moxon, Virchow, or Rokitanski gave us no help, there were the Transactions of the Pathological Society and the big Dictionnaire of Dechambre. An ideal teacher because a student, ever alert to the new problems, an indomitable energy enabled him in the midst of an exacting practice to maintain an ardent enthusiasm, still to keep bright the fires which he had lighted in his youth.”

-Sir William Osler, “The Student Life,” Aequanimitas, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., 1914), 440-41.

Robert Harris portrait of Dr. Robert Palmer Howard at the bedside, 1889

Early 19th century

medical care

Before the discovery and systematic study of microbes by Louis Pasteur in the late 1800s, little was known about the origin of disease. Medical treatment was limited to medications such as digitalis, morphine, alcohol and nostrums, minor procedures such as bleedings and cuppings, and the occasional surgery. There was no ambulance system, and childbirth typically took place at home with the help of midwives. Surgery before knowledge of antisepsis was extremely risky and was considered only as a last resort. Prior to 1847, when the hospital started using ether and chloroform, patients were conscious during surgery. Nurses weren’t differentiated from servants on the payroll until 1859, and there was no system for training them until the arrival of Nora Livingston in 1890.

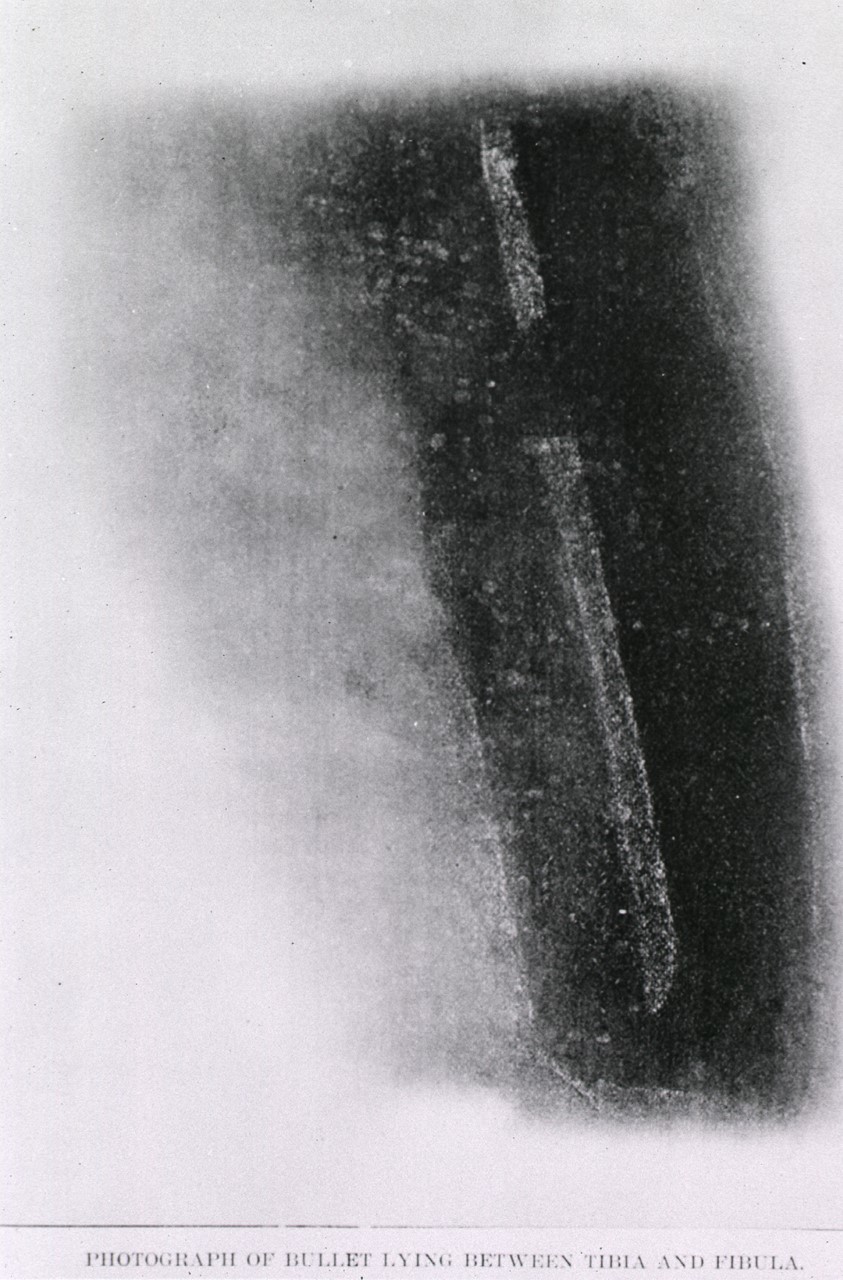

In February 1896, scarcely a month after German physicists Wilhelm Röntgen first demonstrated the use of the X-Ray, Dr. R.C. Kirkpatrick, an MGH surgeon, asked McGill physicist John Cox if he would take a radiographic image of a gunshot wound. The resulting image of the patient’s tibia allowed for its successful removal by Kirkpatrick, and the result was widely publicized as the first diagnostic use of X-Ray technology on the continent.

Photograph of bullet lying between tibia and fibula [of Mr. Talson Cunning]. [W.C. Macdonald Physics Building, McGill University, Montreal, Que., 7 February 1896.]. Library and Archives Canada, PA-122908.

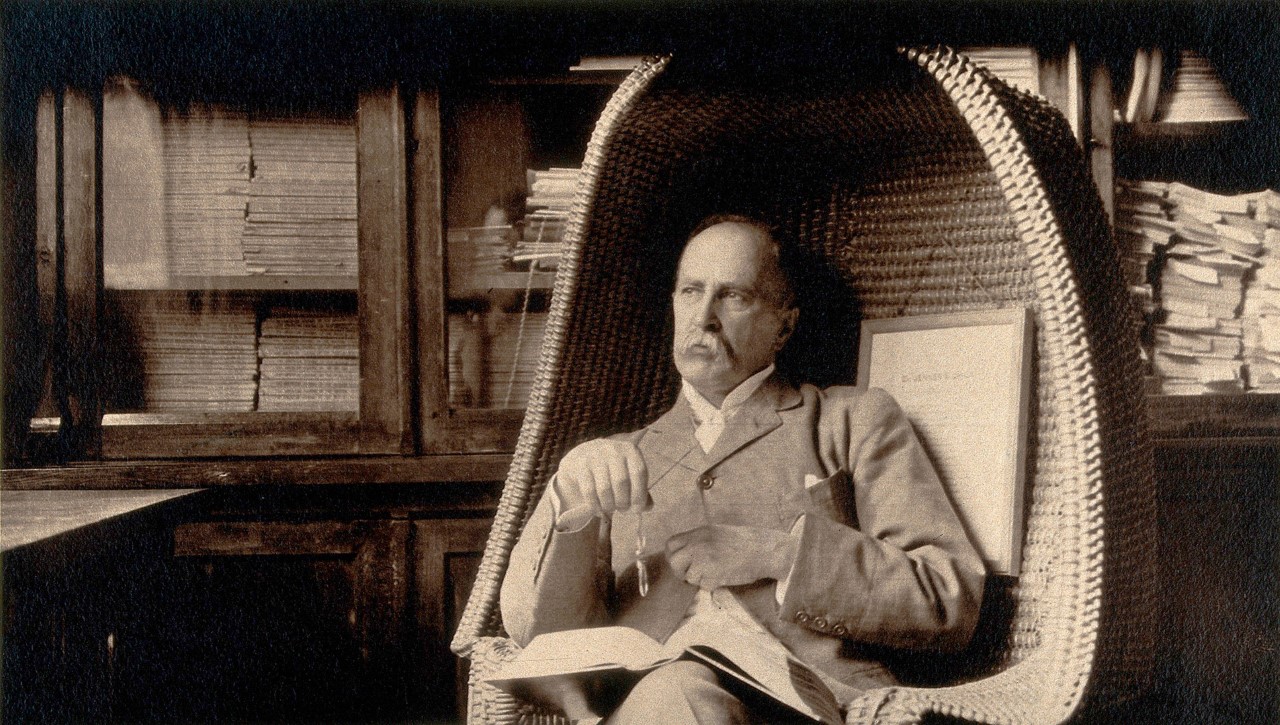

Sir William Osler and the Foundations of Teaching

Sir William Osler, one of the world’s most influential physicians, began his career in medical teaching in Montreal in 1874, shortly after graduating from McGill University. While a member of the McGill Medical faculty, Osler held various positions at the Montreal General Hospital which led to notable improvements: as physician, common-sense innovations on his ward led to better patient outcomes. As a clinician, he was responsible for the hospital’s first published reports, which became a staple and foreshadowed the MGH’s future role as a leader in medical research in the country. His early focus on observation as a diagnostic method would become the foundational principle of modern medical teaching in the Western world.

Osler’s work at the MGH laid the foundation for a brilliant career in medicine, which included positions as one of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins Medical School, and Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University. During his lifetime, Osler was a remarkable pollinator of ideas. He often returned to Montreal from travels in Europe and the US with important new ideas and methods, cementing McGill and the MGH’s reputations as major innovators in Canadian medicine.

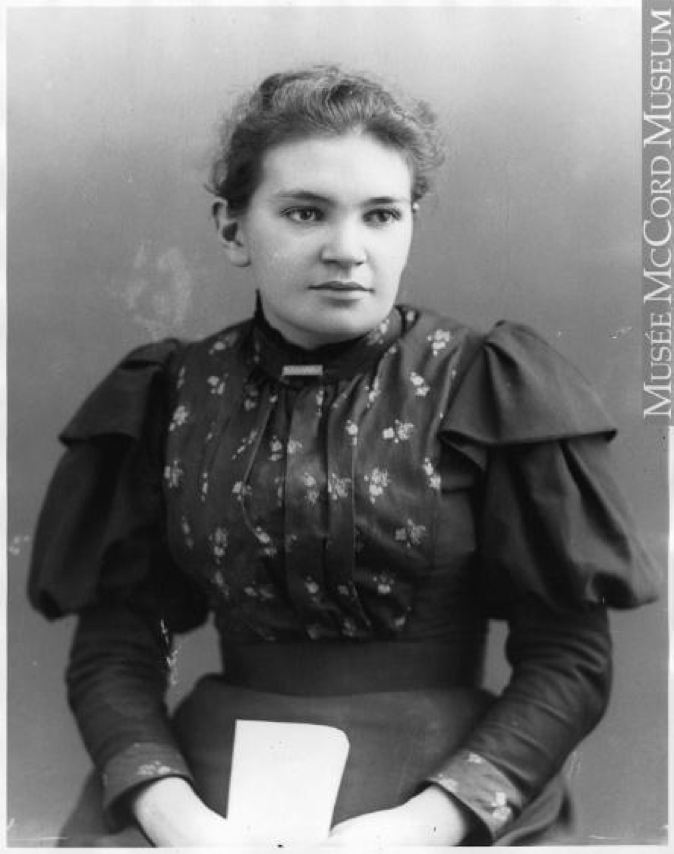

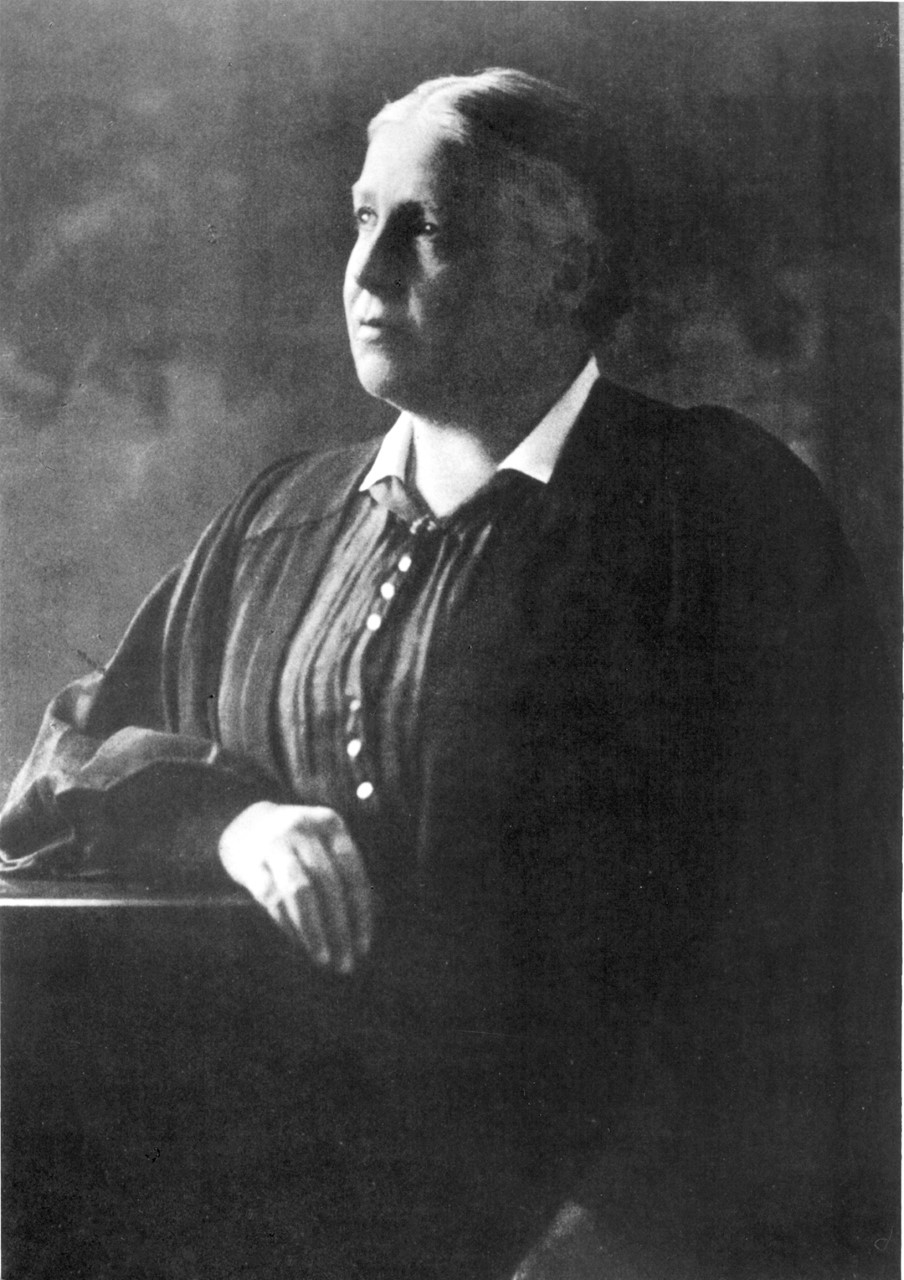

Osler corresponded with Dr. Maude Abbott for a number of years, mainly regarding her work cataloguing his MGH specimens as curator of the McGill Medical Museum (later renamed the Maude Abbott Medical Museum) and her contribution to Systems of Medicine. Although Osler was supportive of Abbott, his views that women weren’t suited to clinical practice reflected the general attitude in the McGill Faculty of Medicine at the time, which had denied Abbott entry into the medical program. She earned an MD from Bishops University in 1894, established a reputation as a foremost expert on congenital cardiac disease, and was granted an honorary MDCM from McGill in 1910.

Miss Maude E. Abbott, Montreal, QC, 1893. Wm. Notman & Son. McCord Museum, II-103172

This specimen was one of approximately eight hundred specimens Osler collected in the MGH morgue as pathologist to the hospital. His pathological studies formed the hospital’s first published medical report, and the first clinical report by a hospital in Canadian history.

Specimen 36: Heart and Aorta, Saccular Aneurysm. Maude Abbott Medical Museum

A Revolution in Surgical Practice: Sir Thomas George Roddick

Dr. Roddick, Montreal, QC, 1882. Notman & Sandham. McCord Museum, II-63859.1

Sir Thomas George Roddick was a McGill-trained physician and surgeon whose career began at the Montreal General Hospital. As an early adopter of germ theory, Roddick learned of a new surgical antiseptic technique developed by Joseph Lister. He visited the doctor in Edinburgh (1872) and again in London (1877) where he was able to secure one of Lister’s carbolic acid diffusers and bring it back to Montreal. The first of its kind in North America, Roddick consistently used the diffuser in the operating room and published his findings supporting its use. With the introduction of antisepsis, surgical mortality rates at the hospital dropped from 80% to less than 4%, forever changing the practice of surgery.

The introduction of antisepsis was so successful in lowering the mortality rate of surgeries that for the first time in history surgery began to branch out as a category separate from medicine. Renowned MGH surgeon Francis Shepherd recalls that after 1877 “no region was sacred to the surgeon’s knife,” since with lower risks came the viability of accessing the brain, spinal cord, abdominal cavity, and vital organs. In 1882 Roddick declared he would only practice surgery, effectively separating medical and surgical disciplines at the hospital for the first time. This decision would anticipate the flourishing of medical specialties to come. By the eve of the First World War, the hospital had transitioned away from a service that was mainly custodial to a place of healing.

While at the MGH, Roddick served as the chief surgeon of the Canadian Forces for the North West Rebellion. After he left the MGH, he continued to distinguish himself by playing an instrumental role in the creation of the Medical Council of Canada, championing public health issues, especially tuberculosis prevention, and founding the Alexandra Hospital for Infectious Diseases. He also served as the Dean of Medicine at McGill from 1901 to 1907.

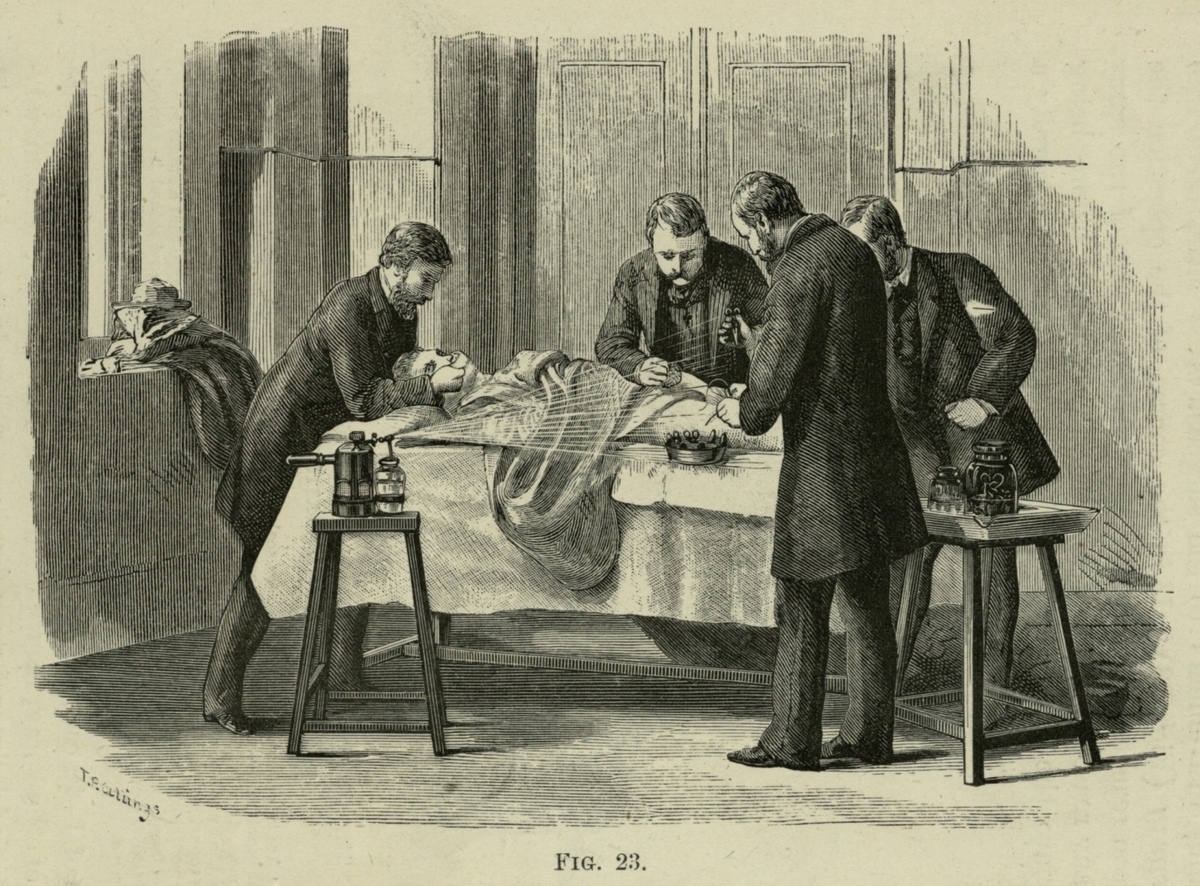

The early method involved spraying down the whole room in carbolic acid carried in a thick haze of steam. Over time, Roddick observed that the carbolic acid could be more centralized to the surgical area rather than spraying the whole room, but this still came at a cost. Staff had begun to suffer from burns and Roddick himself developed asthma. This led to the first use of gloves and consequently the much more efficient aseptic procedures now used in hospitals.

Use of the Lister carbolic spray, Antiseptic surgery, 1882. Wellcome Collection

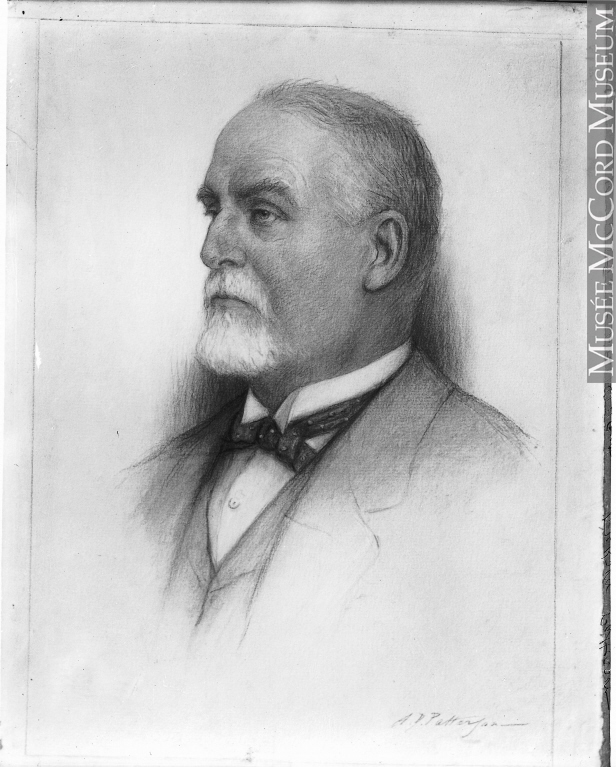

Dr. Francis J. Shepherd (1851-1929) was a notorious MGH surgeon and dermatologist who worked at the hospital for over forty years. Witnessing the antiseptic revolution, he wrote in his history of the MGH that “the operating room, instead of being a shambles and the tables and floor covered with the dried blood of many victims, now became excessively clean. New antiseptic operating tables with glass tops were bought, tiled floors were laid, and the seats scrubbed and scoured. Instruments were sterilized before operation, and the surgeon paid great attention to his hands and wore a snow-white gown. The field of operation also was sterilized and rendered antiseptic and the greatest care was taken to exclude germs, which then were quite new discoveries…” Origin and History of the Montreal General Hospital, 1925.

Dr. Shepherd, drawing by and copied for Andrew Dickson Patterson, 1929. Wm. Notman and Son. McCord Museum, VIEW-24585

Nora Livingston

and the beginning of the

MGH School of Nursing

General Hospital Nurses, Montreal, QC, 1895. Wm. Notman & Son. McCord Museum, II-113321

In the late 1800s, English nursing reformer Florence Nightingale laid the groundwork for the profession of nursing worldwide. Based on science and rigorous training, her reforms provided a model system for training nurses that was adopted by the first Canadian nursing schools soon after.

“I use the word nursing for want of a better. It has been limited to signify little more than the administration of medicine and the application of poultices. It ought to signify the proper use of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet and the proper selection and administration of diet – all at the least expense of vital power to the patient.” –Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing

Cover of Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing (first published 1859), courtesy of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

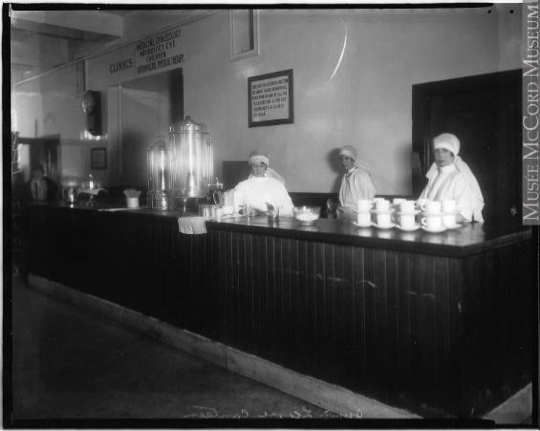

At the MGH, early nurses lacked formal training and were little more than glorified housekeepers, despite several attempts to improve the situation. In 1890, the board of management hired Gertrude Elizabeth (Nora) Livingston, a New York-trained nurse. She immediately instituted crucial changes: charting, fire prevention measures and an improved diet kitchen. She also negotiated better working and living conditions for nurses.

Inspired by Nightingale, Livingston established what would become a renowned training school whose curriculum was composed of scientific and practical courses. In 1906, the hospital hired Flora Madeline Shaw (Class of 1896), who became the first nursing instructor in Canada. Shaw was recognized internationally for her leadership and later became the founding director of the McGill School of Graduate Nurses.

L-R: Julia English, Christina Mackay, Nora Livingston, Jessie Preston, Dr. R.C. Kirkpatrick, Fanny Quaife, Georgina Carroll. Not pictured: Alicia Dunne, Ellen Chapman

School of Nursing Class of 1891 (first graduating class), courtesy of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing.

Fabric swatches showing School of Nursing’s ‘MGH’ monogram print, with Margaret Suttie’s MGH School of Nursing graduate’s pin. Courtesy of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

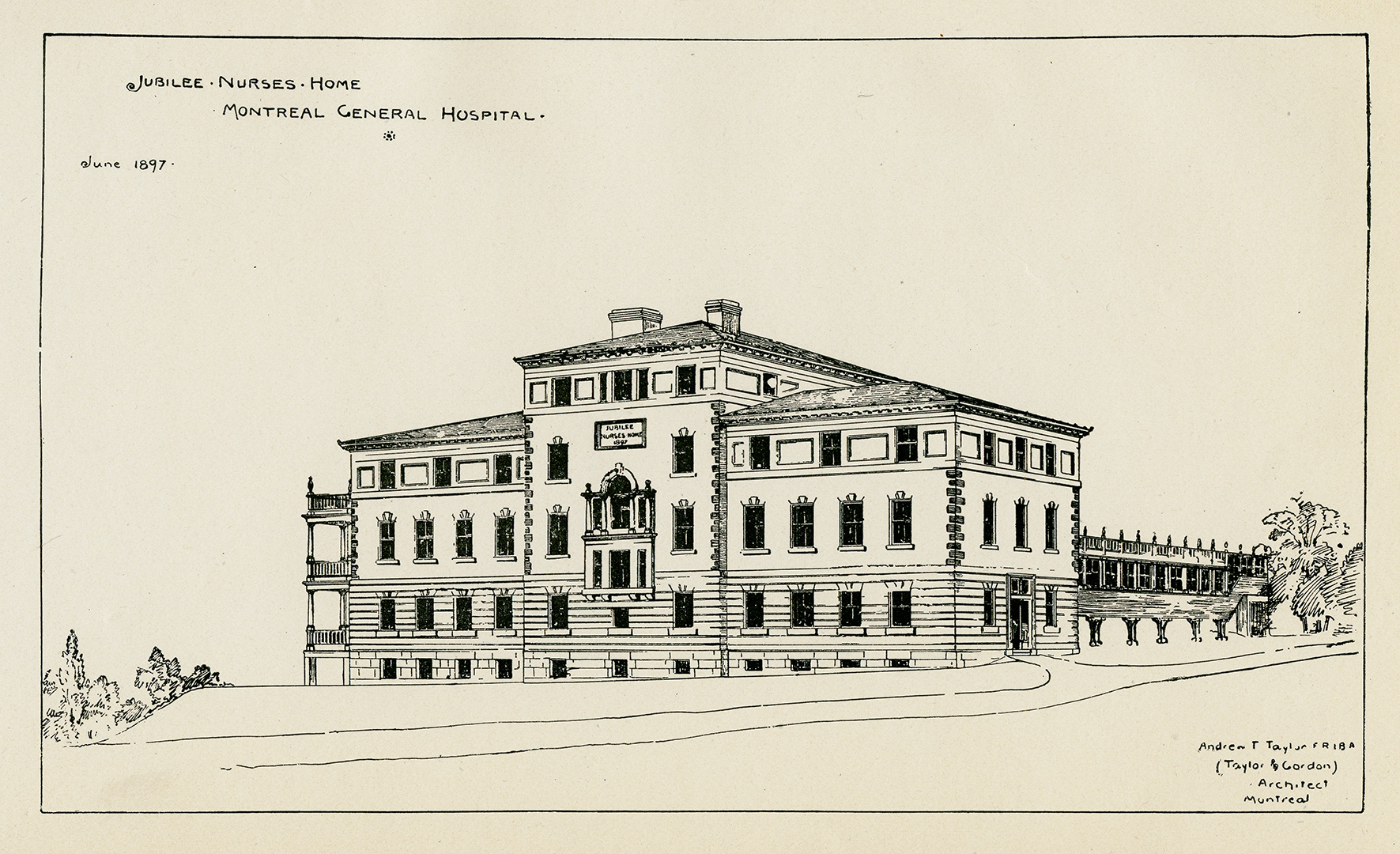

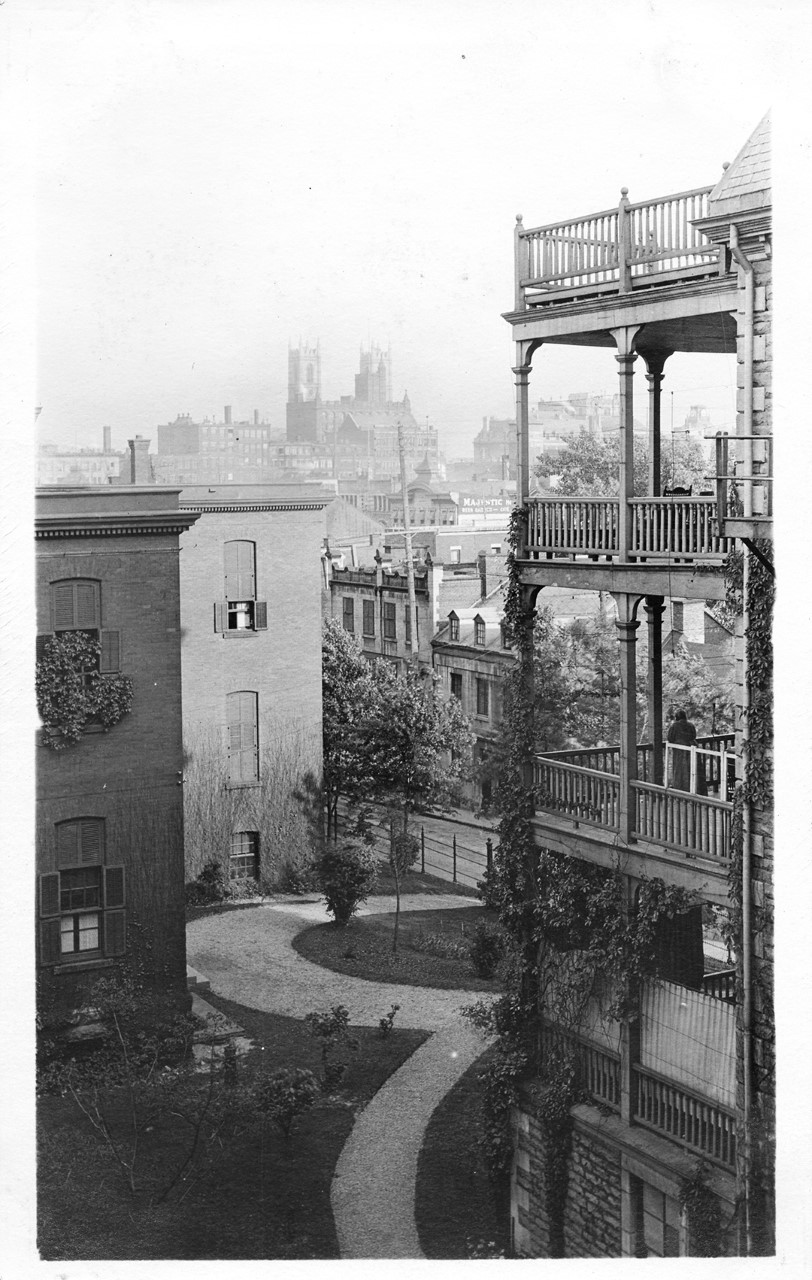

Livingston’s initiatives attracted so many women into nursing that she opened a new residence called the Jubilee Nurses Home in 1897, in honour of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The architecture’s stateliness reflected recognition of the increasing importance of the nursing profession.

Photo of engraving of exterior view of Jubilee Nurses’ Home, Montreal General Hospital, June 1897. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.01.11

In 1905, recognizing that uniting together could enhance and promote nursing as an honourable profession, graduates of the MGH School of Nursing formed the “Nurses Club” (later the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing). The group committed itself to education, nursing and social reform, and a sick benefit fund for its members.

The galleries served an important function in the healing process, as they provided fresh air and sunlight.

L-M Gallery, Montreal General Hospital, c. 1905. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Mann Fonds, 2017-0001.01.31

Montreal from Street Railway Power House chimney, QC, 1896. Wm. Notman & Son. McCord Museum, VIEW-2943.

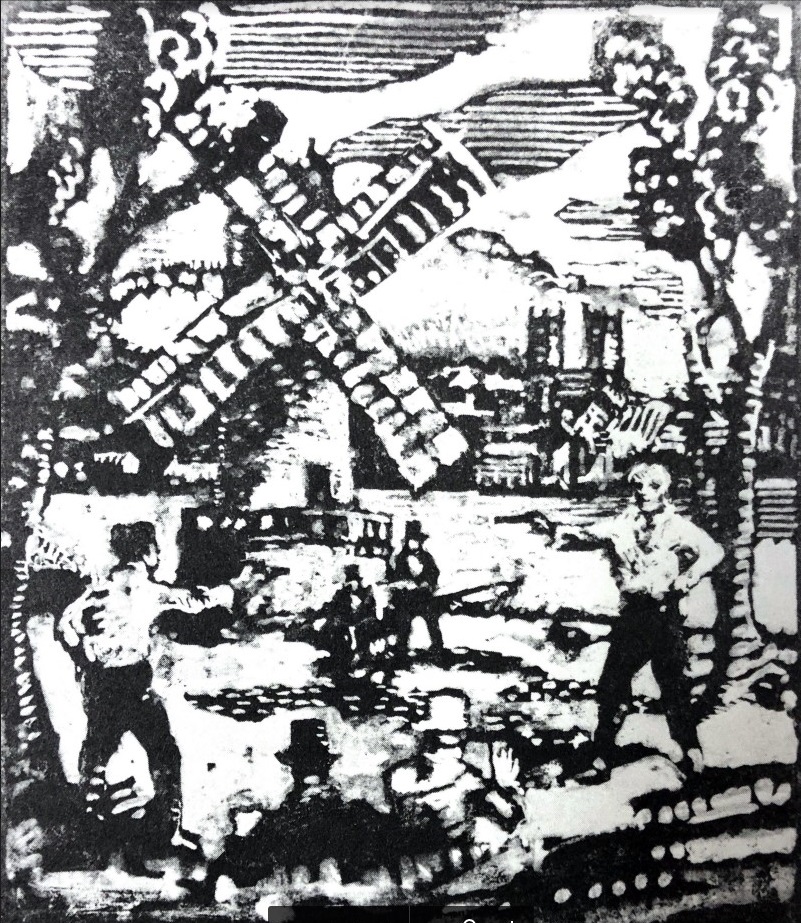

This moralizing engraving illustrates contrasting living situations of upper- and working-class households.

John Henry Walker, Family Life, 1850-1885. McCord Museum, Gift of David Ross McCord, M930.50.2.263

Social Work: A Visionary Philanthropic Commitment

In 1913, one quarter of the 769 patients served by MGH social workers were women and children who were transferred to the Protestant Orphan Asylum for ongoing care.

Ladies Benevolent Institution, Montreal, QC, 1909. Wm Notman & Son. McCord Museum, II-174417

Chart showing growth of population of the city, by Linda Jackson.

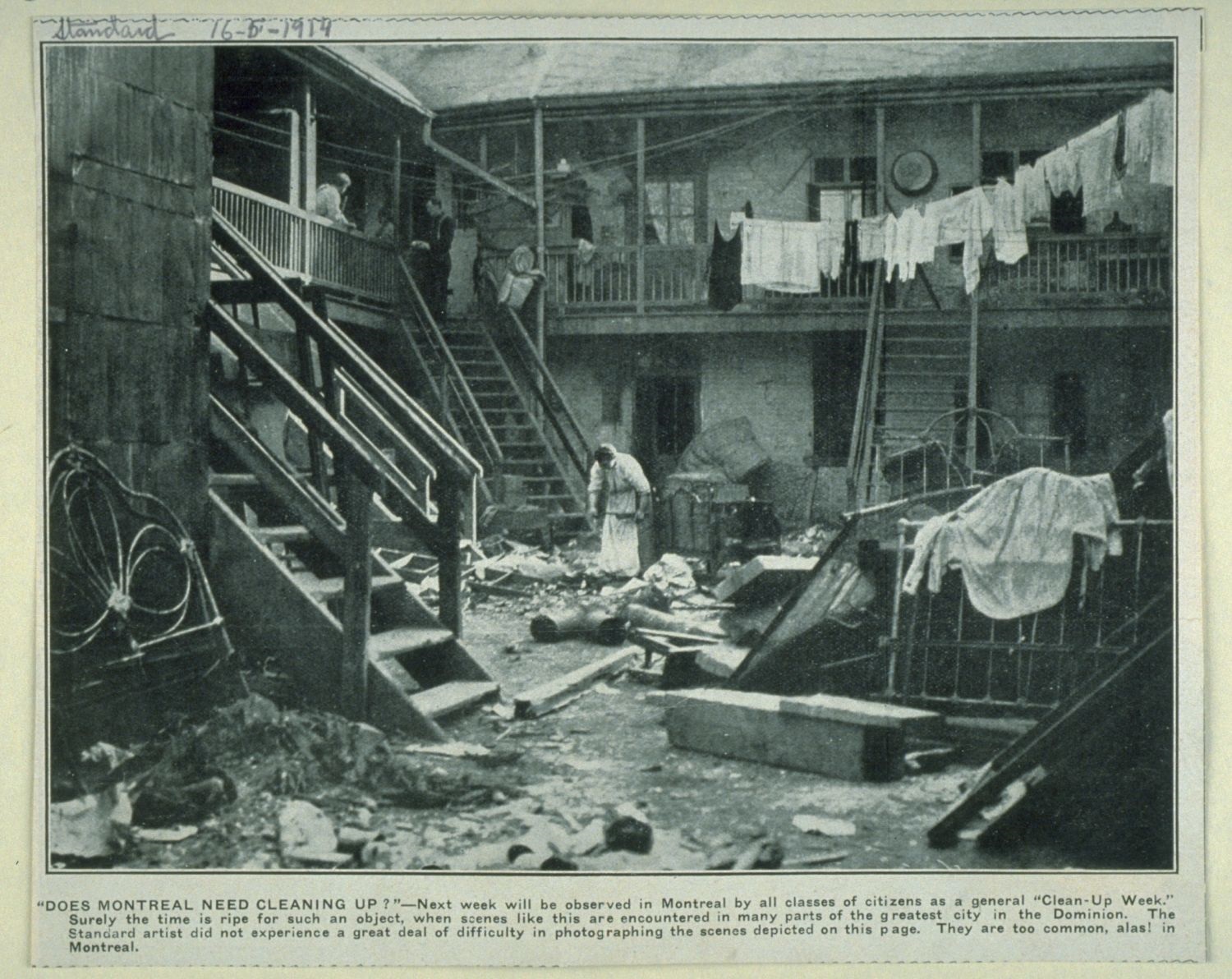

As Montreal rapidly industrialized, it grew into a city of over three hundred thousand inhabitants by the end of the nineteenth century. The MGH adapted to these changes with the expansion of its services as it endeavored to meet the demands of a newly urban population and its health problems. Infectious diseases and sanitary problems remained rampant, and the infant mortality rate was shockingly high – one in four children did not survive infancy – largely due to slum conditions in the city’s working class areas, alongside contaminated water and milk supplies.

The Social Service department was established at the MGH in 1911 through the efforts of Reverend John Lochhead of the Melville Presbyterian Church in Westmount. Inspired by Richard Cabot at the Massachusetts General Hospital, who pioneered hospital-based social service programs, Lochhead raised funds for the salary of a full time social worker, Emma J. Foulis, who was hired in 1912 and did a two-week apprenticeship at the Massachusetts General.

Though ignored at first by hospital staff, the department – with the help of twelve volunteers – identified charitable agencies that could provide services to the poor and homeless, and arranged for transfers of convalescing and chronically ill patients to other institutions at a time when the hospital’s shortage of chronic care beds desperately needed addressing. The Melville Church congregation also purchased a residence on the summit of Westmount Hill for the MGH to use as a convalescent home, a precursor to the Montreal Convalescent Hospital.

Ladies Benevolent Institution, Montreal, QC, 1909. Wm Notman & Son. McCord Museum, II-174417

SOCIAL WORK: A VISIONARY PHILANTHROPIC COMMITMENT

Early Years - 1818-1914Chart showing growth of population of the city, by Linda Jackson.

SOCIAL WORK: A VISIONARY PHILANTHROPIC COMMITMENT

Early Years - 1818-1914