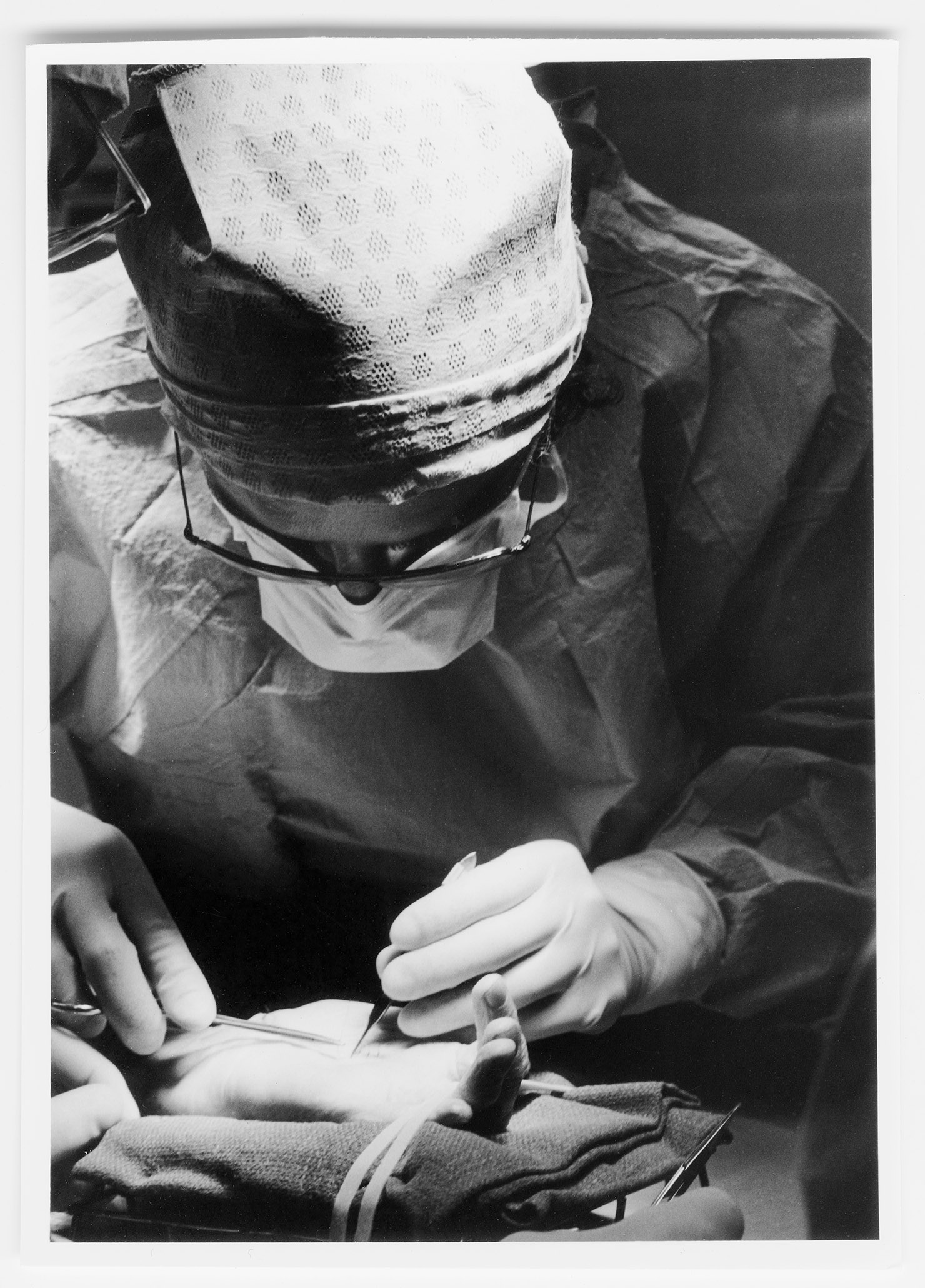

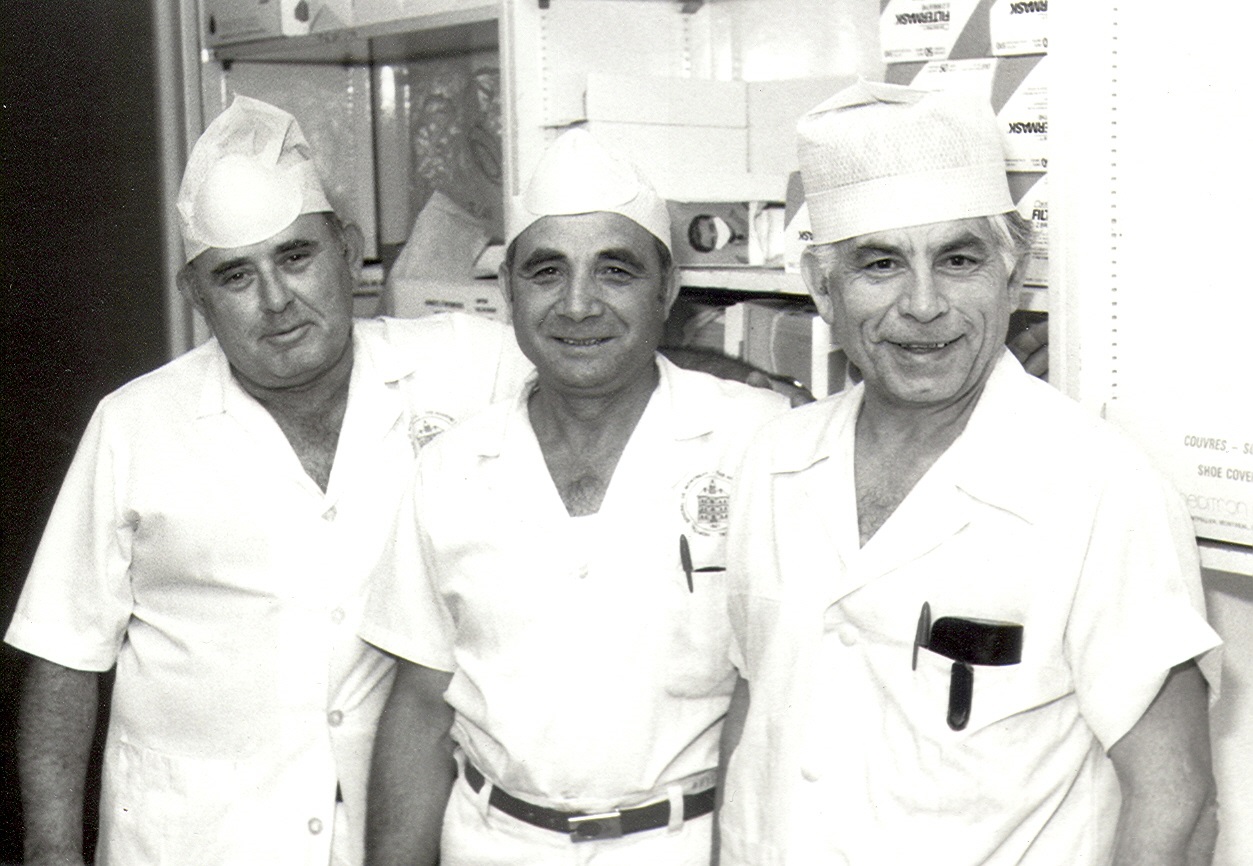

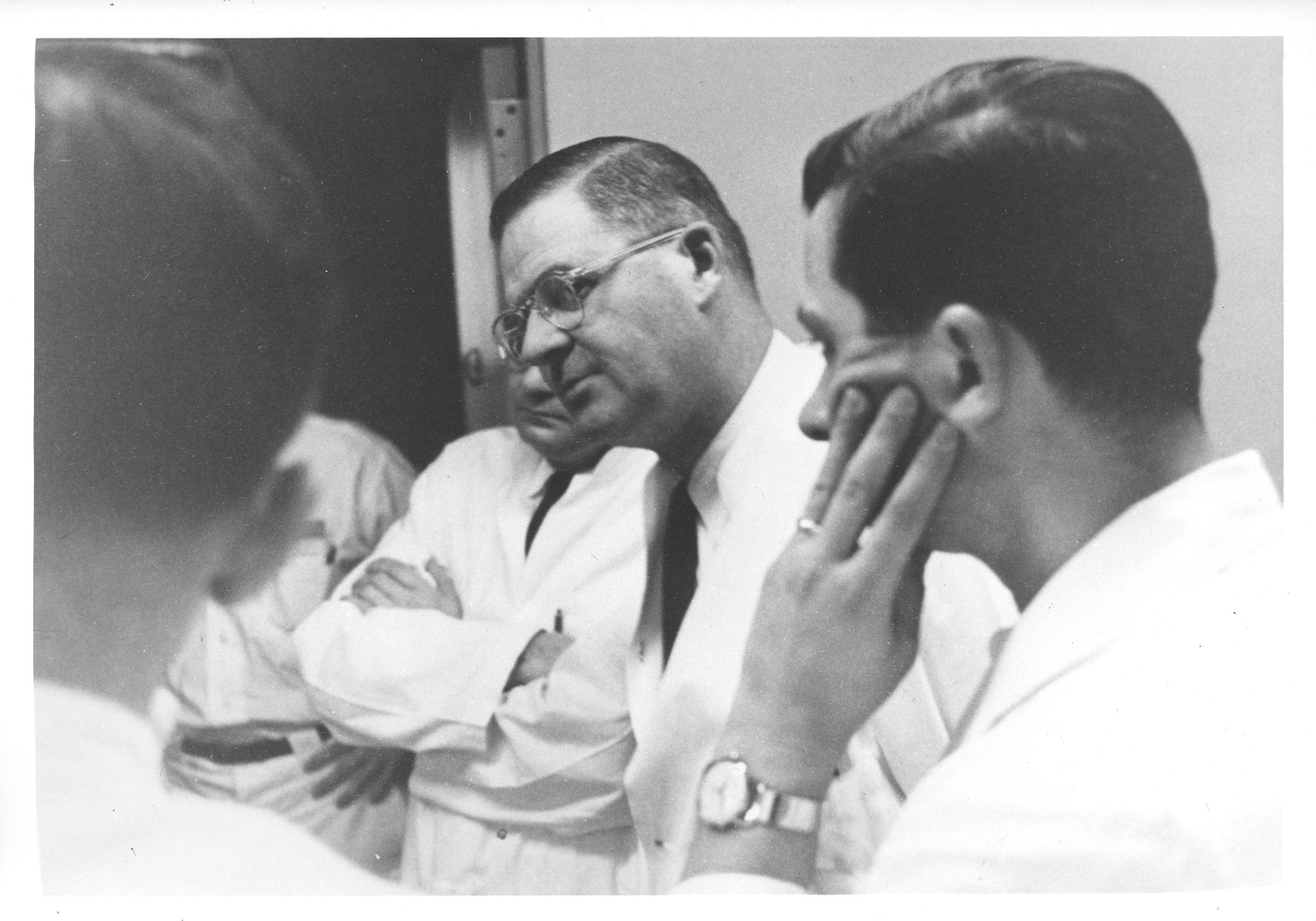

Albert Cloutier, OR no. 10 – The Montreal General Hospital, featuring Drs. S.A. MacDonald, H. Rocke Robertson, and H.J. Scott, 1961. Collection of Dr. David Mulder, courtesy of Medical Multimedia Department of the MUHC, photographed by Michael Cichon

Introduction

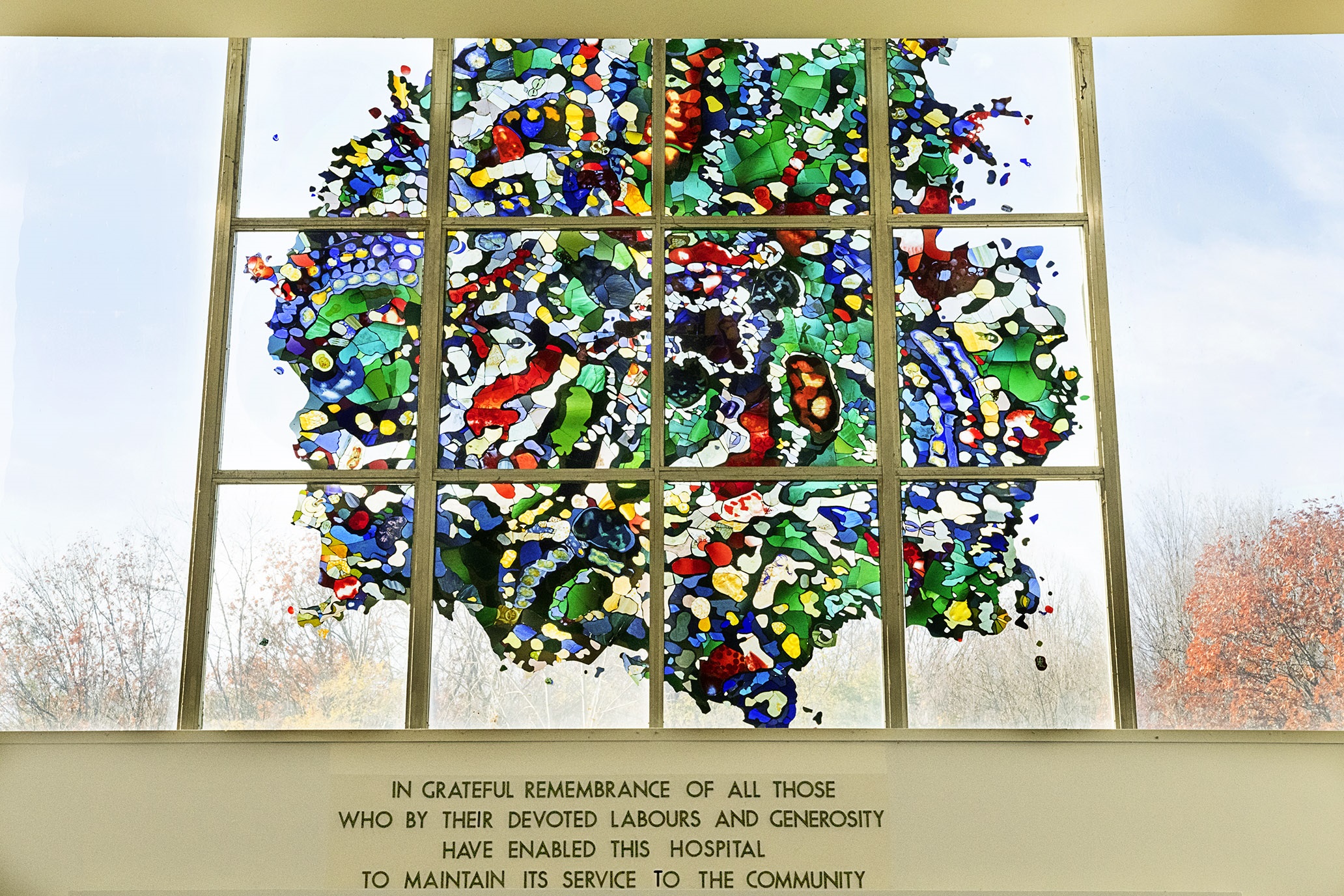

This stained glass window was donated by Melvyn Angus, one of the hospital’s most dedicated supporters. For the design, British stained glass artist Lawrence Lee took inspiration from the structure of cells when viewed under an electron microscope. The window symbolizes a new period in the history of the hospital, as technological innovations and the expansion of clinical research greatly expanded the horizon of medical and surgical knowledge. During this time, the MGH made a number of internationally recognized contributions.

Stained glass window by artist Lawrence Lee. Courtesy of the Medical Multimedia Department of the MUHC. Photographed by Michael Cichon.

The postwar years at the MGH were a microcosm of the massive changes occurring in Quebec and across the country. Social reforms of the 1960s and ’70s, like the rapid advancements affecting medical care, brought major change to the hospital.

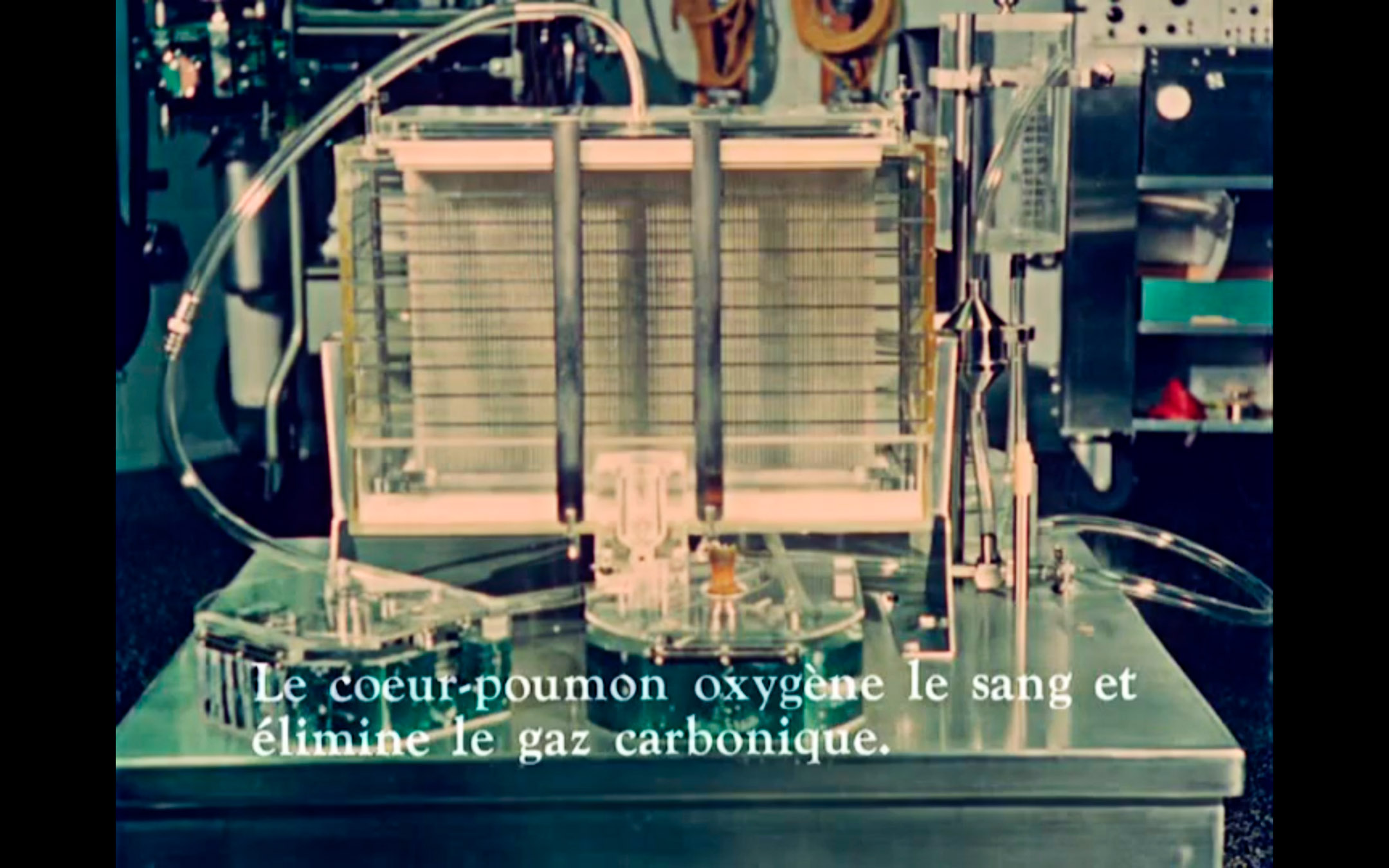

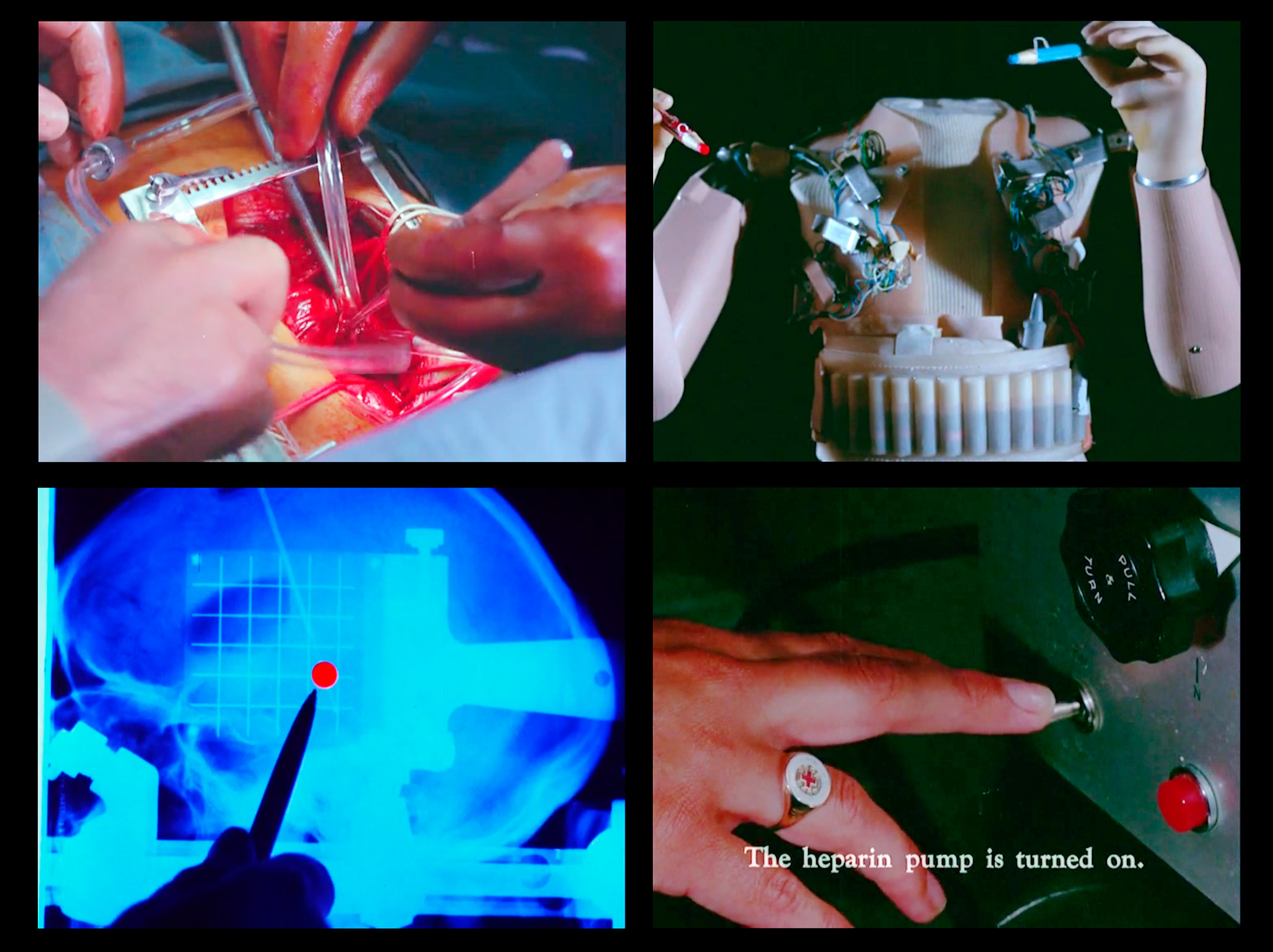

In 1967, Montreal hosted one of the most successful world fairs of the 20th century. Expo 67 had a pavilion dedicated entirely to recent medical advances. As part of this pavilion’s multimedia spectacle, Robert Cordier’s experimental film Miracles in Modern Medicine made headlines for shocking viewers with its graphic depictions of live births and surgical interventions. The pavilion was developed in consultation with local doctors, including the MGH’s Phil Gold, and was designed to enlighten a general audience on aspects of medical and surgical care that had previously been obscured from view. The pavilion design emphasized the futuristic, technology-driven aspects of medical care that had been in development since the war. Cordier’s film was partially shot in the MGH’s renal dialysis unit (as well as the Royal Victoria Hospital’s Women’s Pavilion, McGill’s nuclear medicine facility, Hotel Dieu, and the Rehabilitation Institute of Montreal).

Stills from Robert Cordier’s Miracles in Modern Medicine, 1967. Library and Archives Canada, 1973-0265, copyright Robert Cordier. Curatorial consultant: Steven Palmer

As World War II came to an end, war-related scientific and technological breakthroughs were repurposed for medical research and treatment, leading to rapid progress in those areas. At the same time, MGH management formally recognized the importance of research in securing the hospital’s ongoing reputation as a leading academic medical centre. The decades that followed saw increasing emphasis on (and support for) clinical investigation. Medicine and surgery became more specialized as the complexity of medical care increased. To support these advances, the educational requirements for health professionals increased, as did the need for those working in allied health disciplines.

Through these changes, philanthropic and volunteer efforts continued to evolve within the institution, playing an invaluable role supporting research, planning, and patient programs.

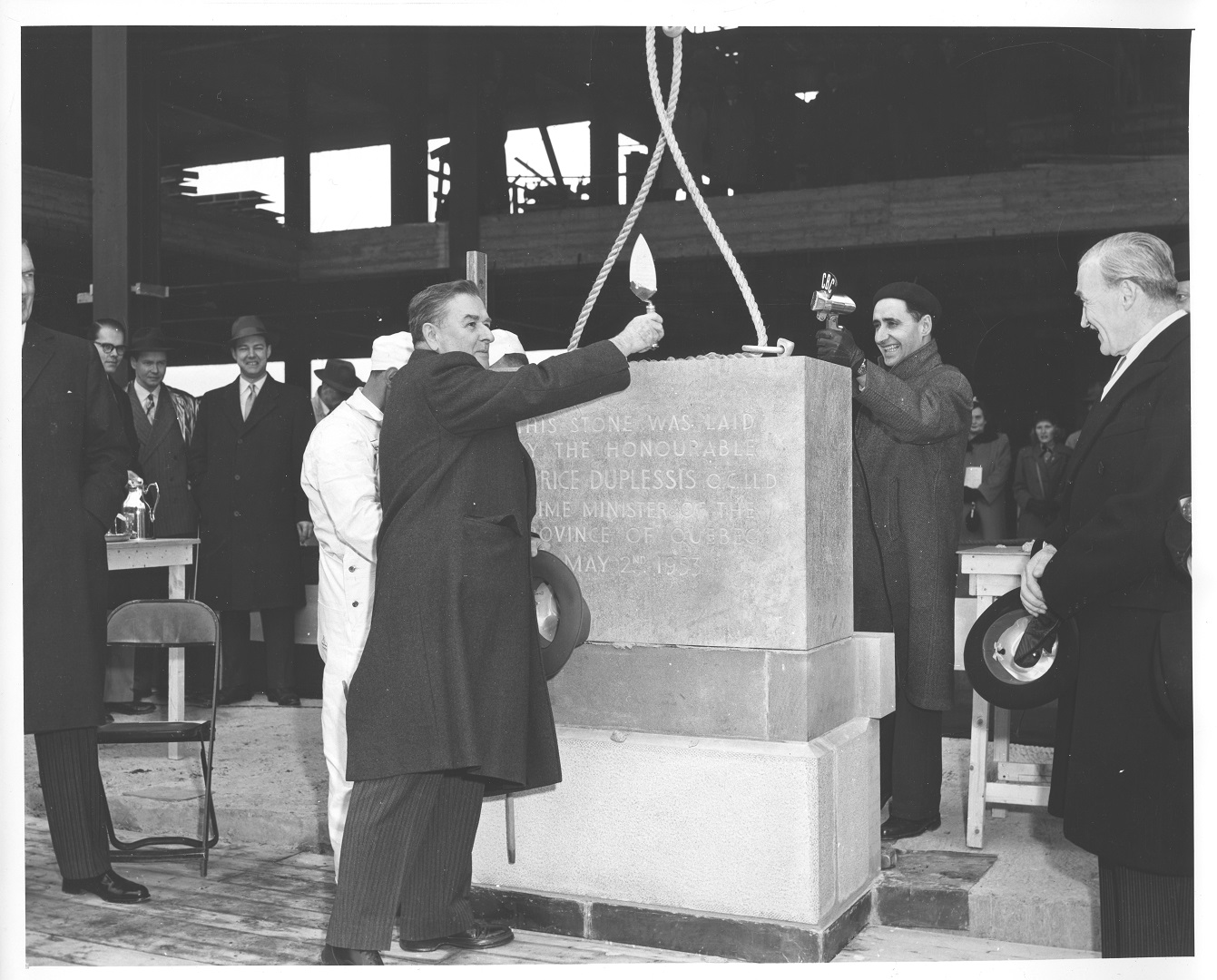

Rebirth of the MGH

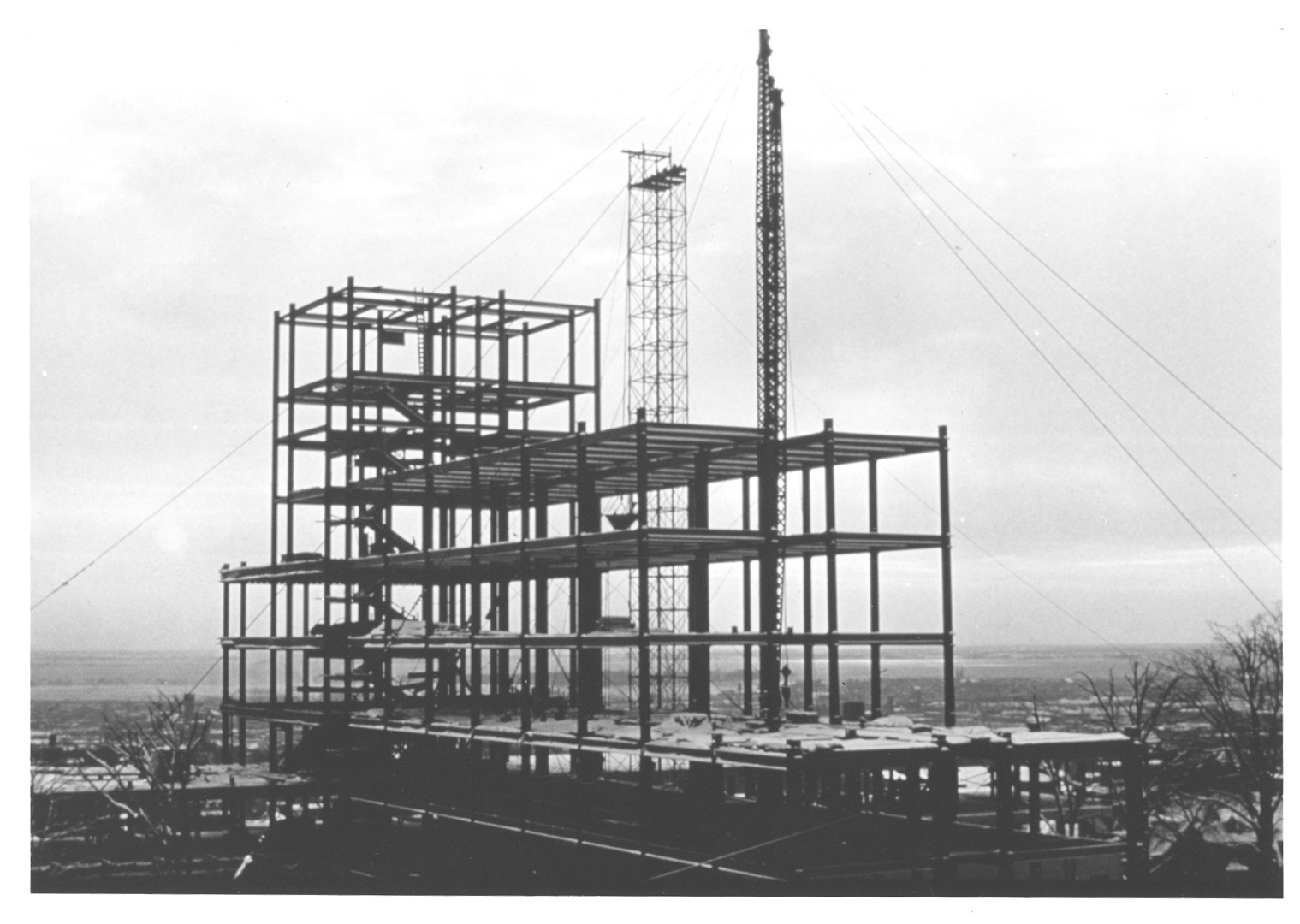

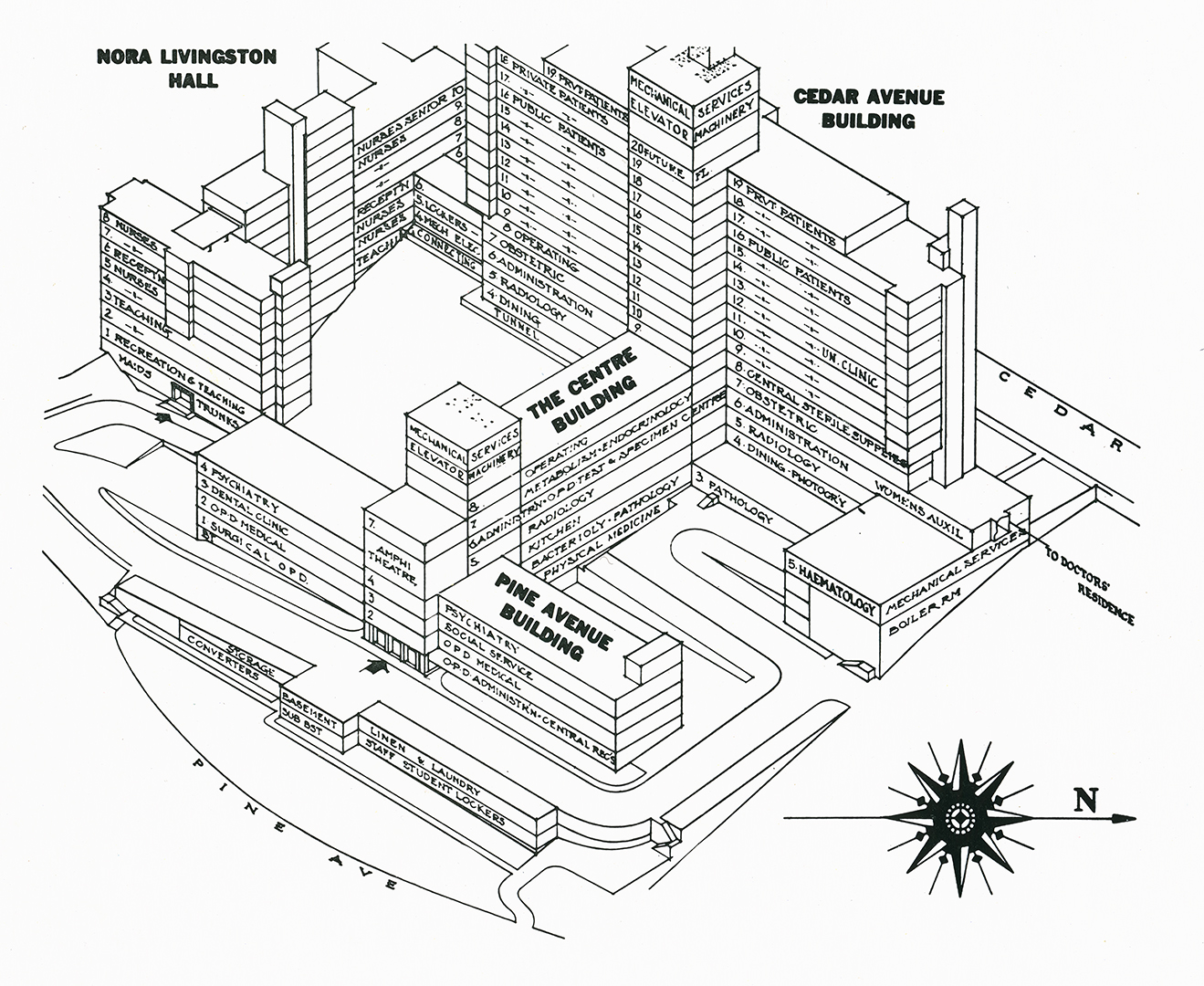

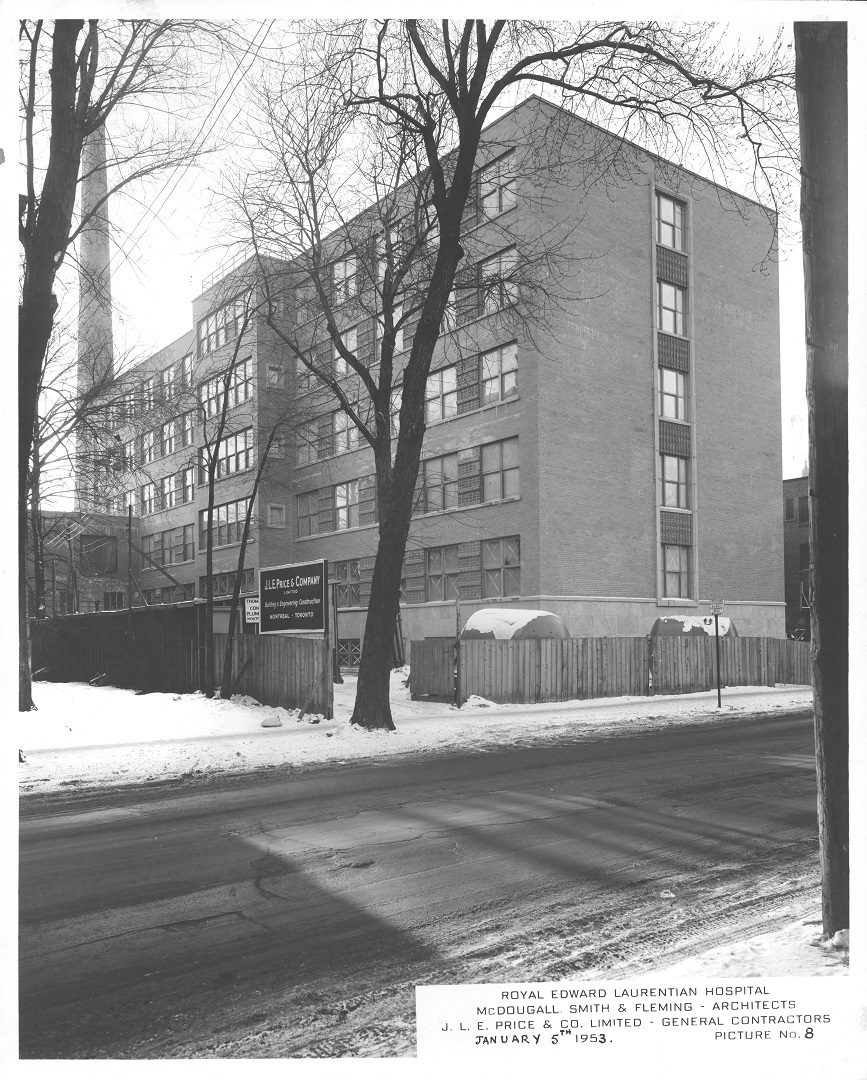

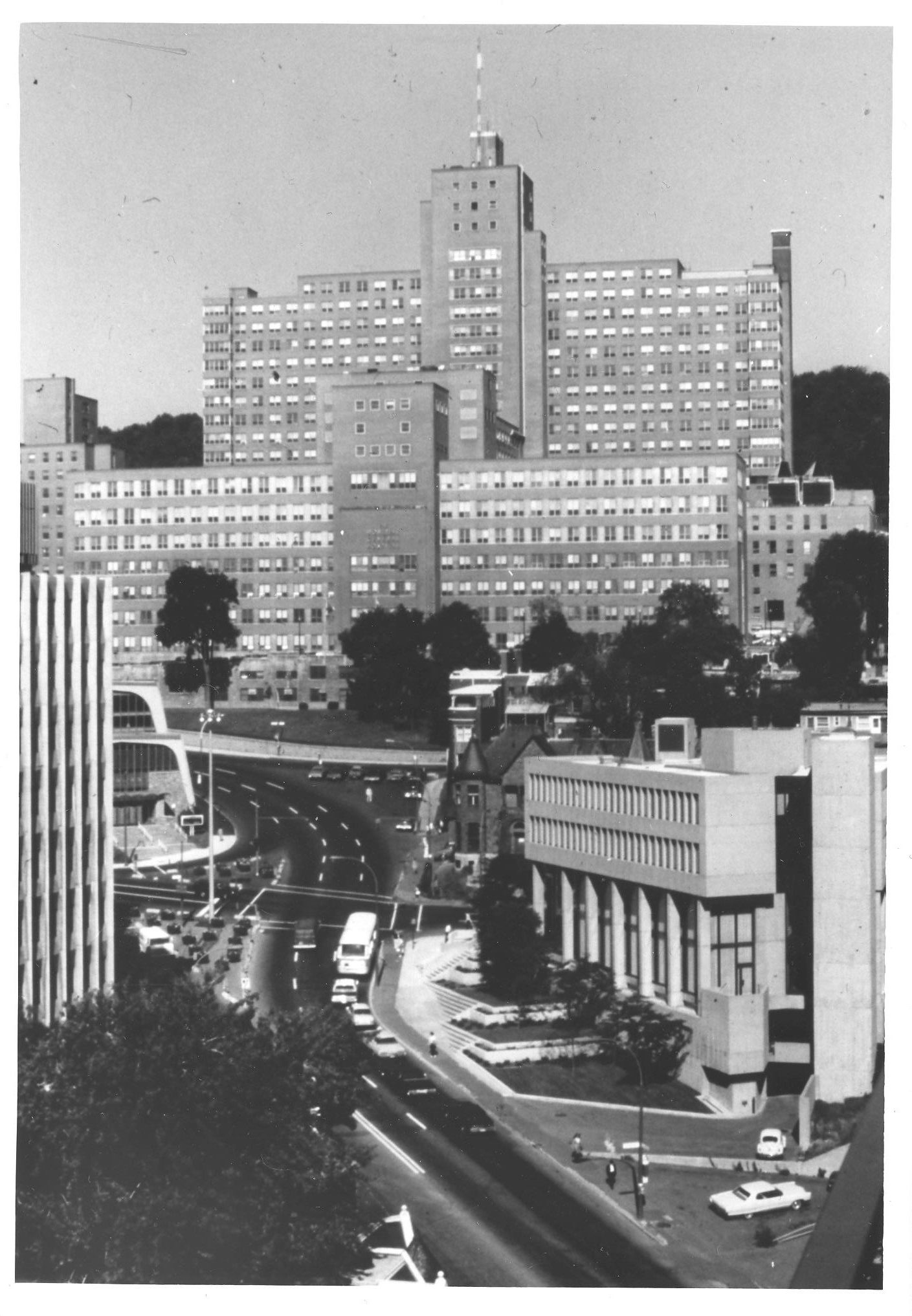

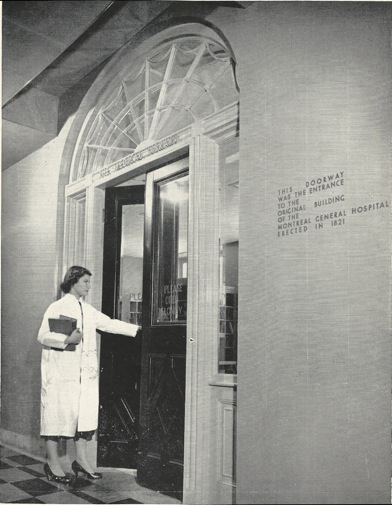

In the late 1940s, medical personnel realized that if the MGH was to remain a leading academic medical institution, they would need to convince the board of management to relocate. It had become clear that they had outgrown their present facilities: the buildings at both Central and Western divisions had become obsolete, and the cost of operating two sites prohibitive. Coupled with the desire to be closer to McGill and its sister institutions, the committee was tasked with finding a solution resolved to relocate to the southwestern slope of Mount Royal, on a strip of land between Cedar and Pine avenues.

Montreal Children’s Hospital, photographed by Robert Derval, 2000. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Montreal Children’s Hospital Audio-Visual Department Fonds, 2014-0015.04.748

The hospital was designed by the local architectural firm McDougall, Smith and Fleming, and reflected the massive complexity of a large-scale, urban teaching hospital of its day. The finished building shared architectural components with the Montreal Children’s Hospital (which purchased and expanded the Western Division upon its relocation) and the Montreal Chest Institute.

Technology and the Changing Face of Bedside Care

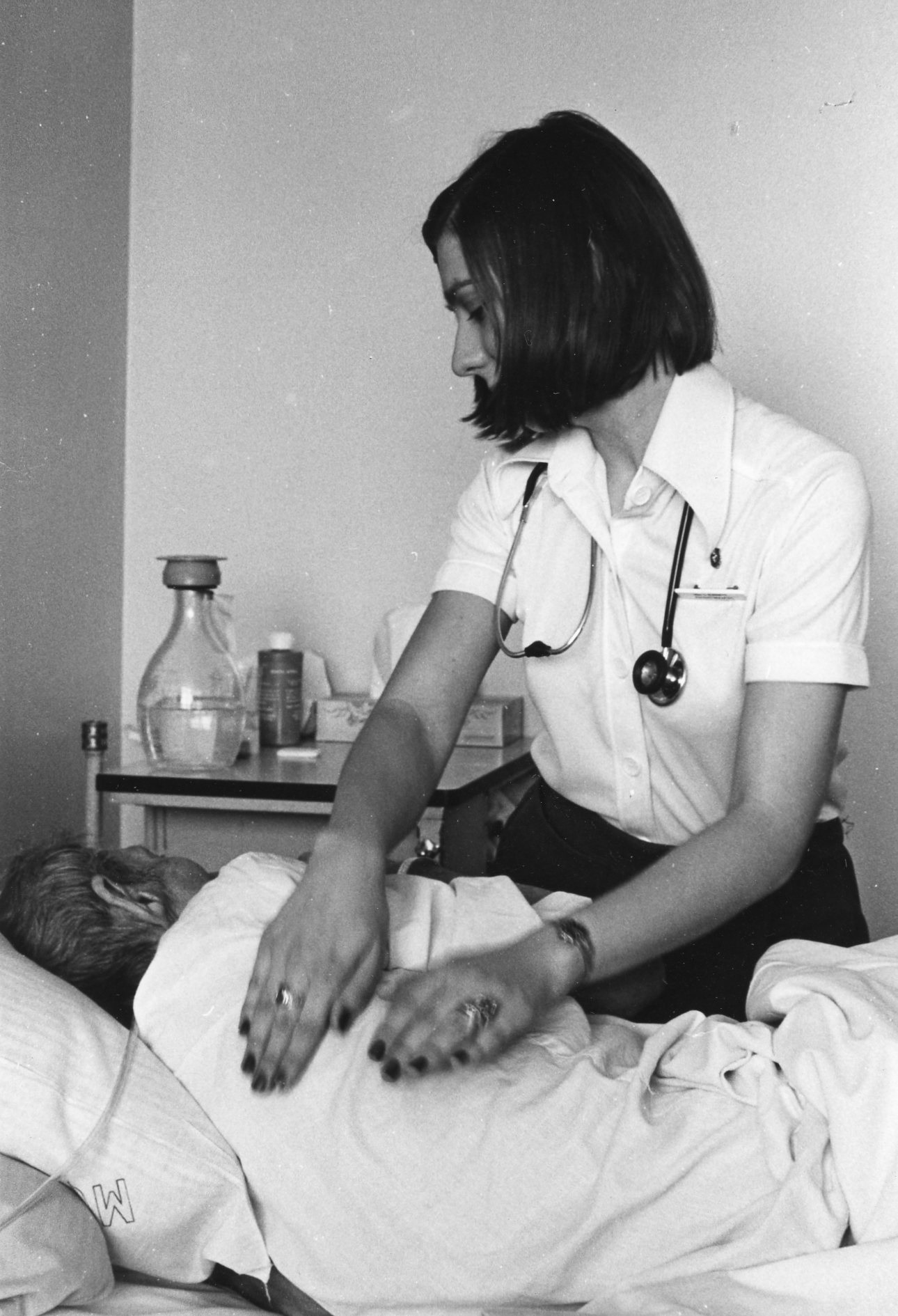

The new hospital posed a different set of challenges for nurses due to the design of the units. Whereas the old hospital had large wards that allowed nurses to supervise dozens of patients at a time, the new nursing units consisted of single, two- and four-bed rooms. While this reflected a shift towards more patient privacy and the need for infection control, it also required more nursing staff.

As medical and surgical treatment options expanded, the new hospital needed to find a way to integrate intensive monitoring and care beyond what was available in the recovery room. These rooms used monitoring technologies that allowed constant surveillance of patients, and were staffed with nurses who had specialized knowledge and skills. The first intensive care units were carved out of existing clinical space and staffed with much higher nurse-to-patient ratios.

The hospital installed its first Intensive Care Unit in 1960: a surgical ICU for patients recovering from complex cardiac procedures. The first Coronary Care Unit opened in 1966.

Surgical Intensive Care Unit, c. 1981. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.1013

Nurses working in the CCUs were trained to interpret ECGs, which were transmitted from patient beds to a central monitoring station, and were authorized to resuscitate patients in the event of a cardiac arrest.

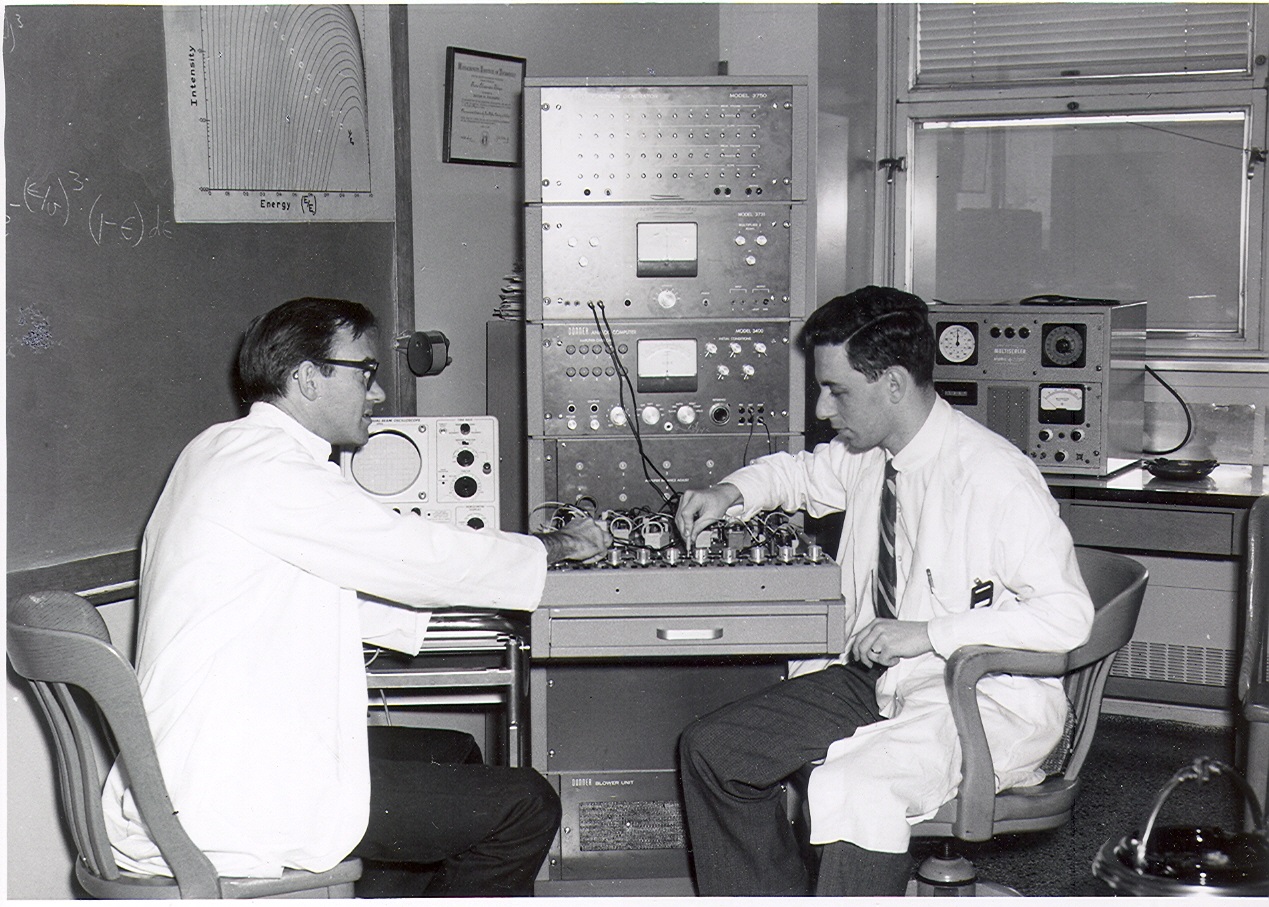

Cardiac Monitoring Unit, c. 1970. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2104-0014.04.669.2

Using funds raised by the hospital’s new research committee, Physician-in-Chief E.S. Mills opened the University Medical Clinic (UMC) in 1952. The UMC was to have an enormous impact on the hospital’s reputation for research and on the coordination of its activities. Following pressure from McGill to apply the same academic principles of advancement through research as in the Department of Medicine, the MGH recruited H. Rocke Robertson to be Surgeon-in-Chief in 1958. He established the University Surgical Clinic (USC) the following year.

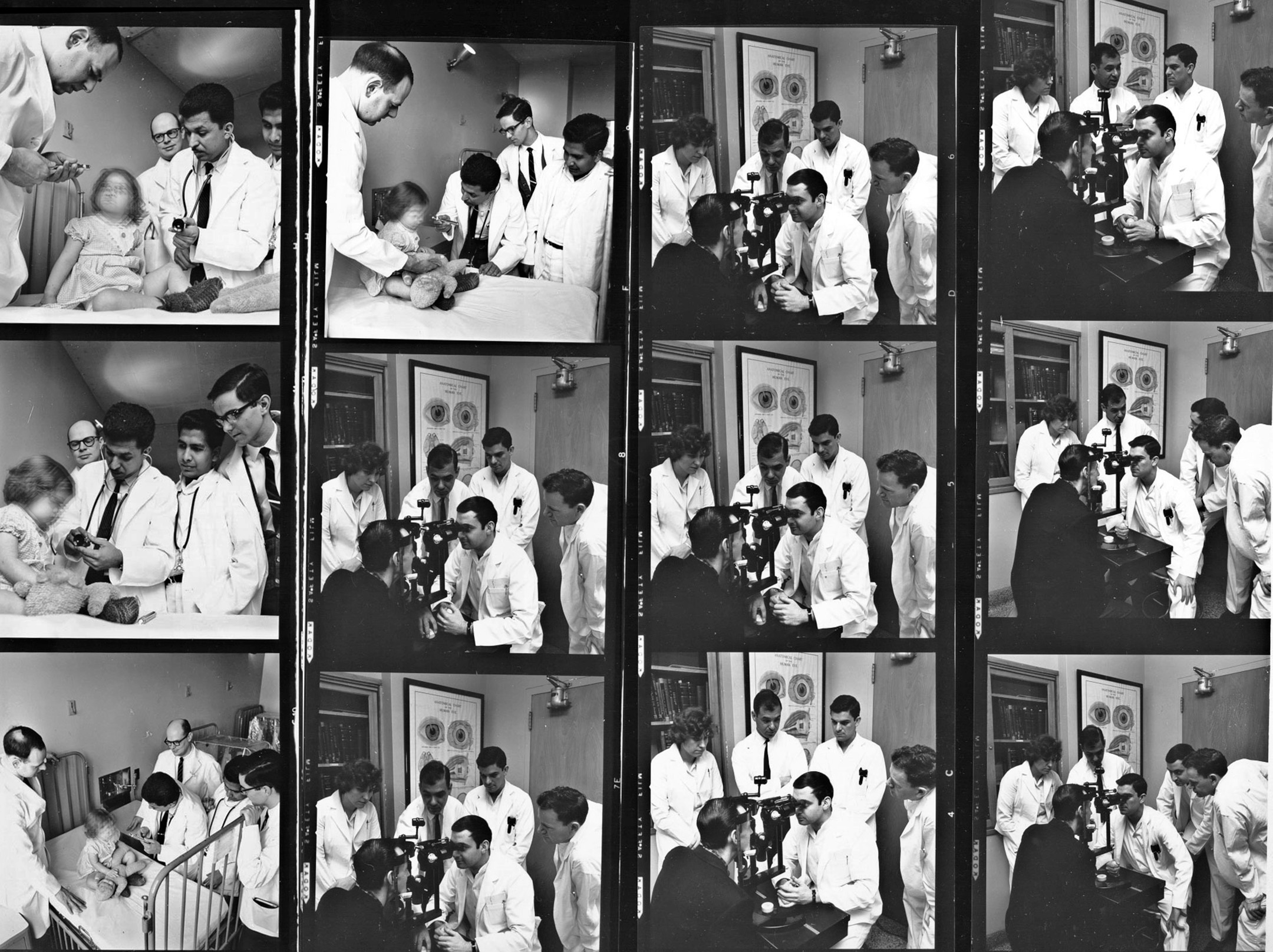

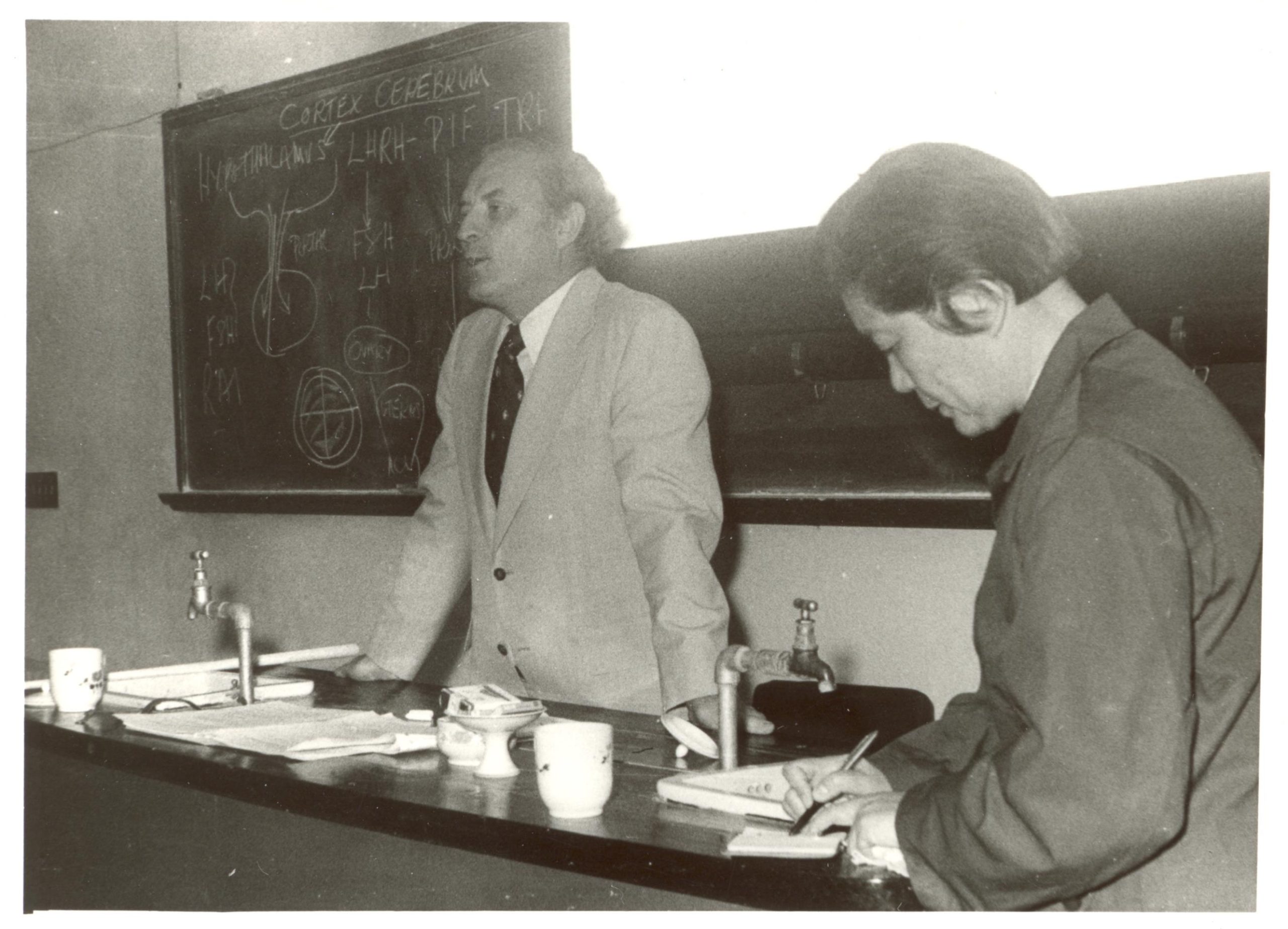

Clinical Research and Teaching

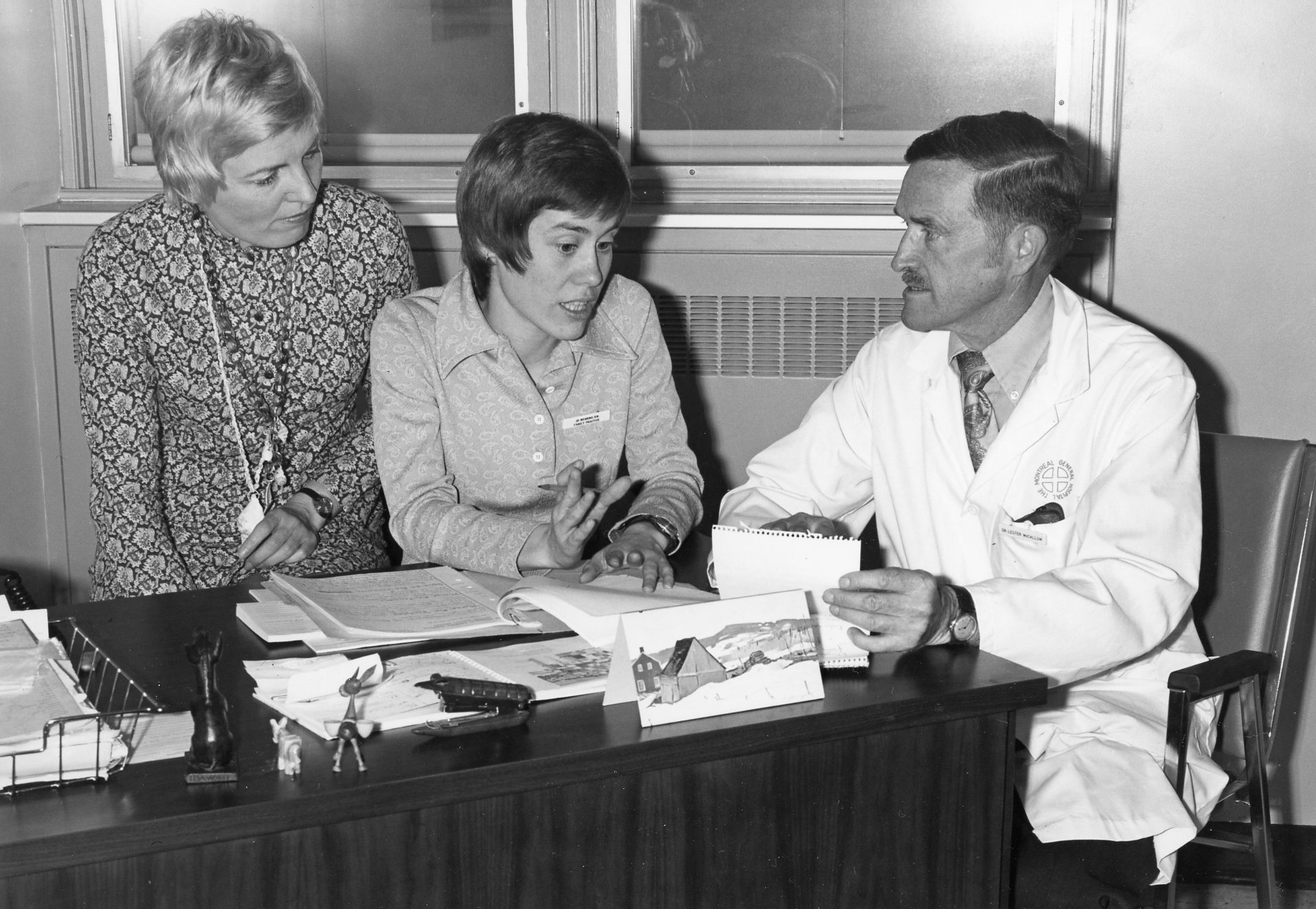

These new research initiatives in the hospital marked the beginning of postgraduate training for a growing population of clinicians. When Mills resigned in 1957, Douglas Cameron became Physician-in-Chief, and set about restructuring the clinical units within the hospital so that they could be close to the hub of research activity at the UMC. Realizing that research and teaching could be more effectively concentrated on a specialty-by-specialty basis, he created Divisions under the Department of Medicine, with geographic-full-time chiefs who acted as McGill professors and directors of research in their various specialties. Subsequently, each Division developed its own lines of investigation, and advanced according to its own trajectory – these are the specializations in medicine and surgery that we recognize today.

The activity generated in the medical clinics boosted the academic reputation of the hospital: between 1955 and 1960, the postgraduate training population of the hospital went from fifteen to 250. The hospital continued to attract increasing numbers of researchers from all over the world.

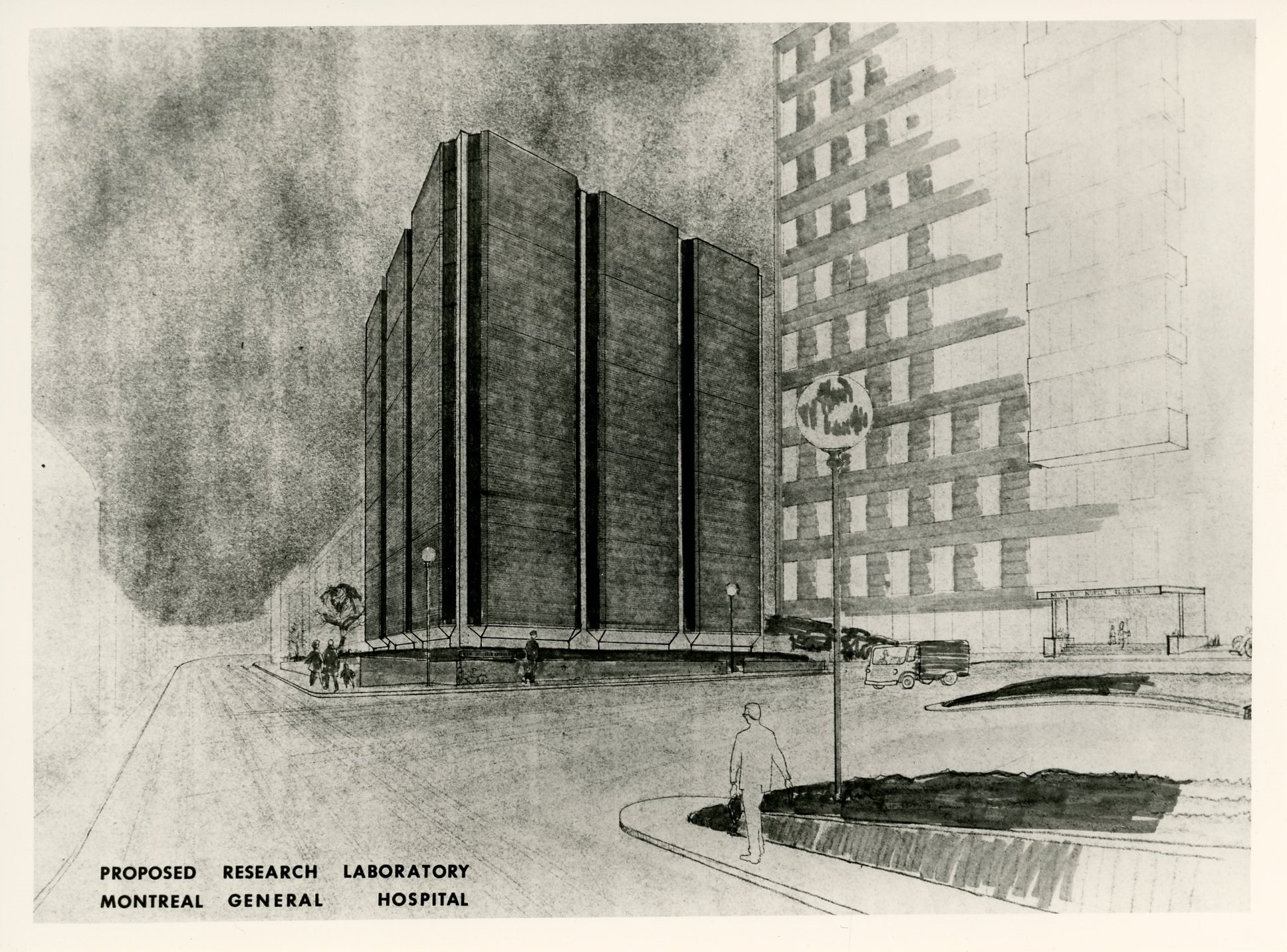

As research activity at the hospital picked up – requiring more staff, space and equipment – the hospital raised funds to build an adjacent five-story research centre that remains active today. Over the years, the Research Institute of the MGH has hosted a wide range of distinguished researchers, who have made international headlines with their contributions to the fields of cancer research, immunogenetics, neural regeneration, cardiac surgery, pain, genomics, and more.

Significant Achievements in Medicine and Surgery

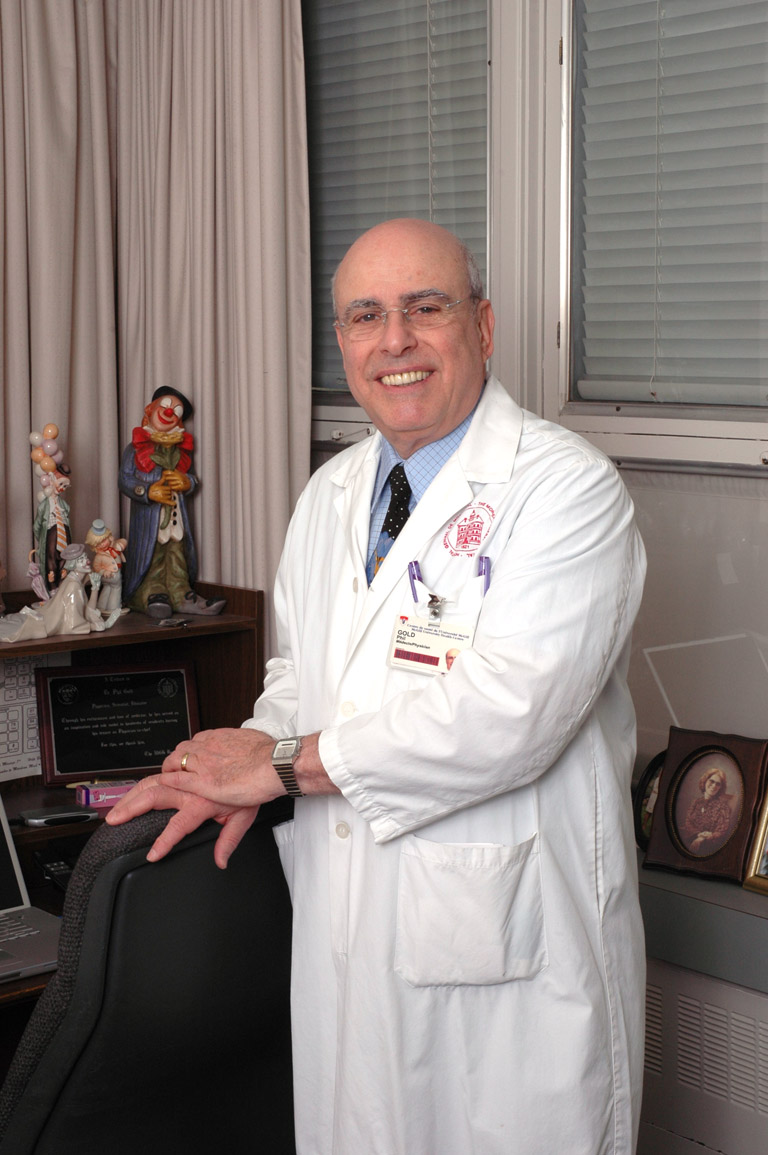

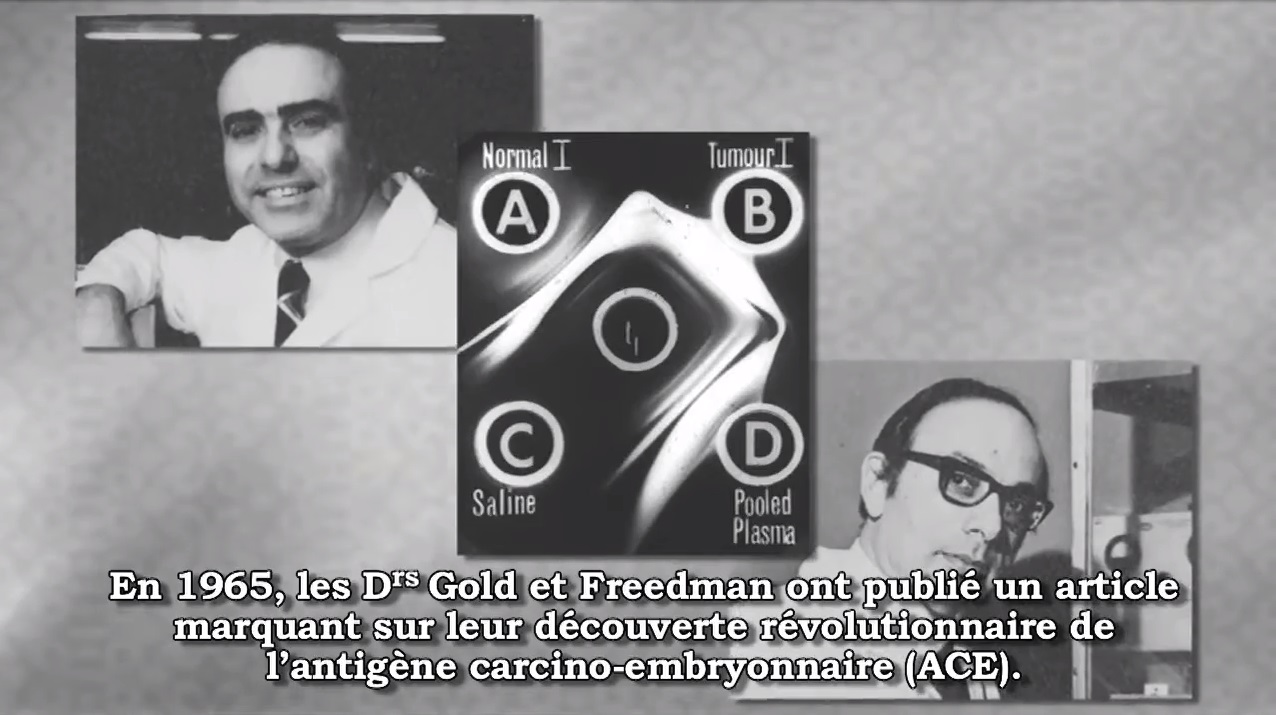

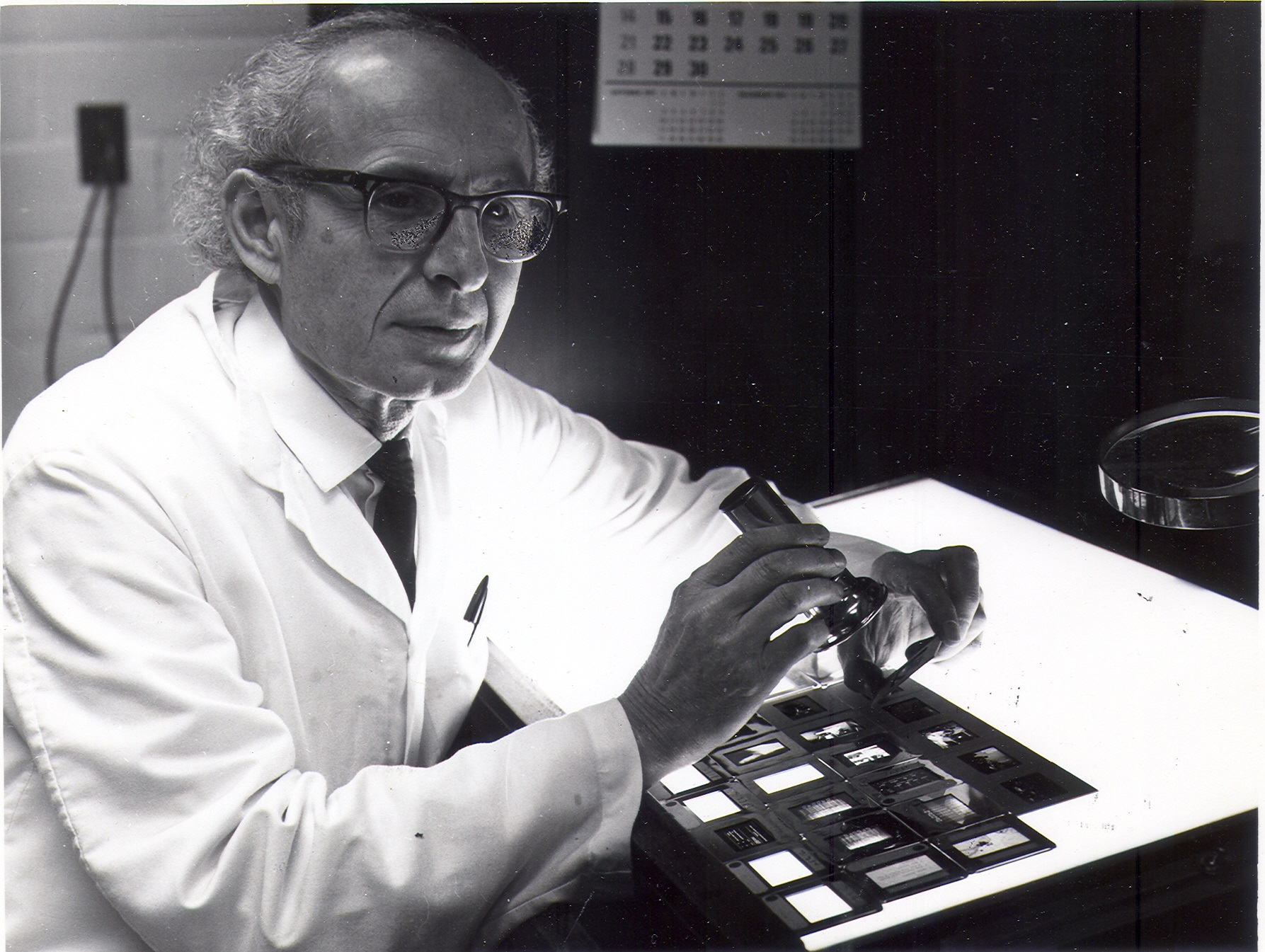

In 1965, after several years of research in the Allergy and Immunology laboratories of the UMC, Phil Gold and Samuel Freedman published a paper that described a new molecule – the Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) – in tissue from large bowel tumours. The discovery was revolutionary: For the first time, it identified a property that could distinguish cancerous cells from non-cancerous cells, leading to the development of a blood test that is still widely used in the management of colon cancer. Gold and Freedman’s work on CEA sparked a revolution in cancer research and made the MGH an authority on tumour-markers. Their research received international recognition, including the prestigious 1978 Gairdner Foundation award.

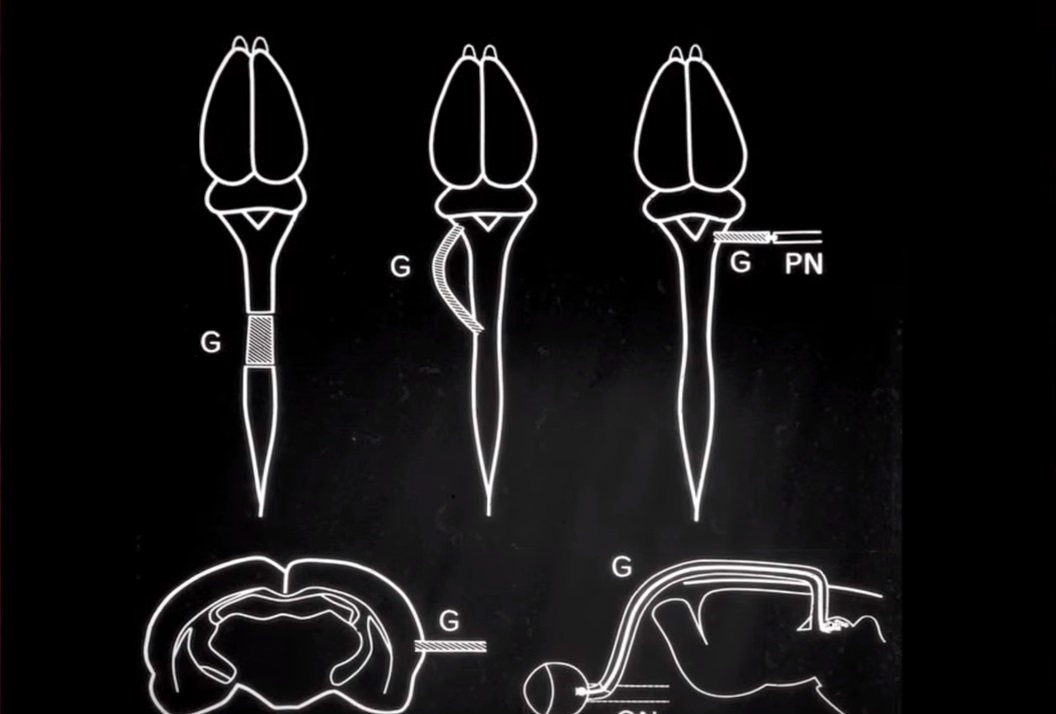

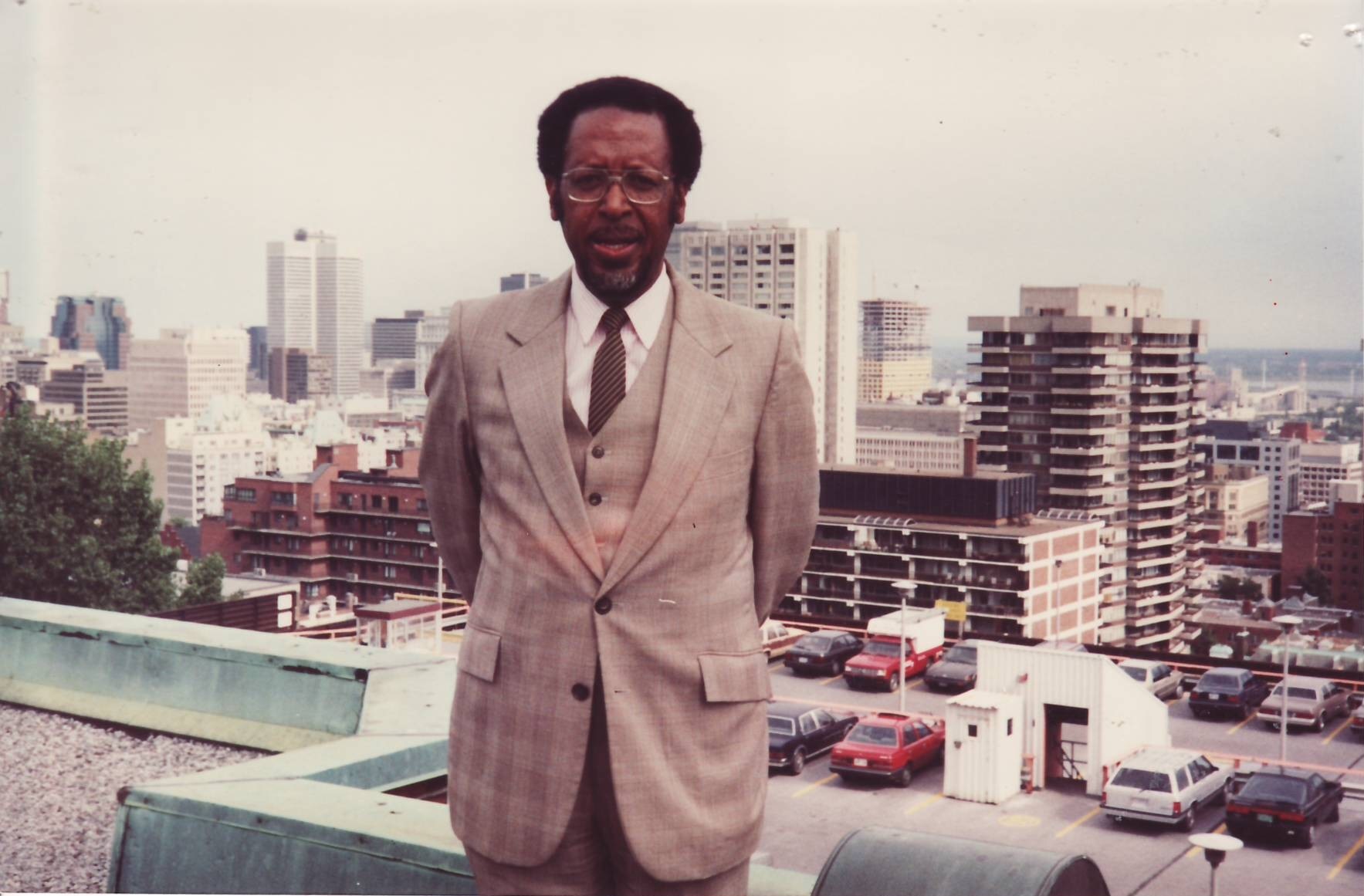

With a team from the MGH Division of Neurology, Albert Aguayo made a paradigm-shifting discovery about the behaviour of injured nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord. After spending years in the 1970s conducting experiments on the behaviour of grafted peripheral nerve cells, Aguayo and his team trained their focus on the central nervous system. At the time, neural regeneration in the brain and spinal cord was considered impossible: nerve fibers, when damaged, were thought to simply die. Aguayo was able to show that nerve fibers could survive – often months after initial injury – and, under the right circumstances, could be conditioned to repair themselves. This discovery had implications for the entire field of neural regeneration.

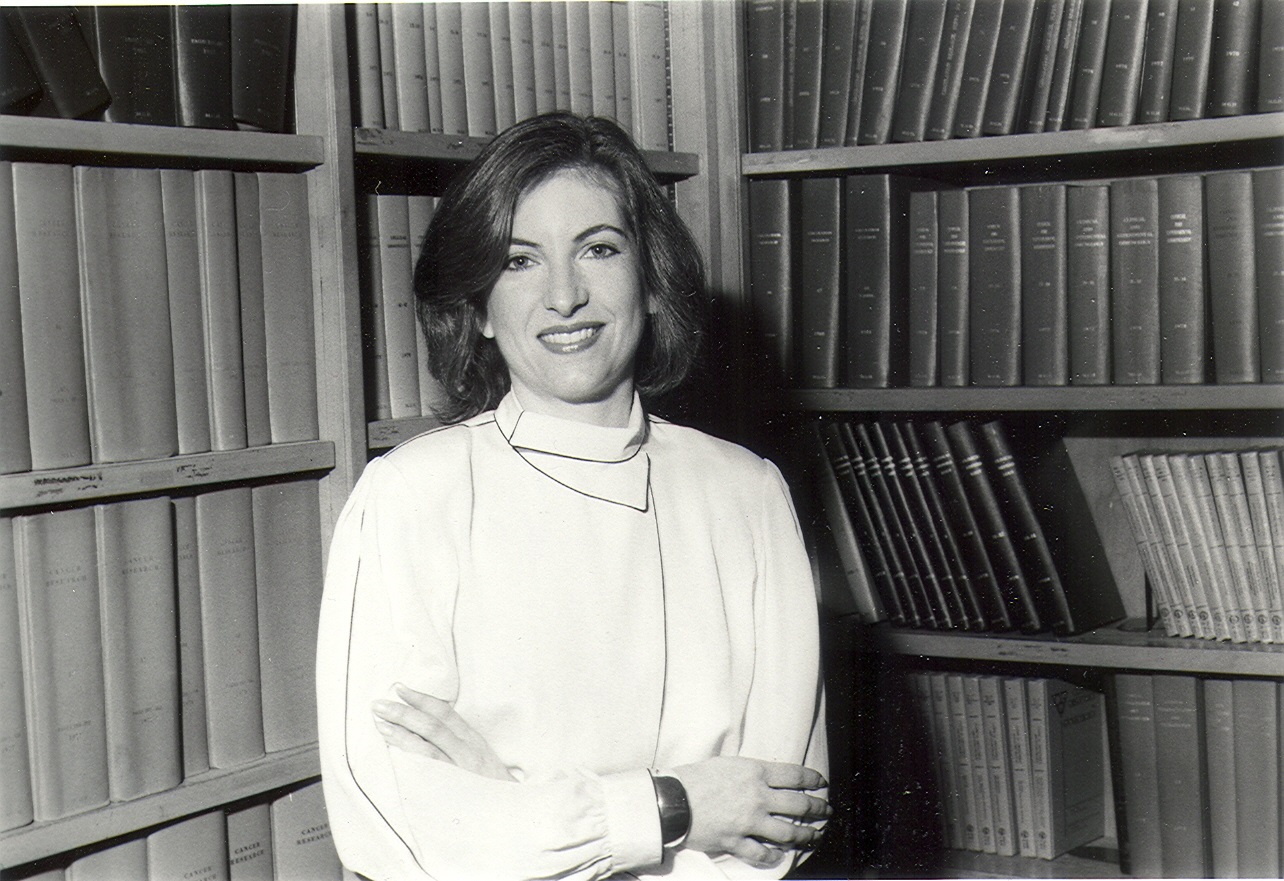

Drs. Ronald Melzack and Mary-Ellen Jeans of the Pain Clinic, 1982. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.933

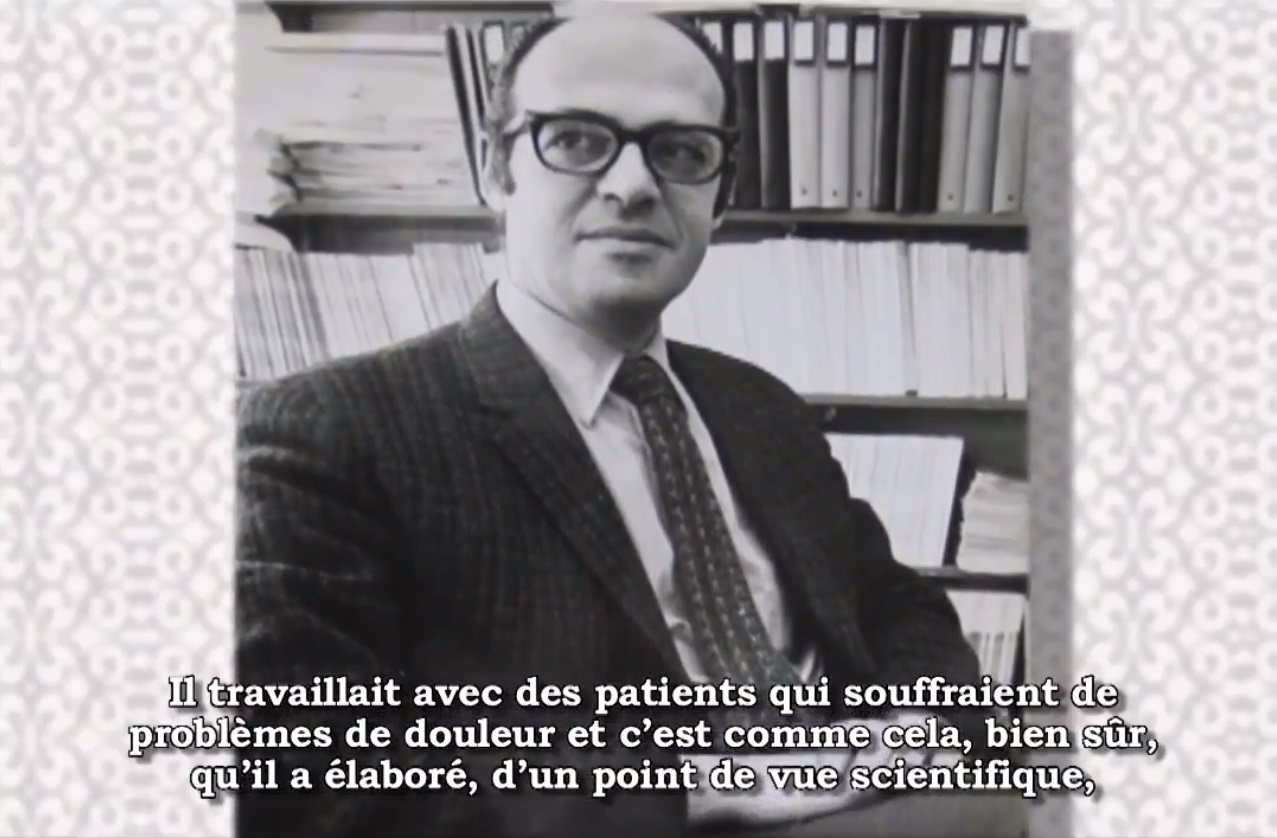

Psychologist Ronald Melzack was a pioneer in pain research and treatment. In 1965, he worked with neurophysiologist Patrick Wall to develop the Gate Control Theory of pain, which paved the way for interdisciplinary research and treatment protocols that address the complex social, psychological, and physiological aspects of pain. In 1974, Melzack teamed up with neurosurgeon Joseph Stratford and nurse Mary Ellen Jeans to establish the first pain clinic in Canada out of the MGH, which earned a reputation as one of the foremost pain treatment services in the world. Recognizing that the trend towards increased specialization led to poor outcomes for patients, the Pain Clinic team consisted of professionals from the fields of neurosurgery, anaesthesiology, psychiatry, biochemistry, nursing, and psychology. Over time, the clinic was renamed the Alan Edwards Pain Management Unit, after Edwards’ generous support. It is now an internationally recognized centre of excellence. In 1975, Melzack developed the McGill Pain Questionnaire, an internationally-adopted clinical tool for measuring pain.

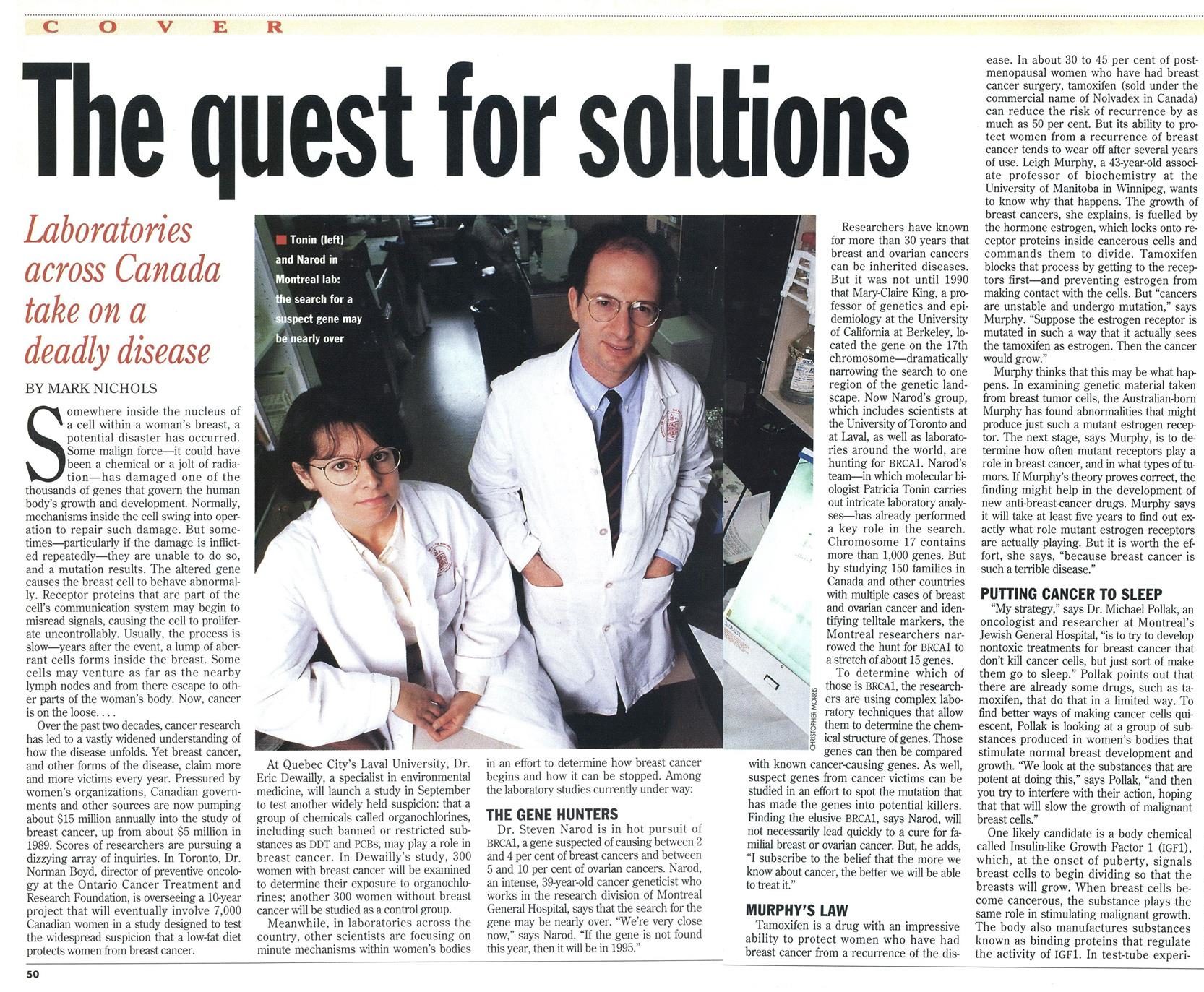

In 1991, Steven Narod became the first physician recruited to the Division of Medical Genetics to conduct research and service in the area of cancer genetics. This was an important turning point for the Division, establishing it as a leader in both Quebec and Canada in the area of hereditary cancer. Patricia Tonin joined Narod in 1993 and they began to search for the gene causing hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. In 1994, they jointly published a paper in Science describing the successful isolation of this gene (BRCA1). They also played an important role in isolating a second gene for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (BRCA2) in 1995-96.

In 1996, Thomas Hudson founded the Montreal Genome Centre. This ushered in the golden era of genomics at McGill, which culminated with the opening of the McGill University Genome Quebec Innovation Centre in 2003, which also doubles as Expertise Centre for Genome Quebec. Hudson has become the best-known Canadian scientist in the area of genomics.

Hudson has focused most of his investigations on the dissection of complex genetic diseases. Ongoing research includes: the search for genes predisposing to lupus, inflammatory bowel disease, coronary artery disease, asthma and diabetes. The laboratory also uses DNA-chip technology to characterize breast and ovarian cancer.

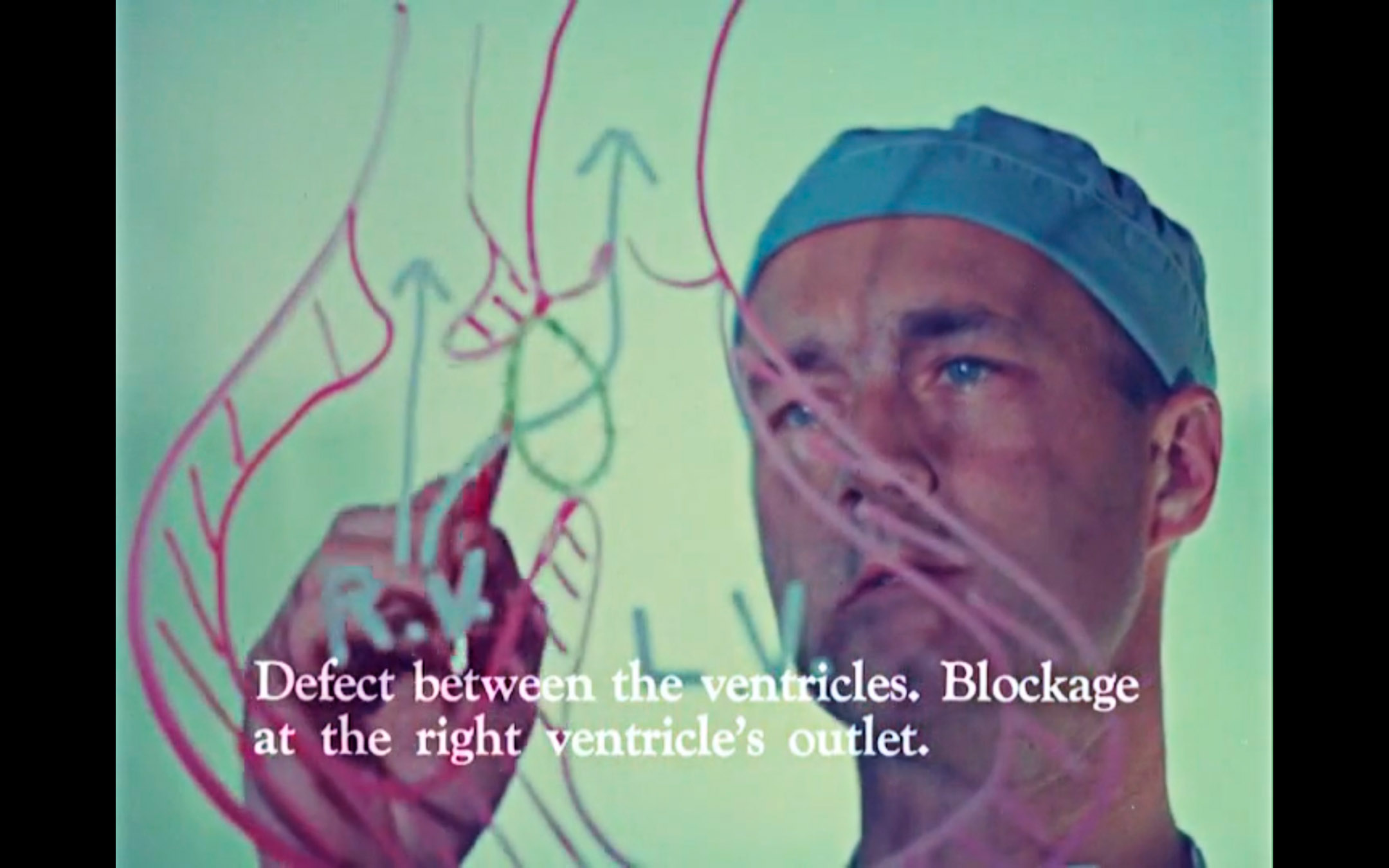

Anthony Dobell was one of the first physicians to perform open-heart surgery in Canada. Though mostly stationed at the Montreal Children’s and Royal Victoria hospitals, in 1960 he made a major contribution to surgery at the MGH by leading the first surgical team to perform in-house open heart surgery. Shortly after his arrival, he established the training program in Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery at McGill University. Over the course of his career he performed more than two thousand heart operations on children.

Dr. Anthony Dobell discussing open heart surgical procedure. Still from Robert Cordier’s Miracles in Modern Medicine, 1967. Library and Archives Canada, 1973-0265, copyright Robert Cordier. Curatorial consultant: Steven Palmer

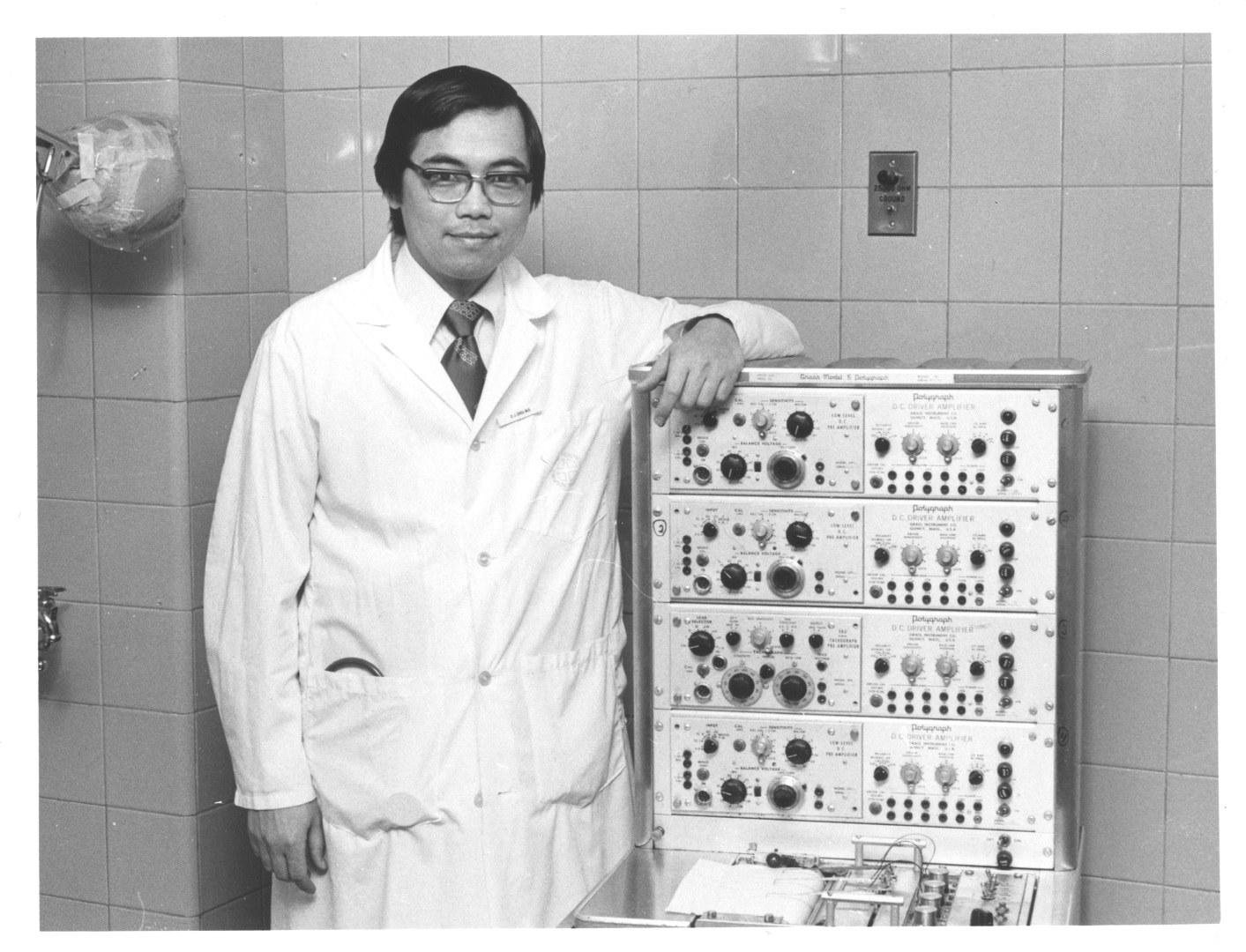

Ray C.J. Chiu was a gifted cardiovascular surgeon whose experiments, conducted at the University Surgical Clinic, led to several important surgical innovations and techniques in the 1980s and ’90s. These include the spiral vena cava graft, retrograde cardioplegia (a method of stopping the heart for cardiac surgical interventions), and stem cell therapy for failing hearts. Chiu also introduced a procedure called dynamic cardiomyoplasty, involving the use of a patient’s back muscle, in conjunction with a special pacemaker, to stimulate and strengthen the contractions of a weak heart. This historic procedure made Chiu the first cardiac surgeon to overcome the physiological barriers presented by the unique behavior of the heart muscle.

Emil Skamene founded the McGill Centre for the Study of Host Resistance in 1988, an important research group operating out of the MGH that has contributed to the developing field of immunogenetics, or the study of the genetic bases of immune responses. His team’s discovery of the gene controlling susceptibility to mycobacteria (which causes diseases such as tuberculosis and leprosy) won Skamene international acclaim. The Centre has since applied these research models to the investigation of genes that contribute to asthma, cancers, diabetes and hypertension.

A world-renowned orthopaedic surgeon, Jo Miller founded the Orthopaedic Research Laboratory of the MGH in 1967, which operated out of the USC. During this time, Miller conducted pioneering work developing techniques and materials related to bone and joint implantation and remodelling, making him a major innovator in the field of arthroplasty. His commercial implant designs were widely adopted by orthopaedic surgeons around the world, most notably the Miller-Galante prosthesis, an artificial knee developed with Jorge Galante.

Carl Arthur Goresky was an internationally renowned scientist, clinician and teacher whose hallmark 1963 paper, using pure mathematical precision, uncovered many aspects of capillary-tissue exchange in the liver. This discovery brought a new understanding to the liver’s transport network, which allows the organ to metabolize and move materials such as glucose, proteins, and vitamins to tissues in the body that need them. Goresky’s understanding of the liver led to studies of other transport systems in the body’s microvasculature, making him a pioneer in the study of transmembrane transport and intracellular metabolism.

Dr. Ken Bentley receiving the CDA Medal of Honour at the CDA Annual Meeting from Dr. Alastair Nicoll. Courtesy of the Canadian Dental Association. Photographed by Mr. Greg Teckles

Kenneth C. Bentley was a gifted teacher, administrator and dental trailblazer, who established the specialty residency training program in oral and maxillofacial surgery at the MGH. He held the positions of both Dental Surgeon-in-Chief (from 1970 to 2000) and Dean of the Faculty of Dentistry (from 1977 to 1988). His leadership skills were recognized when he became the first dentist in Canada to chair the Council of Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists at the MGH in 1988. He retired from McGill in 1998 as Professor Emeritus and was awarded the Canadian Dental Association Medal of Honour in 2016.

H. Bruce Williams was an internationally recognized plastic surgeon known for his pioneering work on microsurgical techniques, which began out of University Surgical Clinic in 1970 and later moved to the Plastic Surgery Laboratory of the MGH Research Institute. He established the MGH Burn Unit and was celebrated for his work in peripheral nerve microsurgery and innovative burn treatment and skin grafting techniques. His surgical work on congenital abnormalities improved the lives of thousands of children and young adults. In 2006 he was granted an honorary award from the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, the highest honour in the field of plastic surgery; and was the only Canadian to be appointed president of the American Association of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

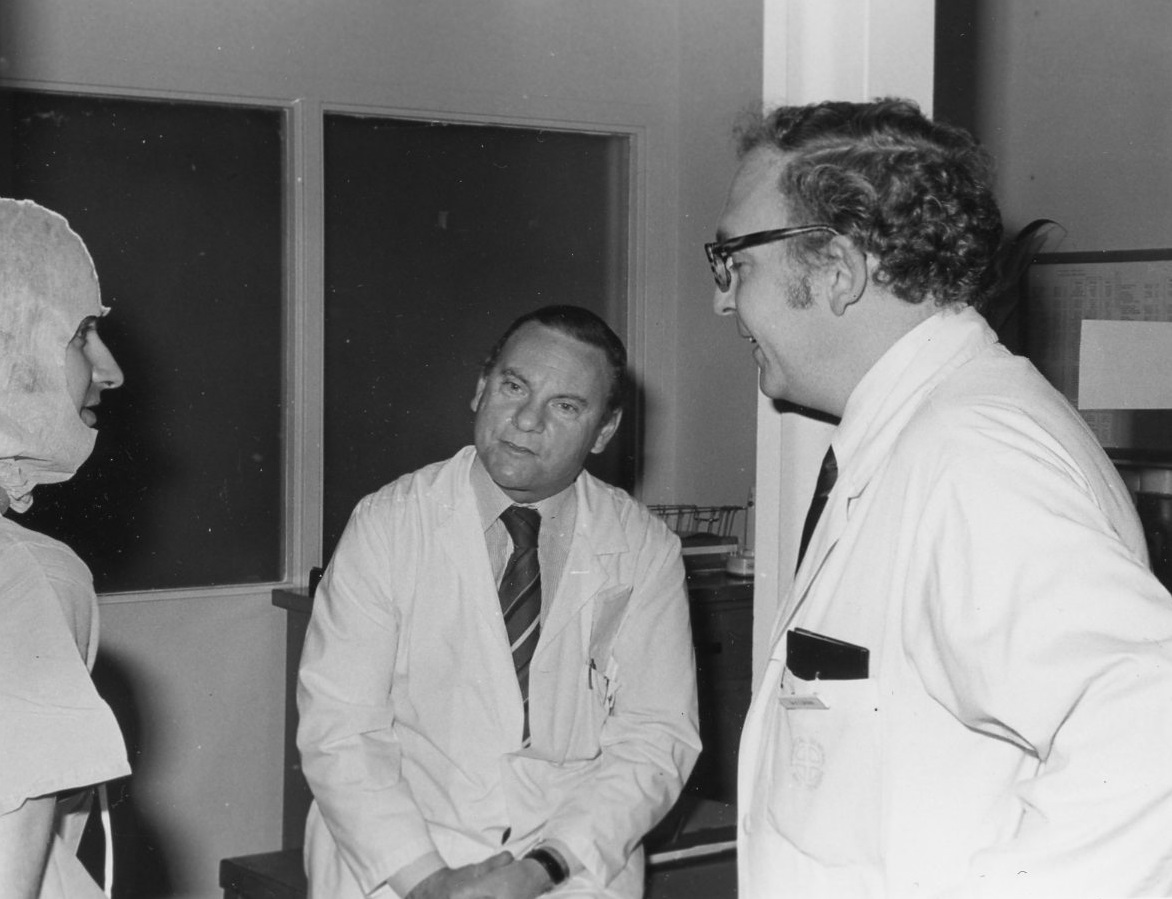

Dr. H. Bruce Williams, centre, with Dr. H.C. Brown, 1977. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.1186

Nursing Achievements

Mary Mathewson was Director of Nursing from 1946 to 1953. Her mastery as an administrator and her firm yet gentle approach allowed the School to flourish through the difficult post-war years. With the ever increasing difficulties at the old site she was instrumental in the plans for the new hospital – a dream she unfortunately did not live to see. Her dedication to nursing is captured in the 1947 book she co-authored with John Murray Gibbon, Three Centuries of Canadian Nursing – the first written history of Canadian nursing.

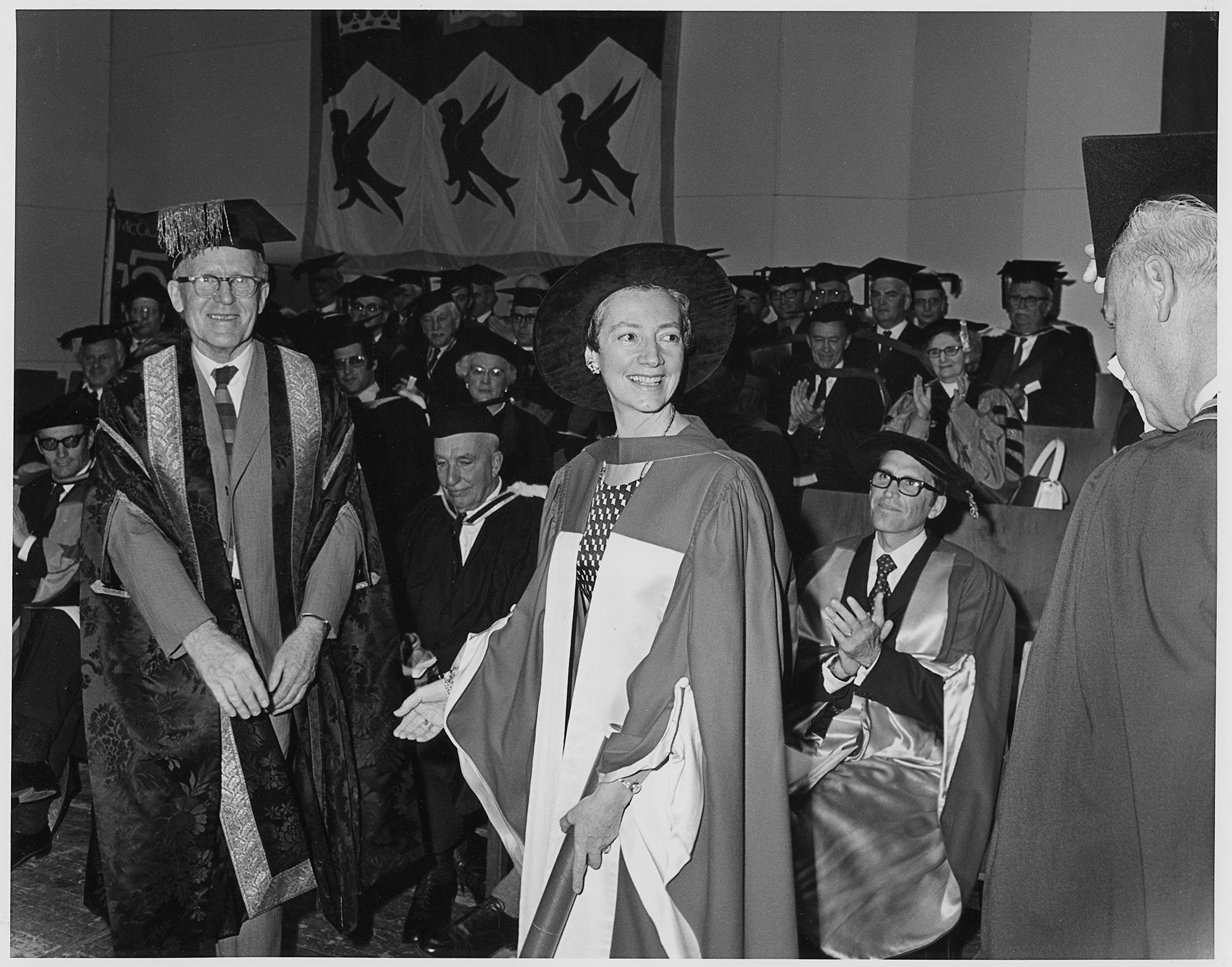

An outsider to the MGH who quickly won the hearts and respect of staff and students, Isobel MacLeod was Director of Nursing from 1953 to 1975 and Principal of the MGH School of Nursing in its final years. MacLeod encouraged innovative learning within the hospital school and paved the way for the study of nursing to move into the CEGEP system. MacLeod was granted an honorary doctorate from McGill University in 1972 in honour of the MGH School of Nursing’s prominence in Canada and the world. She won the MGH Award of Merit in 1994 and the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal in 2002.

Isobel MacLeod receiving her honorary doctorate from McGill, 1972. Archives of the Alumnae Association of the Montreal General Hospital School of Nursing

As Director of Nursing from 1975 to 1983, Helen Taylor supported the evolution of professional practice at the MGH by introducing primary nursing. With leadership roles in various professional organizations, Taylor also contributed to the development of nursing in Quebec and Canada. She was the first nurse appointed Chair of the board of Accreditation Canada (1977-78), and the first Canadian president of the Commonwealth Nurses Federation (1980-84).

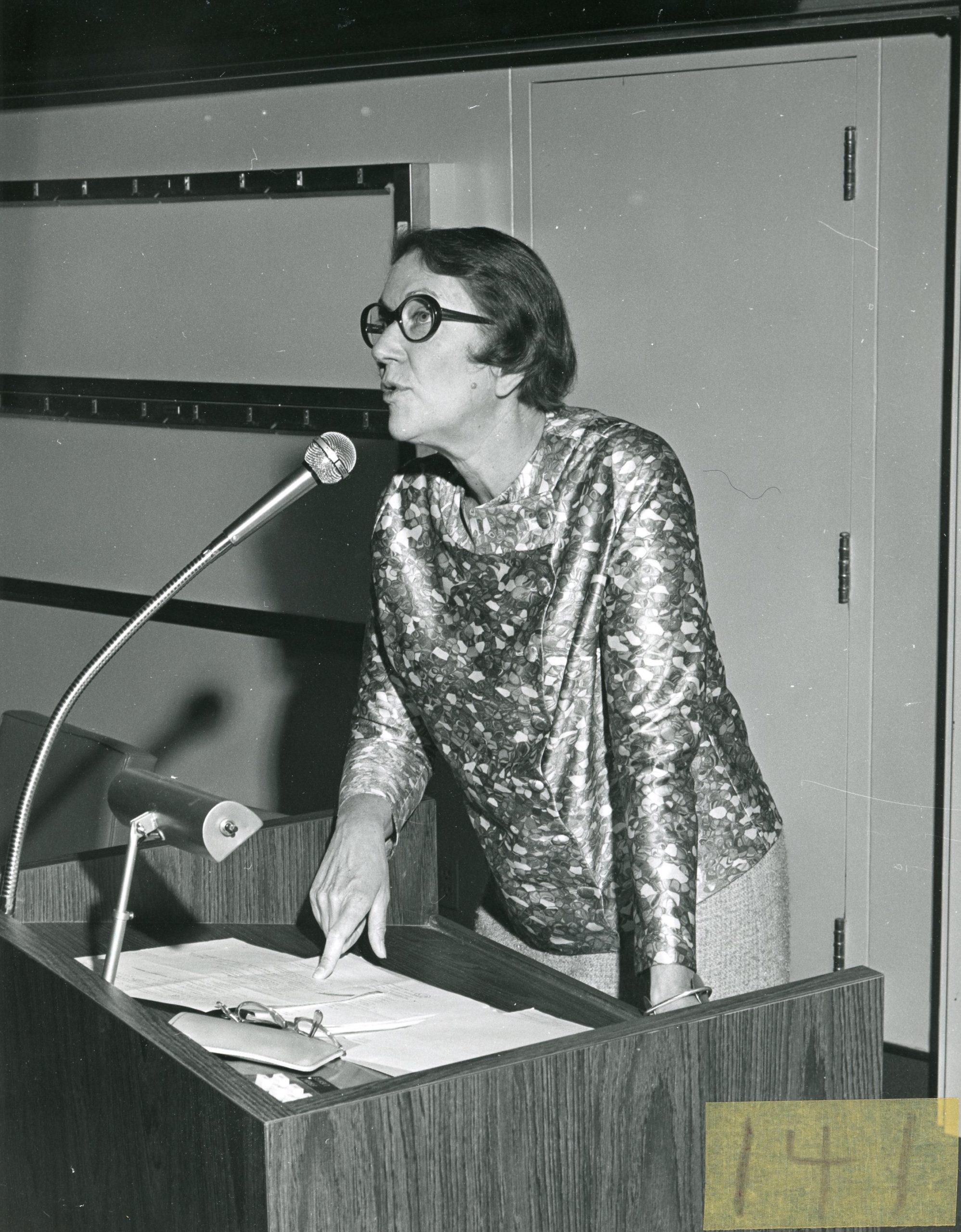

F. Moyra Allen, an MGH graduate, was an esteemed nursing educator and researcher. In 1969, she founded the first Canadian scholarly nursing journal, Nursing Papers (now called the Canadian Journal of Nursing Research). In 1973, she won the National Health Scientist Award, which she held for nine years. In 1974, she established a research unit in nursing and health care at McGill – the only one of its kind in a university school – and used the MGH Family Medicine Unit as one of its practice sites. Allen was responsible for creating the first master’s entry course to nursing in Canada at McGill. The Canadian Nurses Association gave her the Jeanne Mance Medal in 1983. The same year, she was awarded the Insigne du Mérite from the Order of Nurses in Quebec, and received honorary doctorates from McMaster University and the Université de Montréal in 1984 and 1990, respectively. In 1987, she became an officer of the Order of Canada.

Valerie Shannon accepting the Insigne du Mérite from the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Quebec, 1997. Courtesy archives of the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Quebec

Valerie Shannon was Director of Nursing from 1984 to 1998, as well as co-founder, chair and first president of the Canadian Council of Cardiovascular Nurses (1973-74). In 2008, she became the first woman to become president of the MGH Corporation, a position she held until 2016. With the support of the MGH Foundation, Shannon established a department of nursing research in 1985 under the leadership of Sara R. Frisch – a first for a Canadian teaching hospital. She created the role of nurse scientist in a hospital setting, which was first held by Mary Grossman (1993). Shannon oversaw the implementation of case management for complex patients, which resulted in the publication of a book by Claire Thibault and Michele Nadon in collaboration with the Ordre des infirmières et infirmiers du Québec (OIIQ) titled « Suivi systematique de clienteles – expériences d’infirmières et recencion des écrits ». This laid the groundwork for the infirmière pivot role today across the province. Shannon was awarded the Insigne du Mérite from the OIIQ in 1997, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy of Canadian Executive Nurses in 2003, and the MGH Award of Merit in 2005.

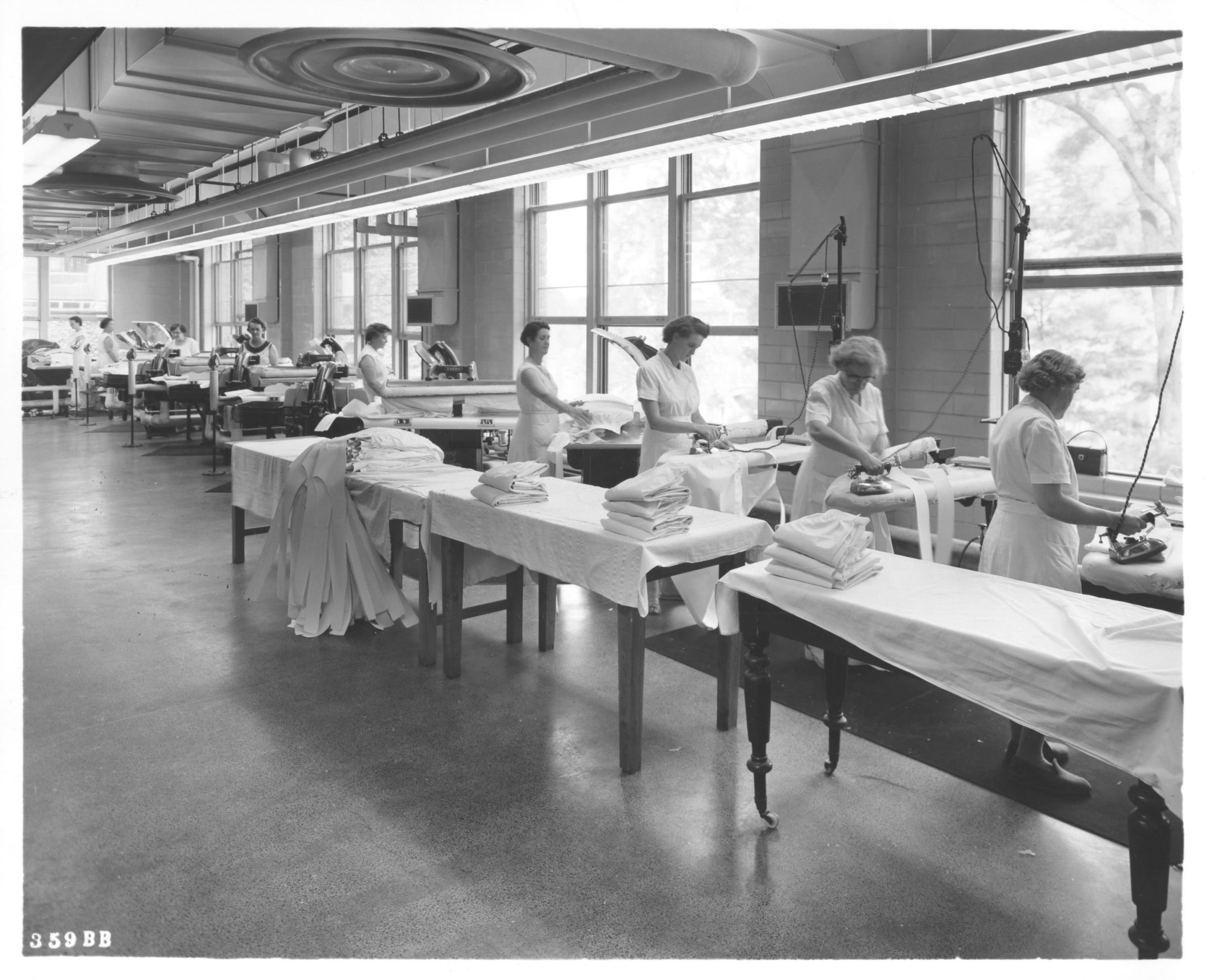

Women’s voluntary efforts became increasingly organized during WWII. In the case of The Women’s Auxiliary of the MGH (now simply The Auxiliary), these efforts evolved into a permanent initiative at the hospital, operating through networks of industrious women who felt there was still work to be done when the war ended.

Helen Hutchison established The Auxiliary in 1949, canvassing the Women’s Canadian Club to establish a membership base of over 1,711 women in its first year of operation. The Auxiliary’s main goal was to promote the welfare of the hospital and its patients through volunteer service, fundraising and community outreach

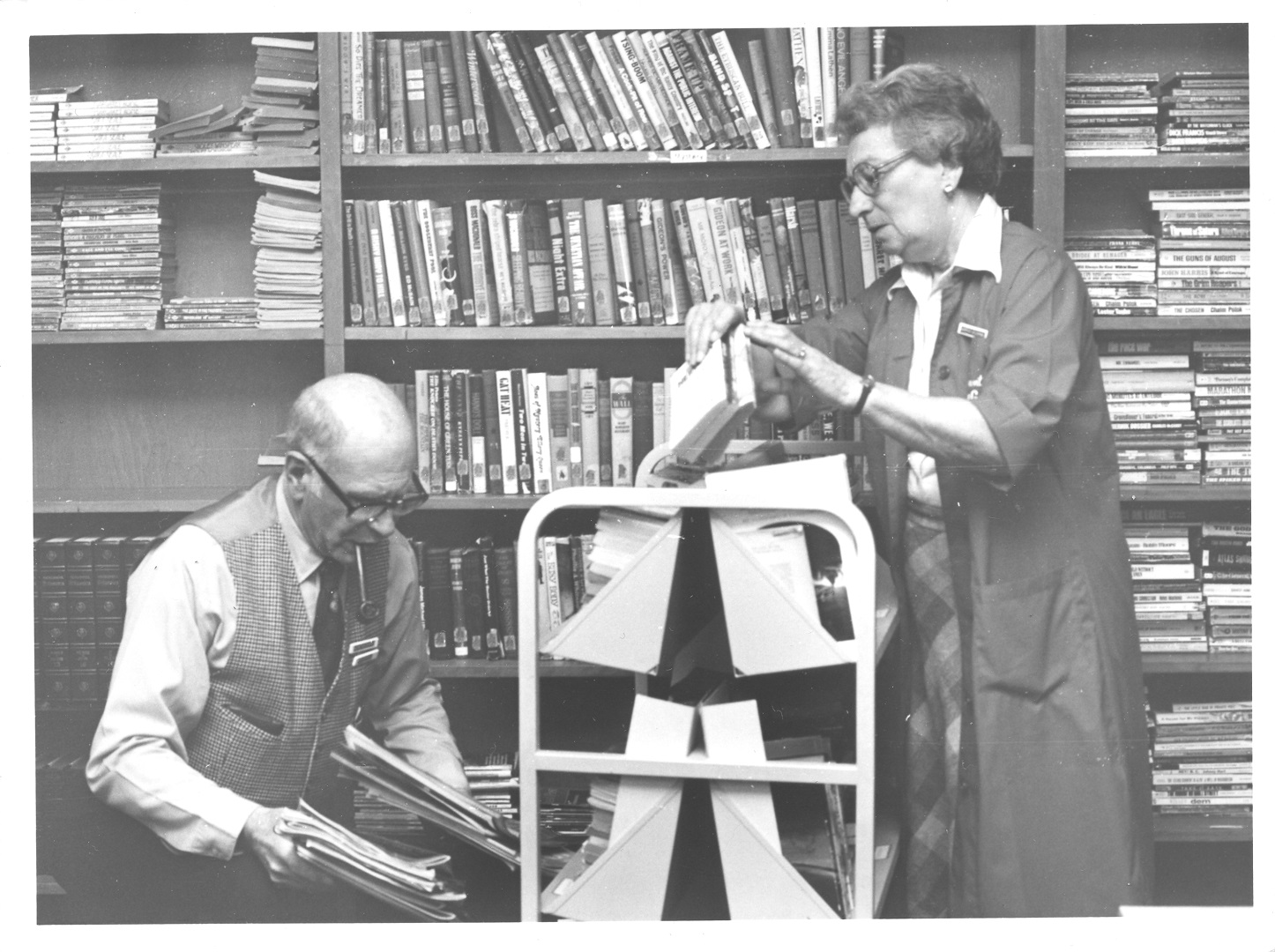

Volunteers at the Patients’ Library, 1978. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.1236

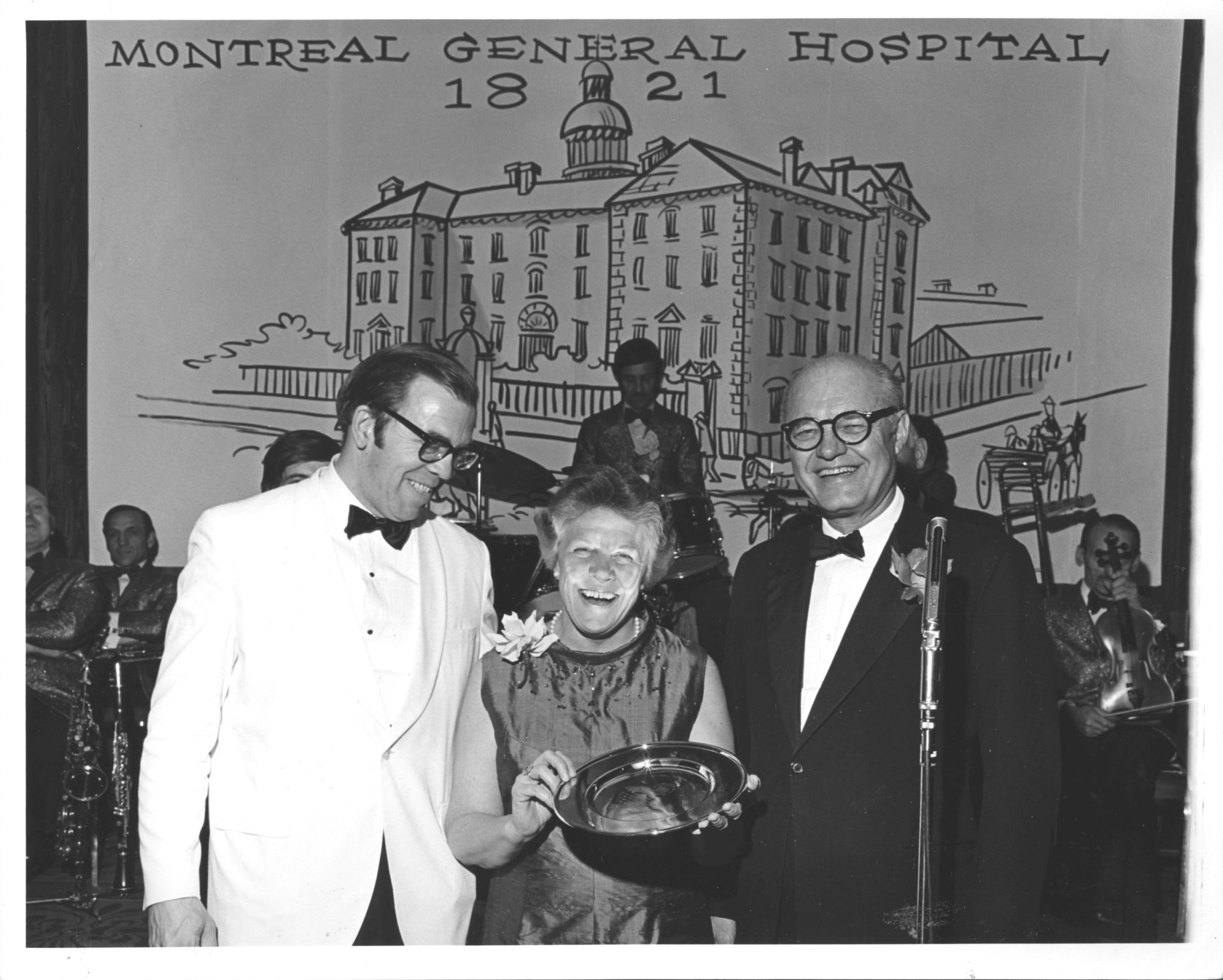

Whitley was president of The Auxiliary from 1957 to 1960. In 1969, she became the first woman to serve on the Board of Management of the MGH – an indication of her status as a key player in the administration. She received an honorary doctorate from McGill in 1992.

L-R: Dr. Ross Hill, Barbara Whitley, and the Hon. Miller Hyde, at celebrations for the 150th anniversary of the MGH, 1971. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.222

At first, volunteers visited patients, ran a lending library, and wheeled a travel wagon filled with sundries around the hospital. Eventually, with the creation of a separate volunteer department in 1979, there came to be over fifty different patient support programs at the hospital.

Through revenues generated by fundraising activities and their Memorial Fund, The Auxiliary has contributed substantial financial resources to the hospital. When the administration reached a decision to move sites, Hutchison raised the first $25,000 for the construction of a new hospital. Since then, several millions of dollars have been raised for equipment, patient care and research.

From the 1950 opening of the first gift shop and snack bar in a cupboard at the Western Division, The Auxiliary has become known for its creative fundraising initiatives, such as their Hospitality Corner and Coffee Shop, Early Bird sale, annual dinner dance, catering service, Book Nook, beauty salon, and fashion shows.

From 2008-2019, when data was formally collected, 570,031 volunteer hours were recorded, the equivalent of 339 full time staff members.

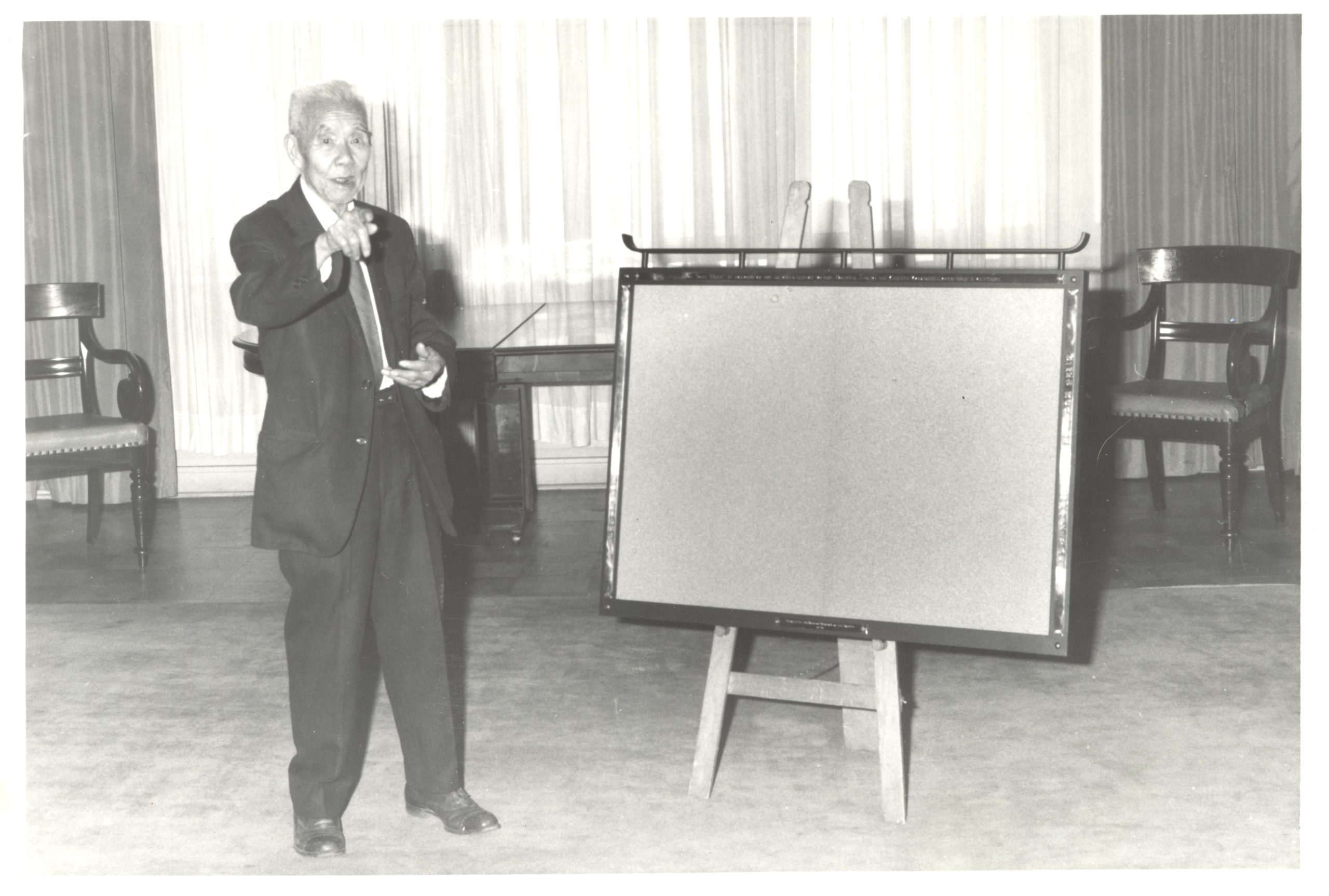

Tom Hum

Tom Hum was a Chinese-Canadian who volunteered his time to act as an interpreter (and self-appointed advisor) for Chinese patients visiting the MGH outpatient department. He ran a grocery store in Chinatown and would make deliveries on a horse-drawn carriage, transporting anyone that needed medical attention to the old MGH on nearby Dorchester street, and staying with them to act as interpreter until they were released. When the MGH moved to its current location, he followed, continuing his tradition of generous service. After his retirement he continued to spend every day at the hospital. He also held annual fundraising dinners for the Chinese community in support of the hospital.

The MGH celebrated Tom in a ceremony in 1976, in which they presented a tribute: a wrought-iron notice board with brass engravings, with an inscription in English and Chinese that read: To Tom Hum: In honour of his devoted service to this Hospital and the Chinese Community of Montreal over half a century – erected by the Board of Directors of the Hospital – 1976.”

As the Quiet Revolution swept the province of Quebec, social and cultural changes were matched by legislative reforms that radically transformed the hospital’s environment. Educational reforms following the Parent Report led to the closure of hospital nursing schools in 1972; changing concepts of health led to increased roles for allied health professionals and created a need for multidisciplinary approaches to care; and the movement around women’s reproductive freedom led to the introduction of birth control and access to therapeutic abortions. The most drastic change affecting the hospital, however, was legislation around the concept of universal access to healthcare, which created the public system we recognize today.

Education Reform and the Rise of the Multidisciplinary Team

The closure of the nursing school in 1972 marked the beginning of the end of the homegrown culture that had been a feature of nursing since Livingston opened the school in 1890. From its inception, a total of 4,275 nurses passed through its curriculum and received certification. The School closed following the release of the five-volume Parent Report (1963-66), which recommended transferring nursing education to the CEGEP system.

As the complexity of patient care increased, McGill University initiated advanced degree programs in Nursing (1944), Social Work (1945), Audiology and Speech Language Pathology (1963) and a Bachelor’s program in Physical and Occupational Therapy (1954). The increased demand for postgraduate education was part of a larger trend in demanding higher education on behalf of the post-WWII generation, and led to increased numbers of graduates and postgraduates in the hospital.

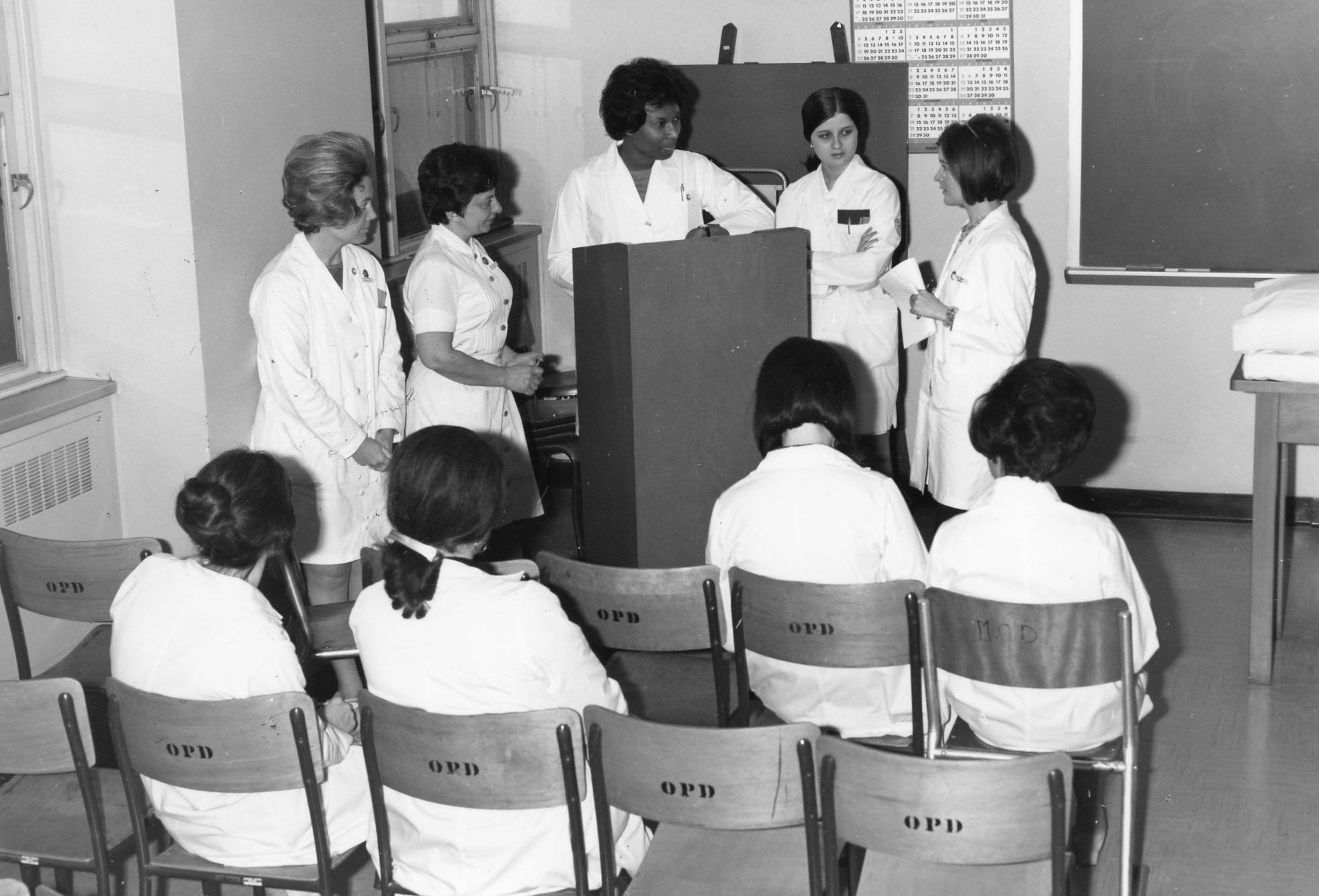

Training of dietetic interns, c. 1970. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.895

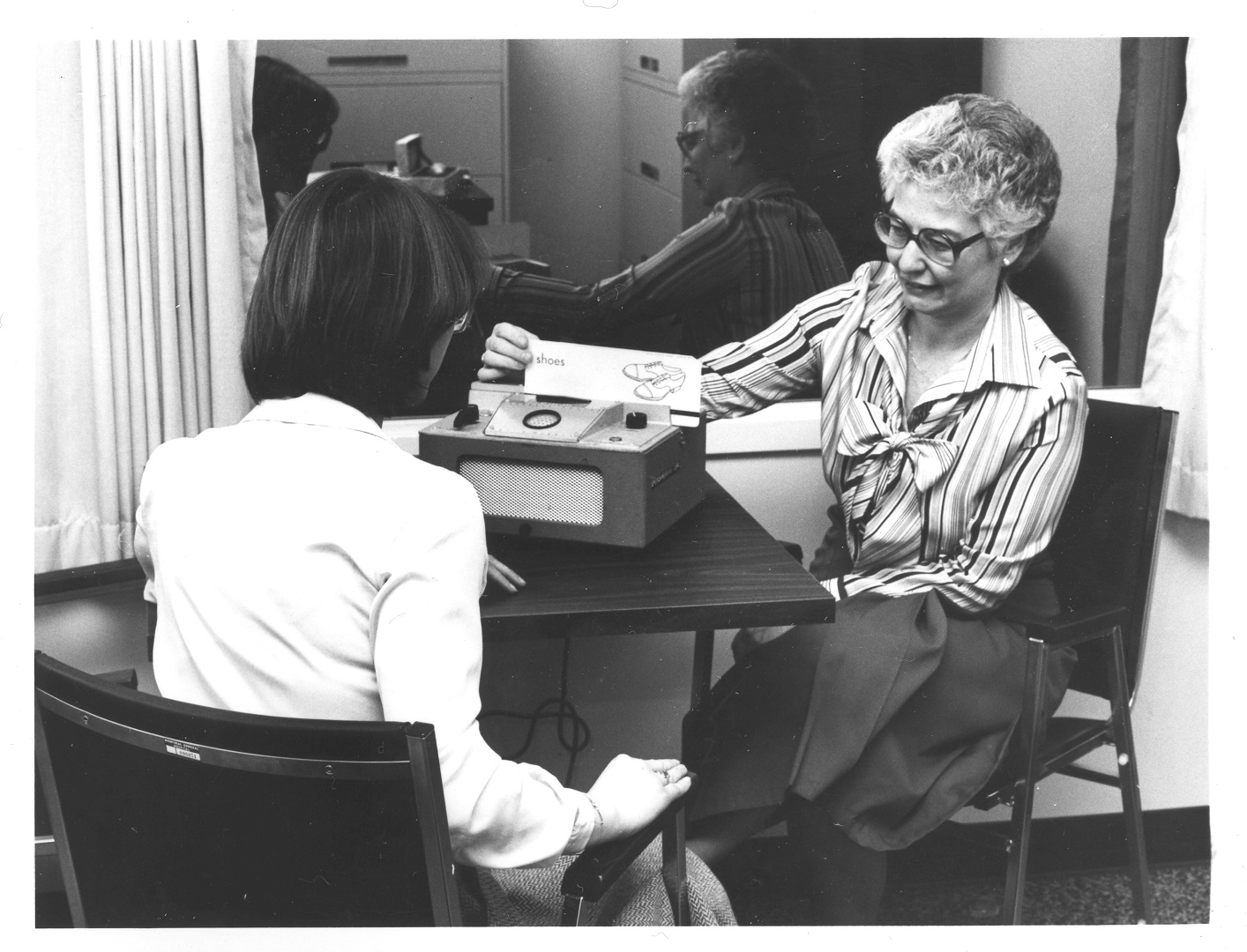

In 1989, Chan received the Eve Kassirer Award for Outstanding Professional Achievement, the highest award bestowed by the Canadian Association of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists, for her contributions to the development of speech-language pathology and audiology in Canada.

Nancy Turner Chan, Speech Therapy and Audiology, 1979. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.1067

The growth of allied health and specialty disciplines – and the knowledge explosion accompanying it – led to the creation of multidisciplinary teams that shaped the treatment plans of patients. Participation between various allied health professions, nurses, and specialists would become essential to the provision of comprehensive patient- and family-focused care. This new way of addressing patient needs became a staple of the quality movement in healthcare, and was based on a revised concept of health surrounding the provincial government’s healthcare reforms.

The Pain Centre, the first of its kind in Canada, brought a multidisciplinary focus to the treatment of chronic pain, with a team consisting of specialists in anesthesiology, neurosurgery, psychology, psychiatry, nursing, physiotherapy, and social work.

Drs. Ronald Melzack, Joseph Stratford, and Mary Ellen Jeans, with clinicians and staff of the pain centre, 1970s. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.933

Unionization

During and after WWII, the union movement expanded in Quebec due to job shortages and the 1944 Labour Relations Act. In the 1950s, unions were strong critics of the conservative Duplessis government and are thought to have had a major influence on the Quiet Revolution.

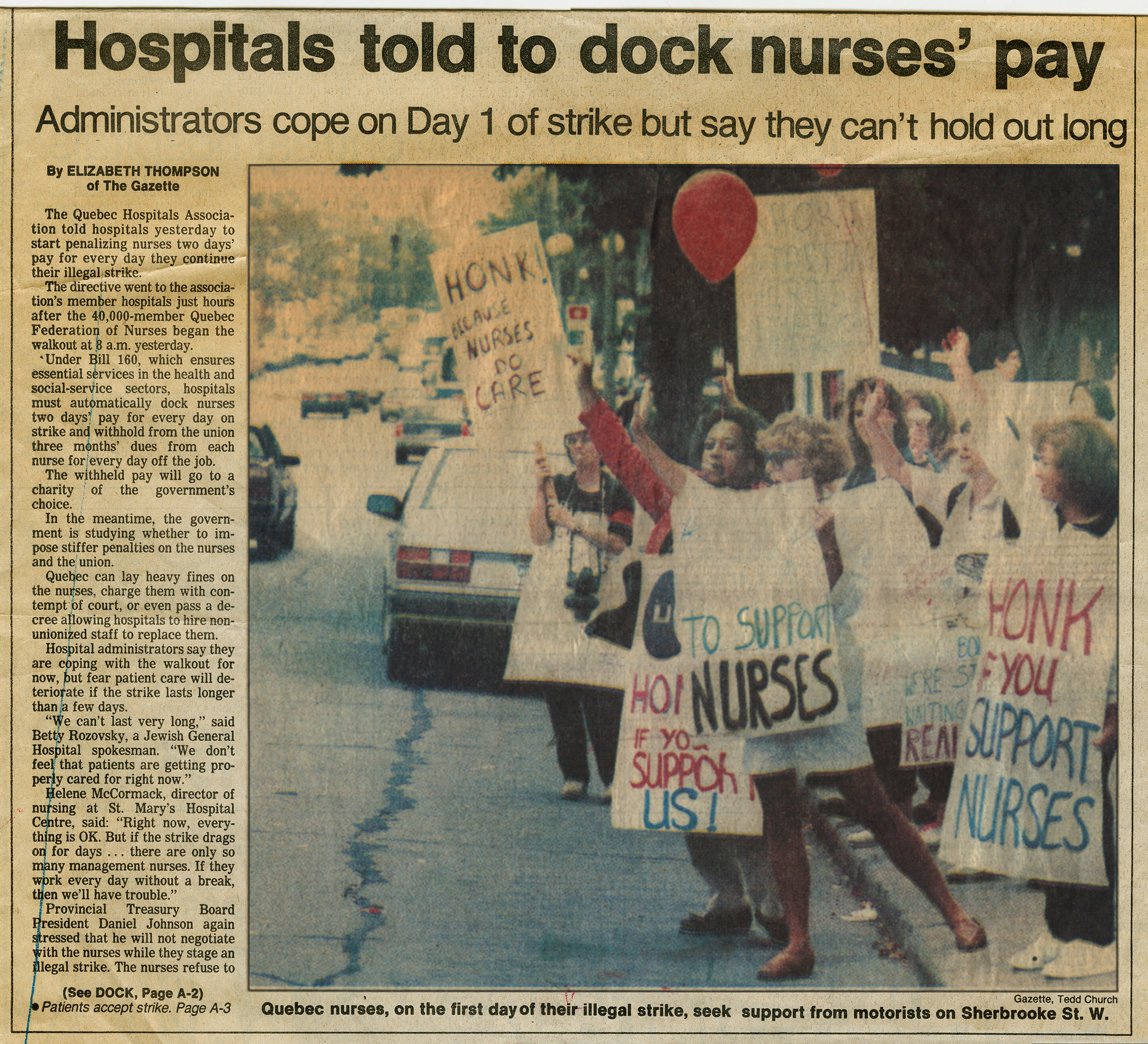

In 1964, the Quebec government enacted a Labour Code that granted the right to bargain and strike to civil servants, teachers and hospital workers. The latter group, however, were usually penalized unfairly compared to other public sector employees – as was the case with the 1972 Common Front strike, and the nursing strike of 1989.

Support workers in English-speaking hospitals first organized a strike action in 1966, the same year as the certification of United Nurses of Montreal – led by president and co-founder Moyra Allen, an MGH graduate. Although United Nurses was Montreal’s first union for English-speaking nurses, Francophone nurses had unionized as early as 1946.

In the nursing field, increased opportunities for occupational advancement combined with effective province-wide organizing to create a professional body of nurses that were highly skilled, aware of their value within the healthcare system, and vocal about their expectations when it came to negotiating better working conditions. Conflicts between the government and the nursing unions led to strikes in 1975, 1989, and 1999. Nurses in 1989 faced harsh penalties for striking due to the Essential Services Act (Bill 160), though they received public sympathy and acted as spokespeople for patients, pointing to the connection between cutbacks, shortages and hospital stay-related complications.

Reproductive Health

In 1968, the hospital opened the Family Planning Clinic, in response to the lack of sex education in the general population and the social momentum of the women’s movement. The Clinic provided birth control information to married and unmarried women and their families, and addressed problems related to unwanted pregnancy, illegal abortion, and illegitimate childbirth, as the public debate around abortion rights peaked after federal decriminalization in 1969.

Community Health Department, Planned Parenthood display, 1977. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.858

In 1969 the federal government passed the Omnibus Bill decriminalizing therapeutic abortion in all provinces, which were to be granted on a case-by-case basis following the recommendation of Therapeutic Abortion Committees (TACs). Because abortion remained illegal, it was up to each TAC’s discretion to define what constituted a threat to a patient’s health necessitating abortion. This created a situation in which access to abortion was unequally distributed across the province – many hospitals refused to set up TACs and categorically refused abortion requests.

At the MGH, the department of Obstetrics and Gynecology established a unified position on abortion. Their core philosophy involved an interpretation of health “as defined by the WHO – as emotional, social, and physical health.” They argued that women’s requests for abortion should be taken at face value rather than subjected to the interview process of the TACs, whose judgments upheld “tremendous inequities” based on personal bias and class-based prejudice. The department’s progressive stance saw them providing 80% of abortions in the province in the first several years following legislation, a majority they upheld for over a decade.

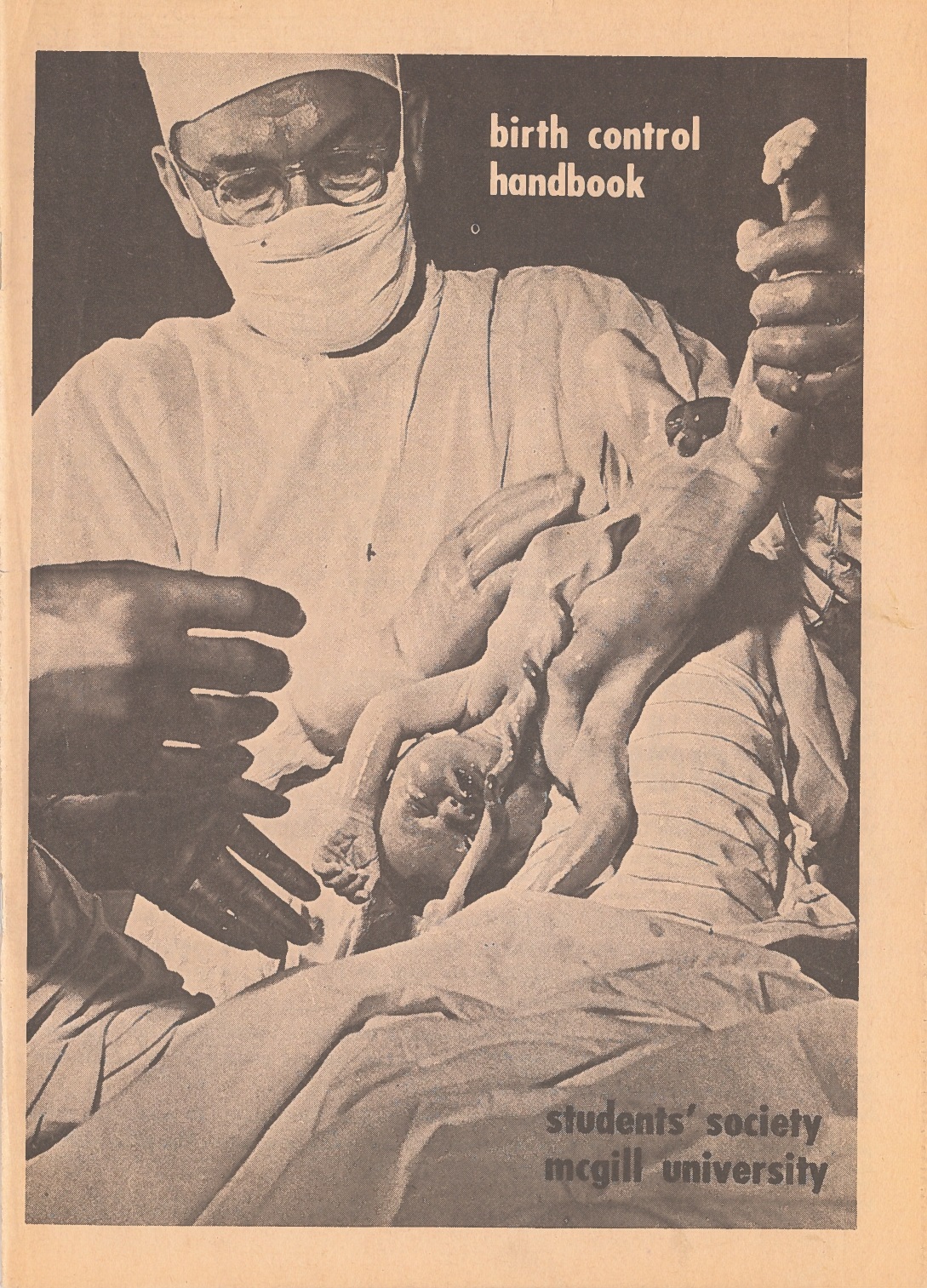

MGH OBGYN Dr. Robert Kinch provided consultation for the birth control handbook, which predated Our Bodies, Ourselves by two years, making it one of the first manuals on modern female reproductive health ever published. It sold millions of copies in North America. As head of the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Dr. Kinch was outspoken in his support of women’s reproductive rights.

Cover of the first edition of the birth control handbook, published by the Student’s Society of McGill University in 1968. McGill University Archives.

A New Disease Emerges:

The MGH and the AIDS Crisis

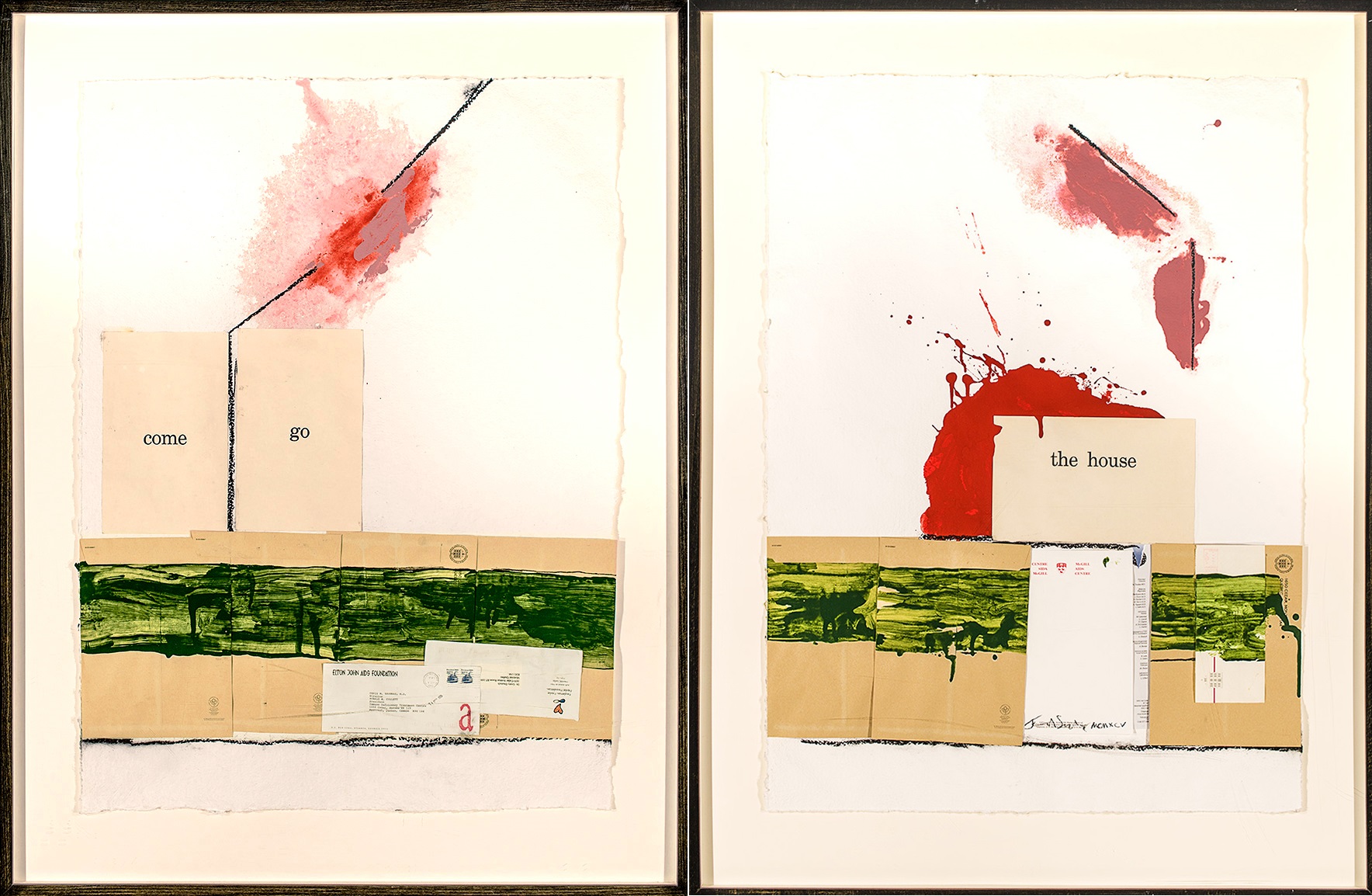

Centrifuge, a diptych created in 1995 by Montreal-based artist John A. Schweitzer, LLD, OSA, RCA, was commissioned on the occasion of the inauguration of the Immune Deficiency Treatment Centre by Drs. Christos Tsoukas and Gretty Deutsch.

As the title implies, Schweitzer’s collage incorporates found ephemera that alludes to the HIV/AIDS treatment centre, or “house,” as a veritable “centrifugal” refuge to those tragically afflicted with the then-fatal disease. Happily, successful drug therapies introduced in subsequent years led to the medical conclusion that a HIV/AIDS diagnosis is now a treatable chronic illness. This projected hope for a cure is reflected in Schweitzer’s binary prescription on the left panel: two flash cards that read “come” and “go”.

John A. Schweitzer, LLD, OSA, RCA, Centrifuge (diptych), 1995, collage on paper. Collection of the Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC.

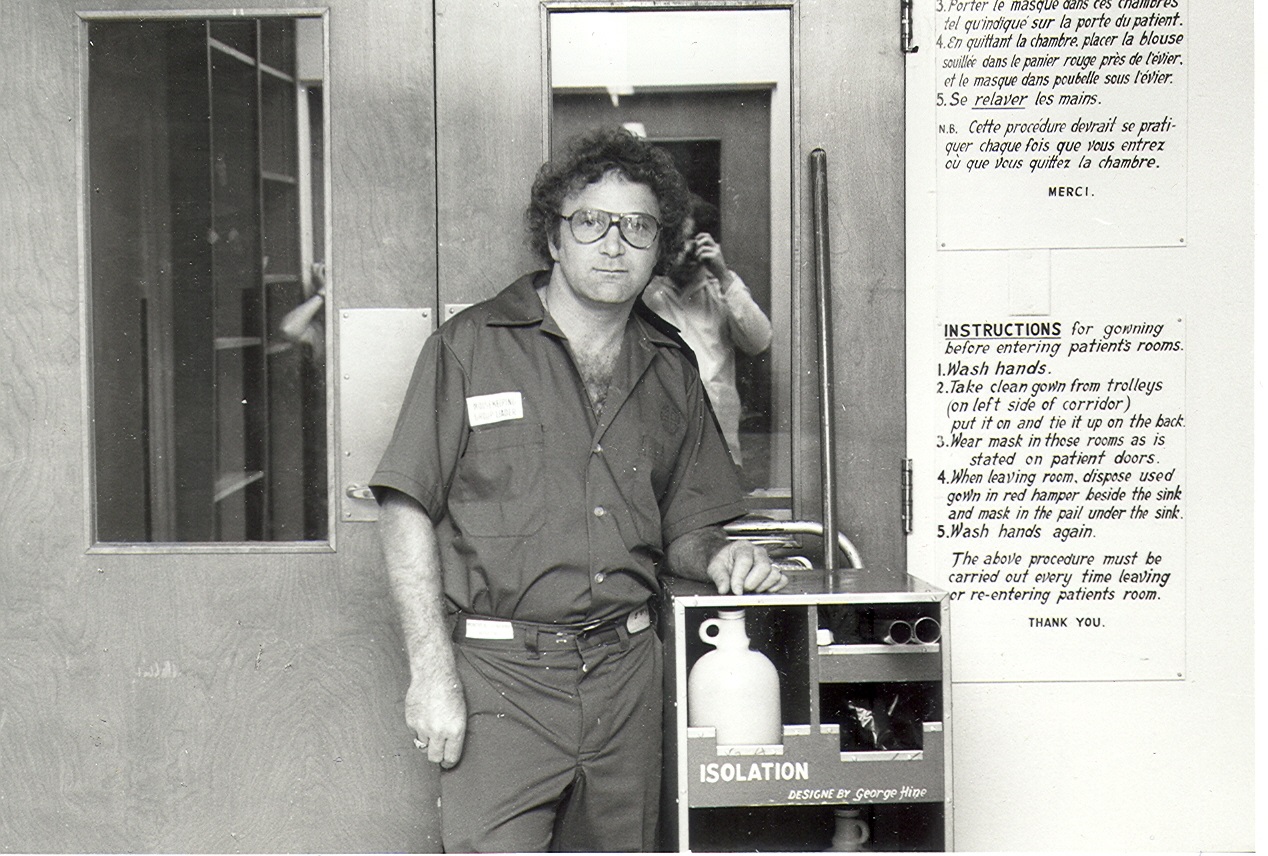

In late 1985, as the AIDS epidemic spread globally at increasingly alarming rates, the MGH opened a clinic dedicated exclusively to the care of AIDS patients, directed by Dr. Christos Tsoukas. The AIDS Clinic – later renamed the Immune Deficiency Treatment Centre – was the first of its kind in Canada, bringing together immunologists, psychiatrists, infectious disease specialists, dermatologists, and other professionals. In addition to multidisciplinary treatment, the clinic provided counselling to patients and their families, performed diagnostic testing, and collaborated on awareness-raising campaigns.

Tsoukas identified the first case of transfusion-related AIDS transmission in Canada and, through his studies on hemophiliacs, was instrumental in the establishment of blood safety protocols outlined in the Krever report.

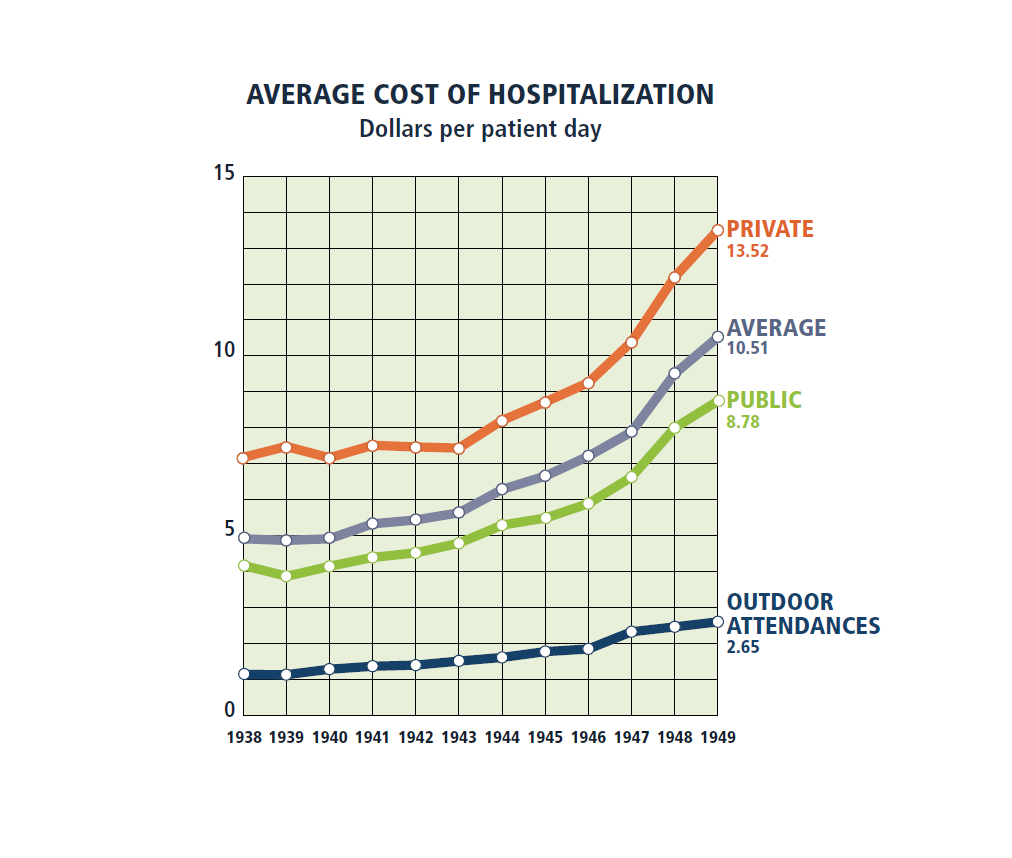

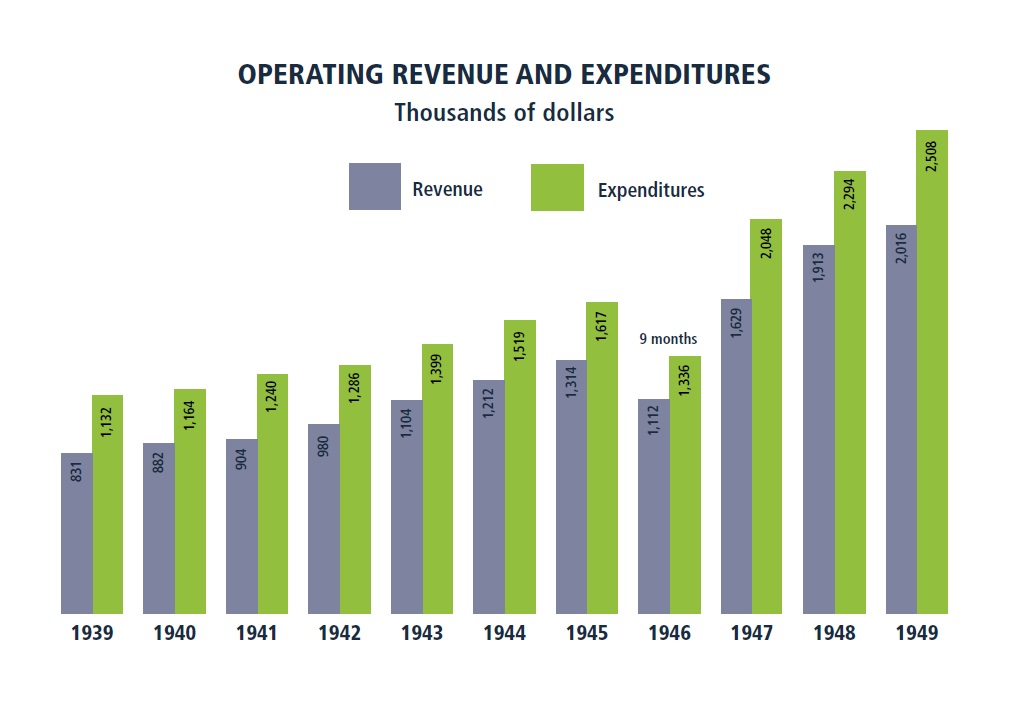

Access to Healthcare: A Human Right

The chart on the left represents the cost, for the hospital, of the various levels of inpatient and outpatient care offered at the hospital as of 1949. The graph on the right clearly shows an upward trend in the hospital’s deficit, as the cost of healthcare began to rapidly increase following the war. MGH Annual Report for 1949. Designed by Linda Jackson

L-R: Alex Paterson, lawyer for the hospital; Claude Castonguay, the ‘father’ of Medicare; and Hon. G. Miller Hyde, founding president of the MGH Research Institute whose service to the MGH in various board positions spanned over forty years.

At the MGH’s 150th anniversary celebrations, 1971, with Alex Paterson, Claude Castonguay and Hon. G. Miller Hyde. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.202

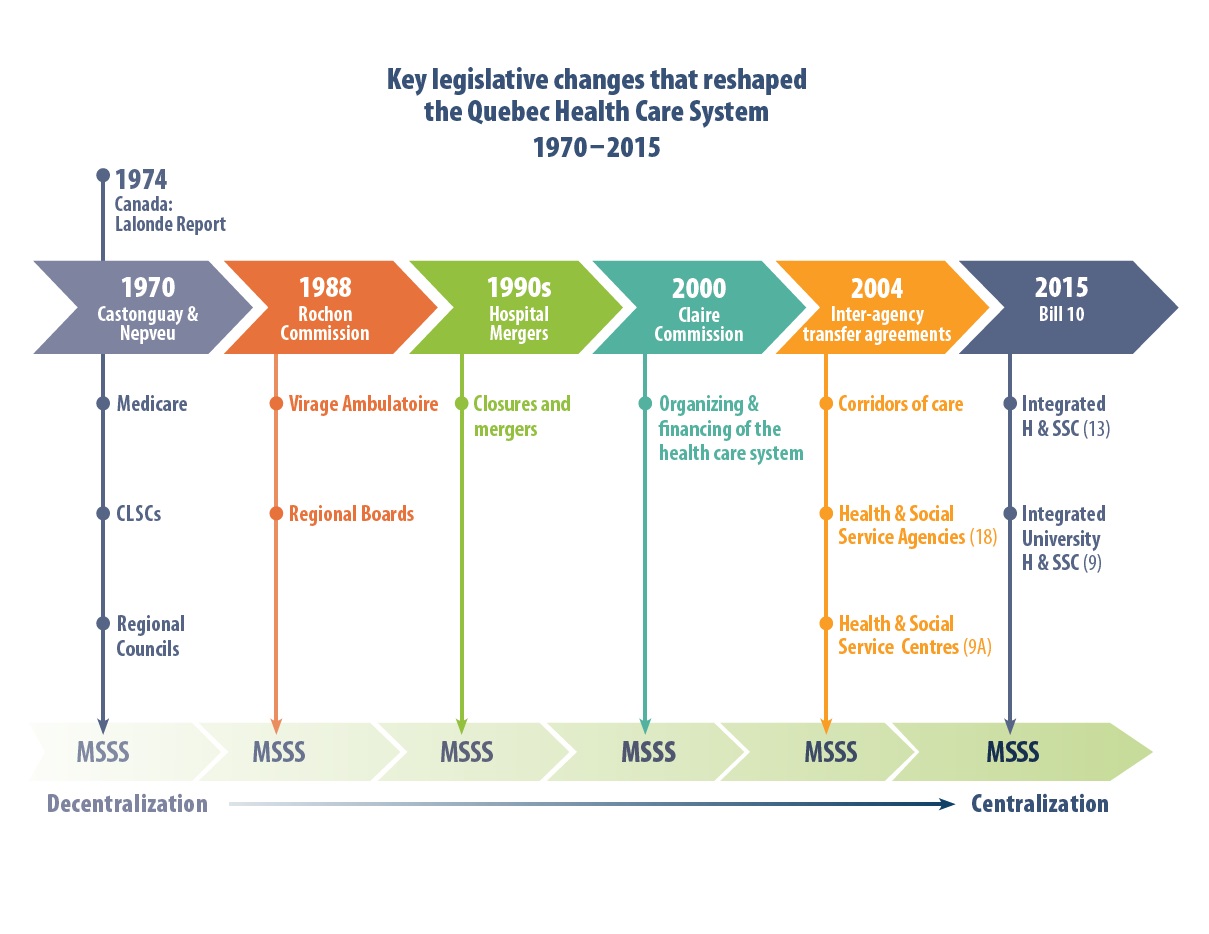

With the implementation of the Health Insurance Act in 1970, publicly funded healthcare was established in Quebec as a human right. Prior to this, the 1961 adoption of the Quebec Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act established a system whereby the province funded hospital-related costs for citizens through a cost-sharing program with the federal government. In 1967, the Castonguay-Nepveu Report called for sweeping changes in the administration of Quebec hospitals. These were implemented through Bill 8 (1970), which established the Medicare system, and Bill 65 (1971), through which the province took over management of healthcare, democratized hospital boards and committees, and set fees for specialty care.

With the establishment of Medicare, new programs within the hospital reflected a restructuring of society’s ideas of health. There was a new focus on legislating for patient empowerment, family and preventive healthcare, and population-based health, each of which had positive outcomes at the hospital. The patients’ rights movement emerged in the 1960s and was gradually recognized in law in Quebec in 1971 (after the Castonguay-Nepveu Report) and strengthened in 1991 (after the Rochon Commission).

Community Health

In 1974, as part of a decentralization process that saw increasing responsibility assigned to regional health boards, Quebec requested that the MGH establish a Department of Community Health (DSC) to develop a community-based healthcare program that addressed the needs of approximately 220,000 individuals in the greater Montreal area. This model also established CLSCs as the primary entry point into the provincial healthcare system.

DSCs oversaw collaboration between hospitals and other community institutions to address the health of the population. Rather than simply treating patients within its walls, the DSC ensured that the MGH was also engaged in public health and outreach programs such as home care, sexually transmitted disease prevention and education, perinatal programs, nutrition, gerontology, and mental health, to name a few.

Typical 3-trailer nursing station in Grise Fiord, Ellesmere Island, present-day Nunavut, 1970. Photo taken by Dr. Jane Forsey during an elective for her fourth year of medical school. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.850.8

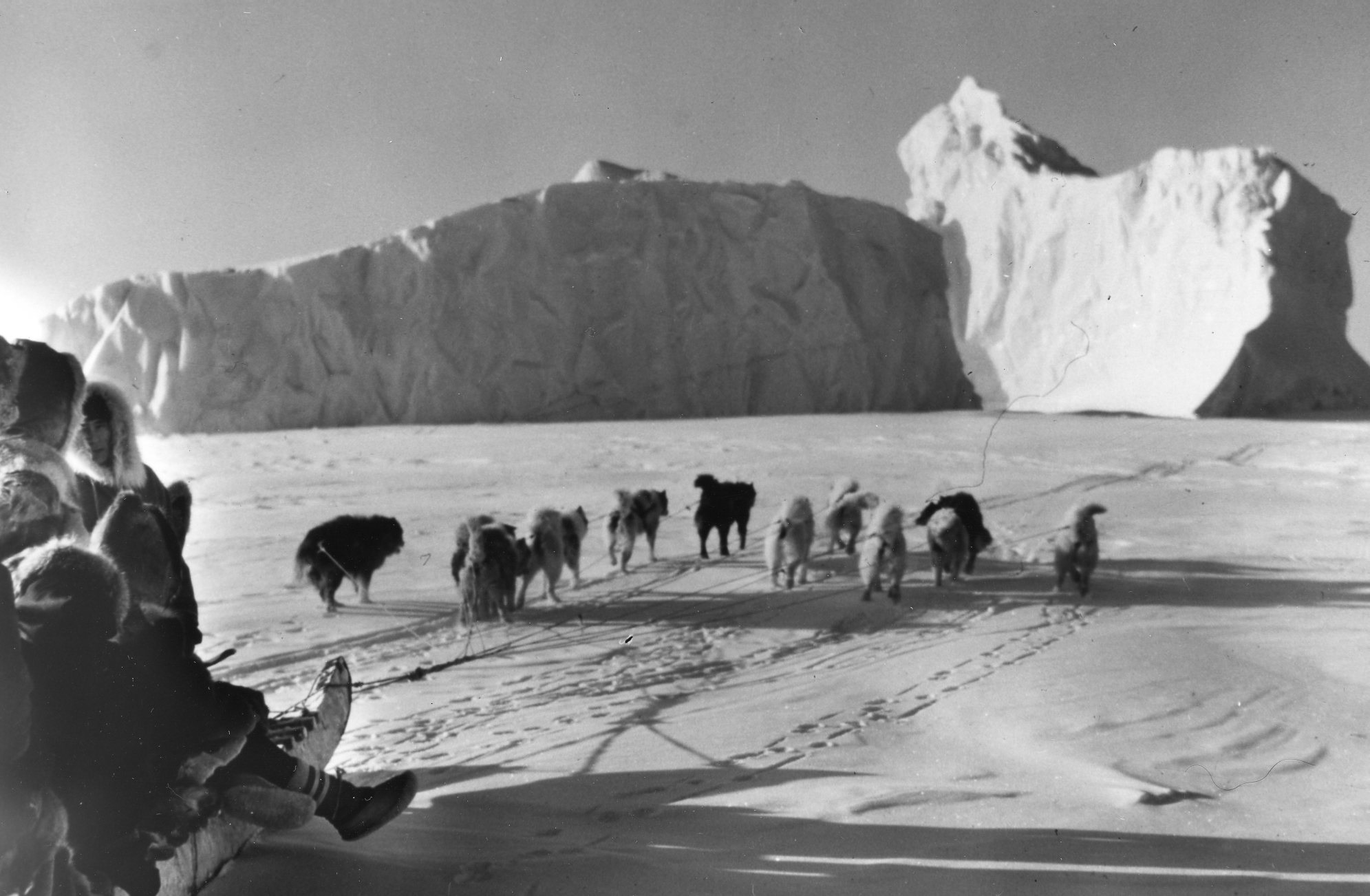

Burgess was first appointed consulting cardiologist for the McGill Baffin Project in 1973. Because of his experience, Burgess also became consulting cardiologist to Northern Quebec above the 55th parallel, later named Nunavik, where he served from 1992 until his retirement in 2003. The Northern Quebec arrangement was a less formal one between the hospitals in Puvirnituq and Kuujjuak. His responsibilities as cardiologist for Nunavut and Nunavik required one-week visits twice yearly to both regions, including visits to the larger nursing stations. He provided direct care and teaching sessions during his regular visits and corresponded from his office in Montreal. Burgess saw many changes in disease patterns and delivery of cardiac care over the course of his tenure as the Cree and Inuit adopted lifestyle patterns from the south, witnessing firsthand the appearance of coronary heart disease, hypertension and stroke.

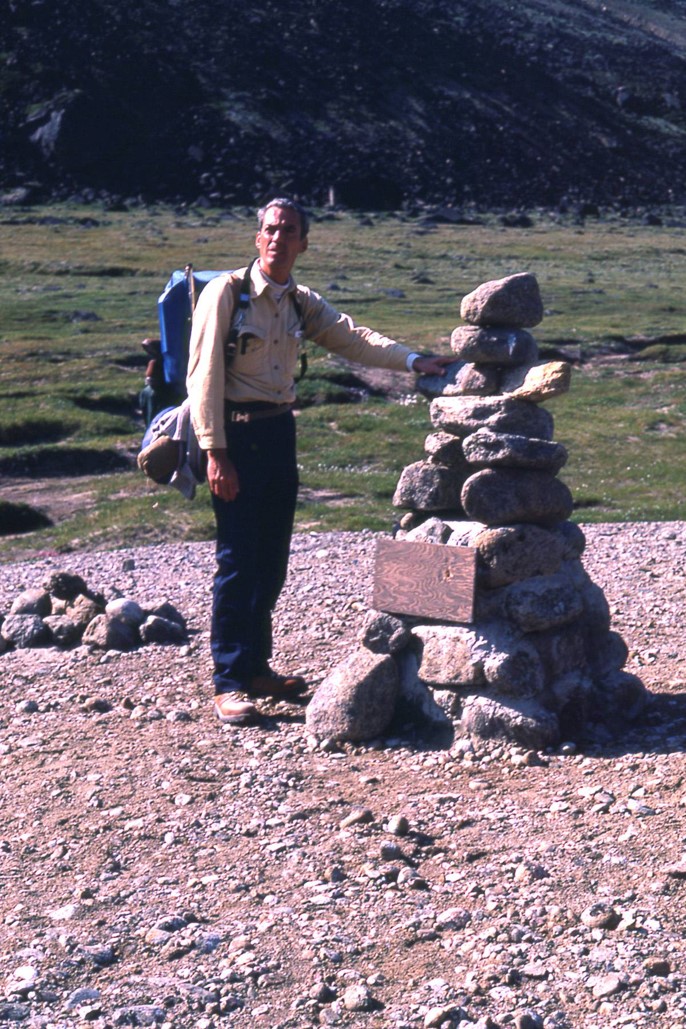

Dr. John H. Burgess at an inukshuk in the arctic circle, 1984. Burgess fell in love with Canada’s North, and published a book about his experiences (Doctor to the North: Thirty Years Treating Heart Disease Among the Inuit, 2008). Courtesy of Dr. John H. Burgess

The MGH’s role in community health fit neatly with its growing reputation for outreach programs. In 1973, at the behest of the Department of National Health and Welfare, Douglas Cameron agreed to establish an official liaison between McGill University and health services in present-day Nunavut, though the MGH had been sending doctors north on an ad-hoc basis as early as 1965. The program was terminated in 1998 when it was transferred to the University of Ottawa.

In 1978 the MGH agreed to operate the Northern Quebec Module, which made them responsible for the transport south and tertiary care of Cree and Inuit populations in Northern Quebec, and the transition of health services in the region to the Cree Board of Health and Social Services (CBHSS). This arrangement provided for the installation of a healthcare infrastructure in remote communities, and was part of treaty negotiations with the Quebec government. It also marked the earliest efforts at establishing a telehealth network, to mitigate harms related to Southern transfers.

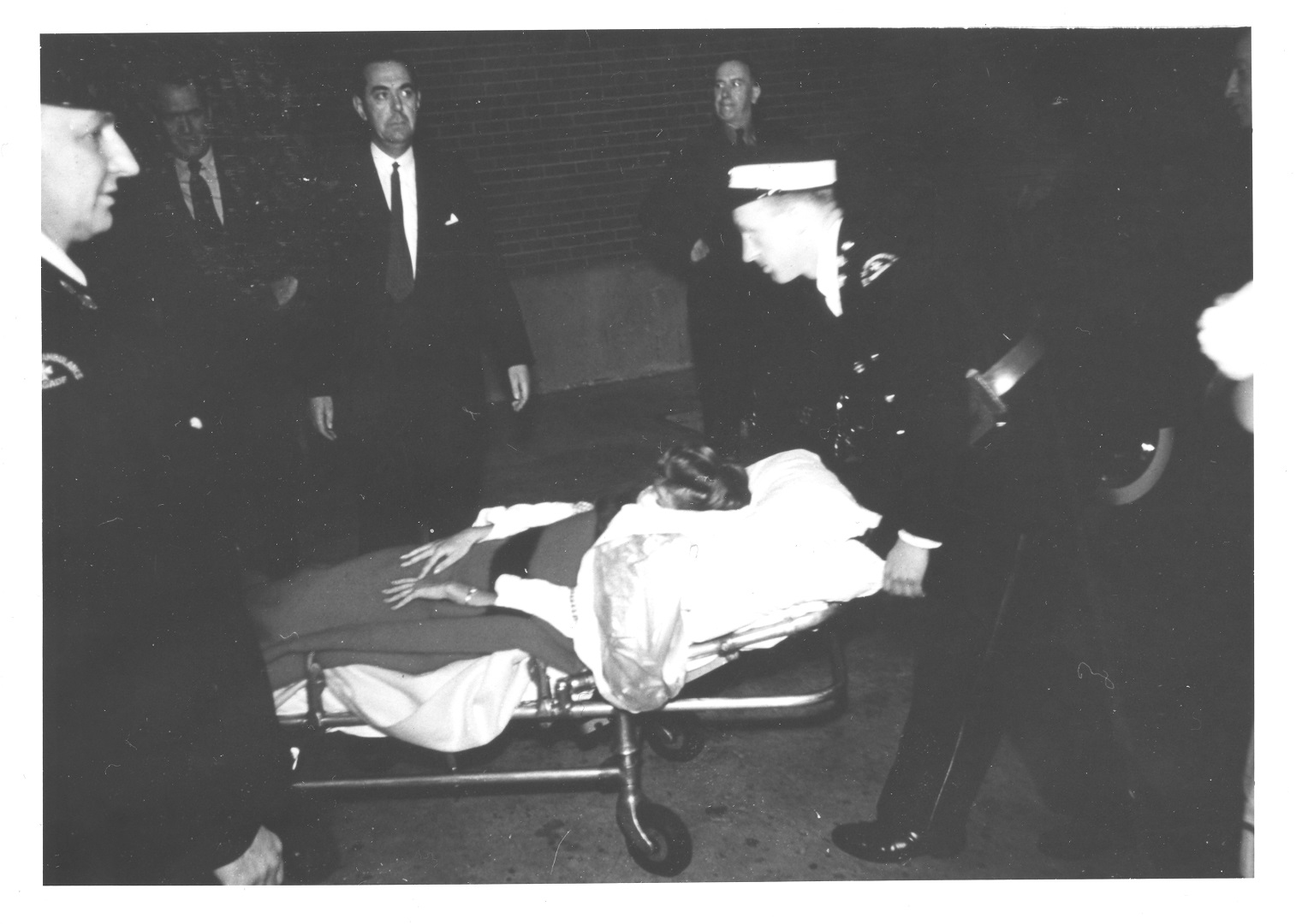

The MGH and Trauma Care

Dr. Rae Brown (centre) with a trauma patient in the surgical ICU, 1986. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.1007.3

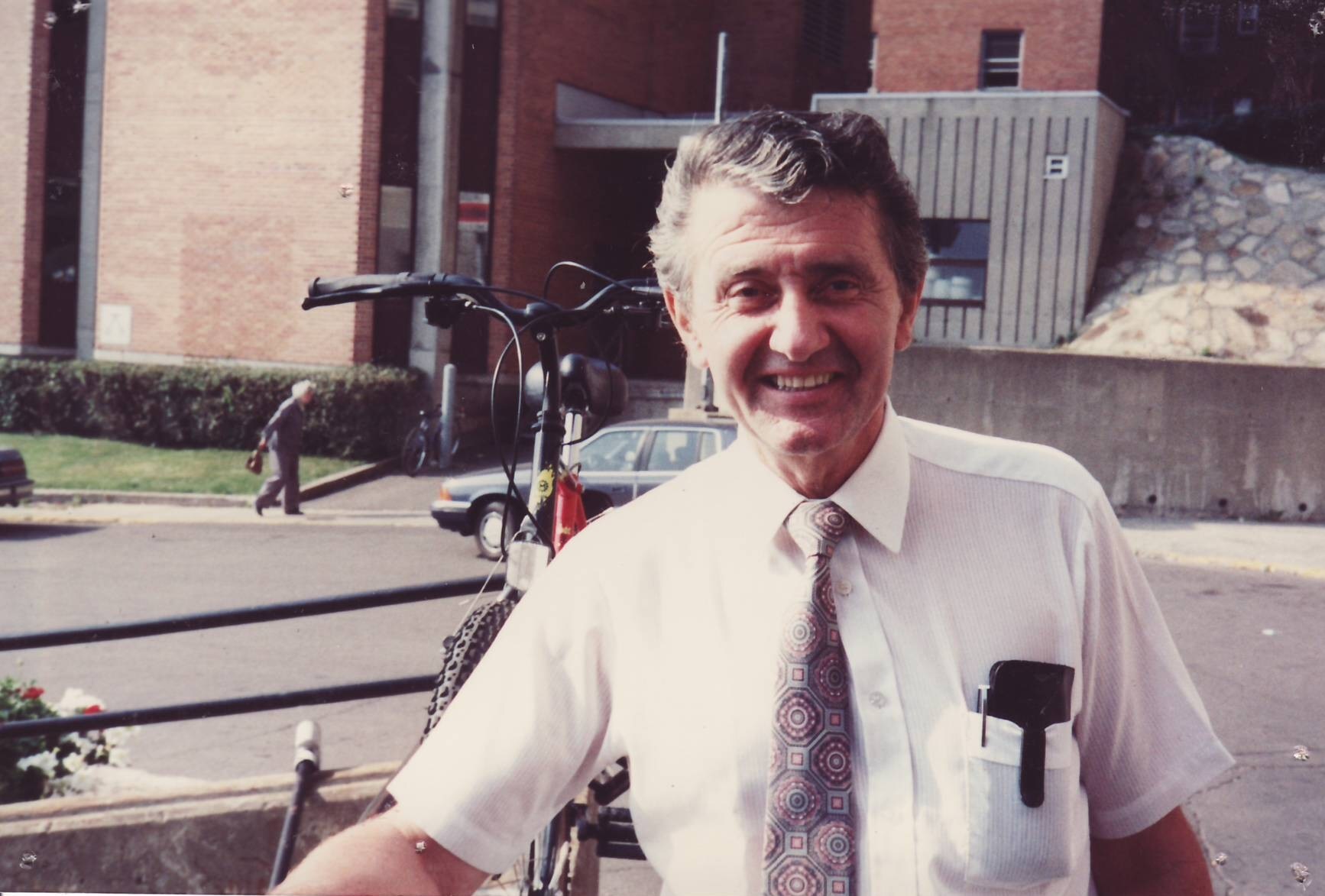

The MGH’s history of excellence in trauma care began with the war experiences of three of the hospital’s most renowned surgeons: Fraser B. Gurd, H. Rocke Robertson, and Fraser N. Gurd. Rocke Robertson established the hospital’s first trauma protocols during his short tenure as chief surgeon in the late fifties and early sixties based on his experiences commanding a field surgical unit in WWII.

The MGH’s city-wide reputation for its trauma service was well established by December 1989, when the mass shooting at L’Ecole Polytechnique happened. Trauma surgeons David Mulder and Rae Brown were on site when six victims arrived – within twenty minutes. All survived their injuries. A similar outcome occurred during the Dawson College shooting in 2007. Brown received the Trauma Achievement Award from the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons in 1991 for his work with the victims of the 1989 shooting.

Brown received the Trauma Award from the American College of Surgeons for his role in treating the victims of the Polytechnique Massacre, and Mulder helped establish the MGH as a Level 1 Trauma Centre for the province of Quebec.

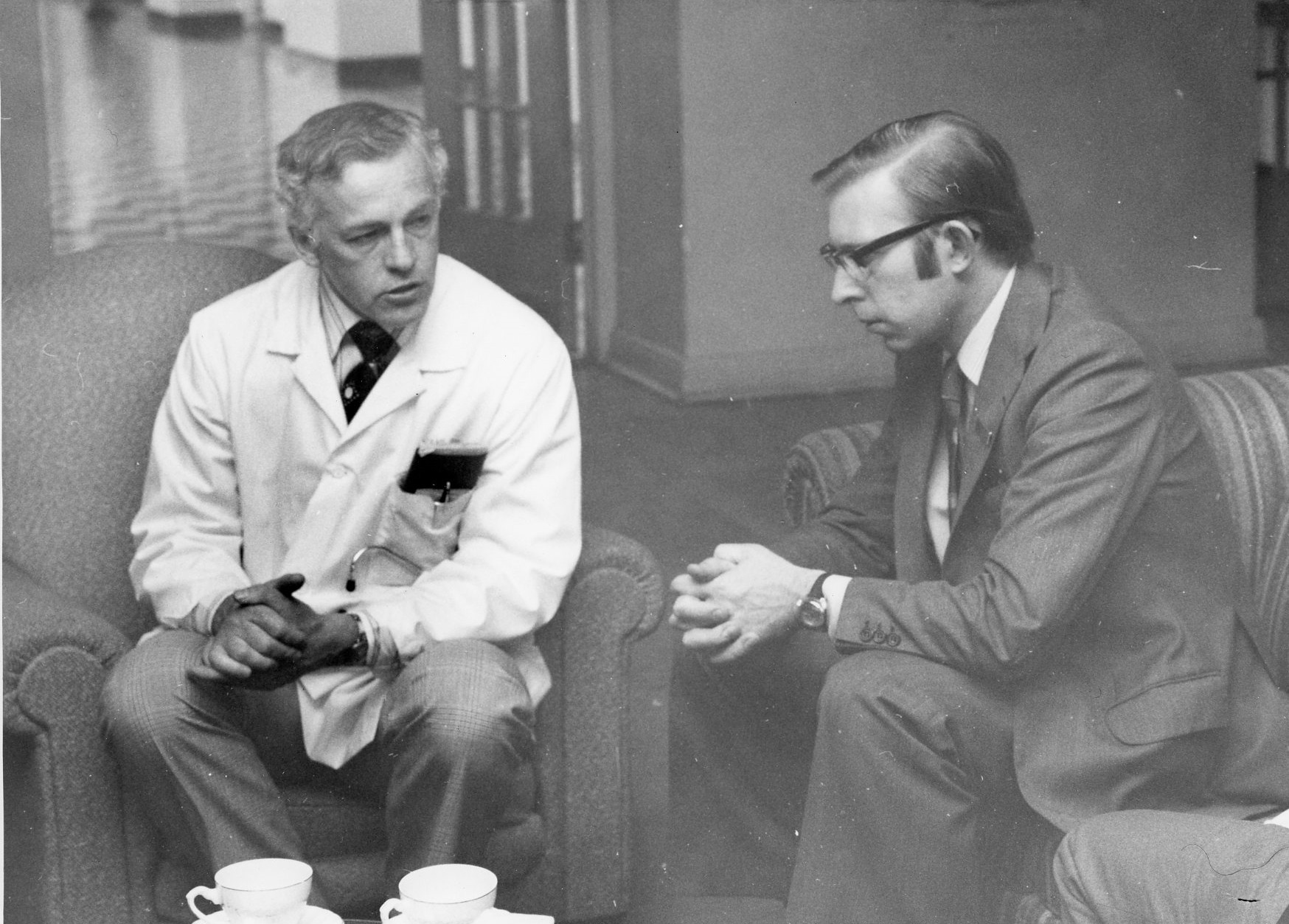

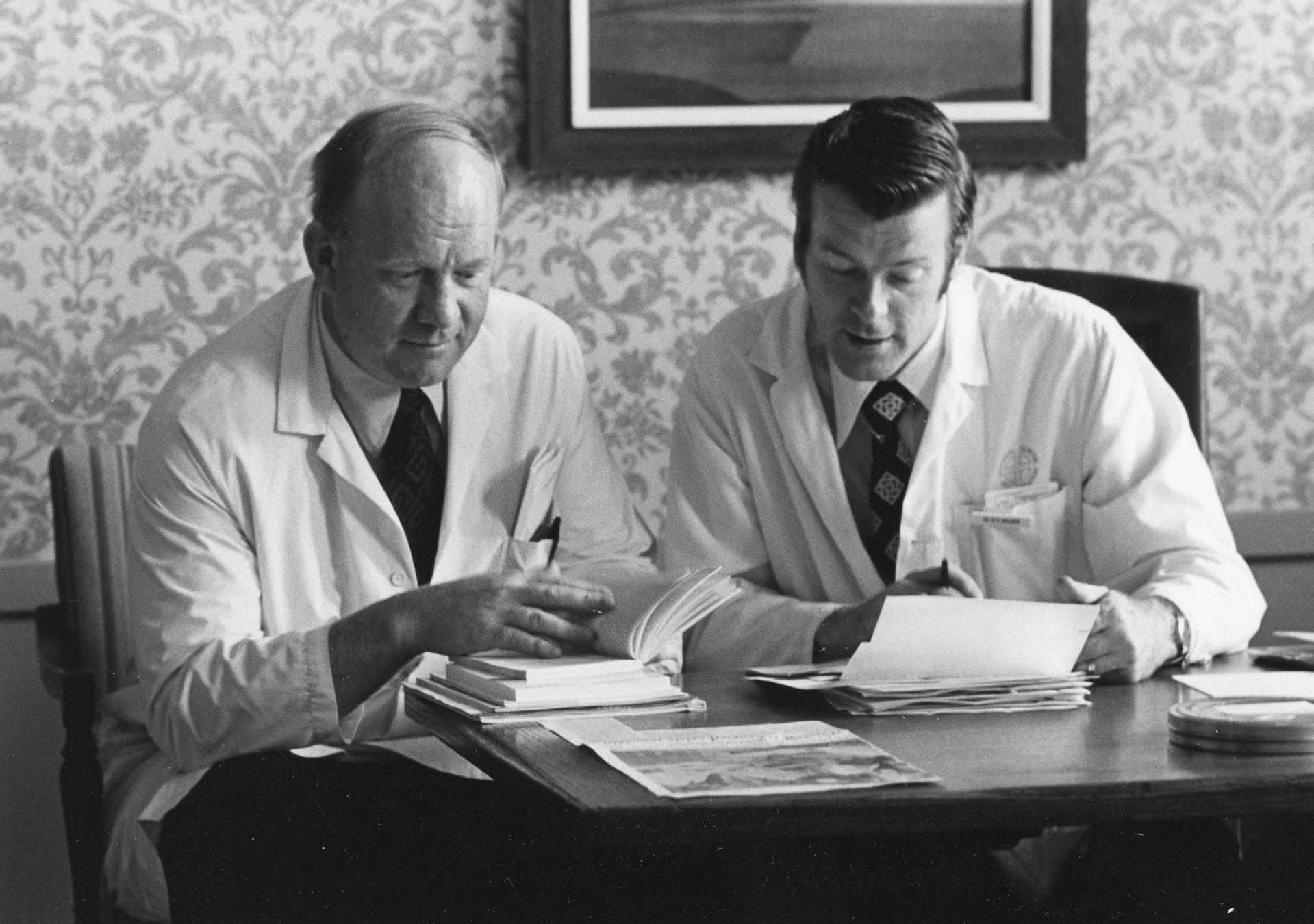

Drs. Rae Brown (left) and David Mulder, c. 1970. Art & Heritage Centre of the MUHC, Berkovitz Fonds, 2014-0014.04.682

In 1990, David Mulder led the consultancy of a task force appointed by Health Minister Marc Yvan Cote to look into increasing trauma-related death rates in Quebec, which had been as high as 51.8%. This led to the MGH being designated a level 1 trauma centre in 1993. Since 1992, the mortality rate associated with trauma has dropped drastically.